Stewart/Stuart & Sinclair

Scotland Royals

The nobility had special political and social status. Nobility is inherited or granted by the crown as a reward to persons who perform a heroic deed, have a notable achievement, or hold a prominent government position. British nobility has a well-defined order. The highest noblemen are peers, which include the titles (in descending rank) duke, marquis, earl, viscount, and baron. This is followed by the gentry, whose titles are baronet, knight, esquire, and gentleman. Both peers and gentry are entitled to bear coats of arms.

The noble class forms less than five percent of Scotland’s population. Scotland limited the growth of the noble class. The eldest son inherits the father’s title, and younger sons may or may not have lesser titles. When a nobleman dies without sons, the title lapses unless the crown awards the title to a daughter’s husband.

Most family traditions of having a noble ancestor are not true since most noblemen did not emigrate. Contrary to popular belief, few nobles were disowned by family members for unacceptable behavior. Thus, most traditions of an ancestor being "erased" or "eliminated" from all records are unfounded.

Illegitimate children were not entitled to noble status and are often not shown in family pedigrees. They may, however, have been granted a title and variation of the father’s coat of arms. Younger sons had the right to use the father’s coat of arms altered with cadency, a mark showing birth order. The records of peerage creations and related documents are kept at the Lyon Office (see Scotland Heraldry). There are many original records for noble families. These documents often are not available to the public, but you can accomplish most nobility research in secondary sources.

The noble class forms less than five percent of Scotland’s population. Scotland limited the growth of the noble class. The eldest son inherits the father’s title, and younger sons may or may not have lesser titles. When a nobleman dies without sons, the title lapses unless the crown awards the title to a daughter’s husband.

Most family traditions of having a noble ancestor are not true since most noblemen did not emigrate. Contrary to popular belief, few nobles were disowned by family members for unacceptable behavior. Thus, most traditions of an ancestor being "erased" or "eliminated" from all records are unfounded.

Illegitimate children were not entitled to noble status and are often not shown in family pedigrees. They may, however, have been granted a title and variation of the father’s coat of arms. Younger sons had the right to use the father’s coat of arms altered with cadency, a mark showing birth order. The records of peerage creations and related documents are kept at the Lyon Office (see Scotland Heraldry). There are many original records for noble families. These documents often are not available to the public, but you can accomplish most nobility research in secondary sources.

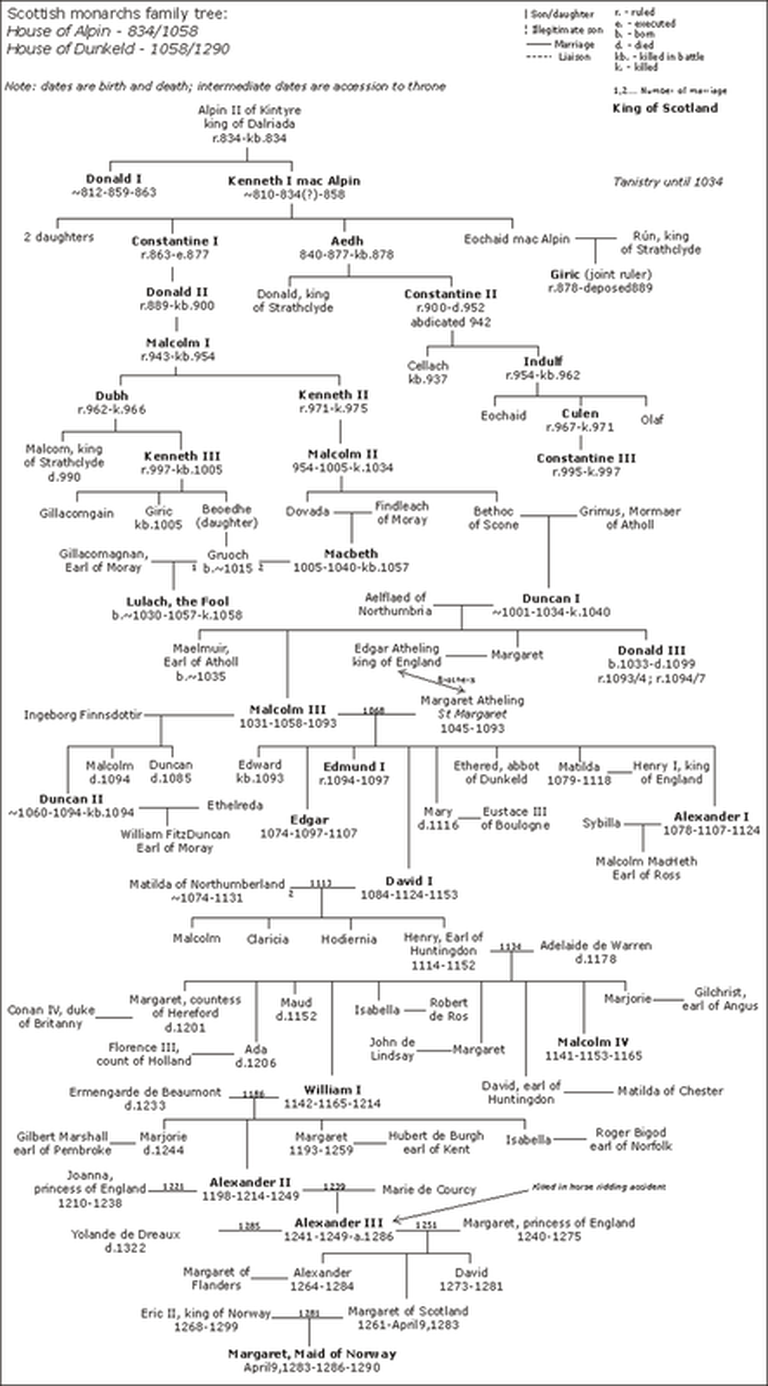

David I and his grandson Malcolm IV, Kings of Scotland - The Earliest Royal "Portraits" - National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh

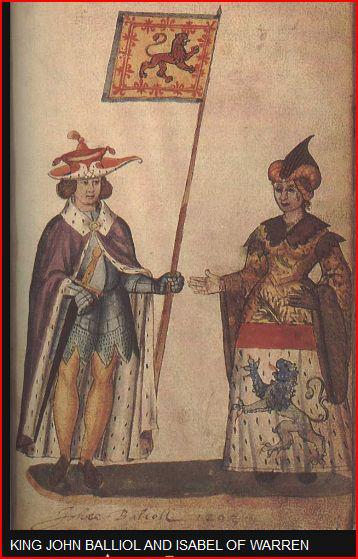

The rightful heir is not a Steward . He or she has to be descended from Alfred the Great, William de Normandie, Elizabeth Woodville, de la Zouche family, Hastings family, Plantagenet dynasty before Edward III Windsor, King Kenneth MacAlpine Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Not King Edward IV or any successor with Tudor exception .

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Society_of_Antiquaries_of_Scotland

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Society_of_Antiquaries_of_Scotland

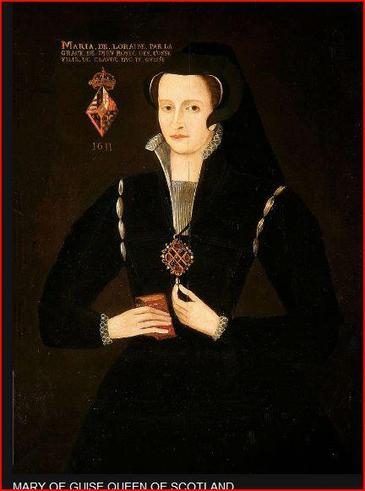

Mary Queen of Scots after Portrait by Zuccaro

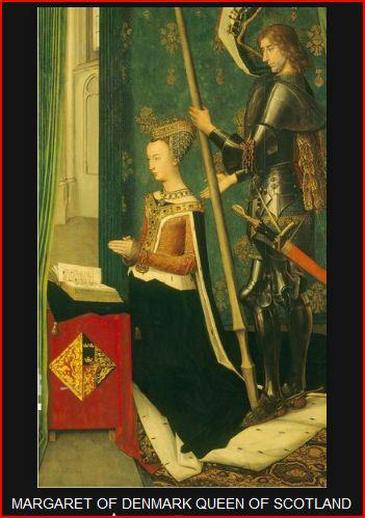

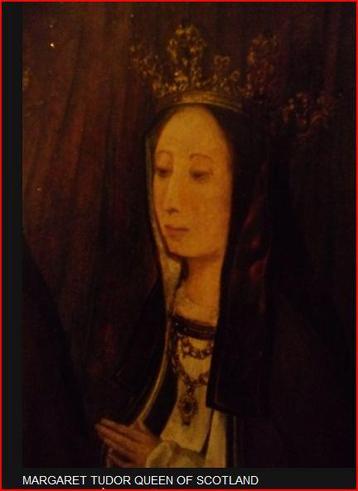

James V, Margaret of Denmark

Below: Allan Ramsay - Portrait of Queen Charlotte 1761-62

Below: Allan Ramsay - Portrait of Queen Charlotte 1761-62

N.C. Wyeth (The Scottish Chiefs)

Stewart CoA & Tartan

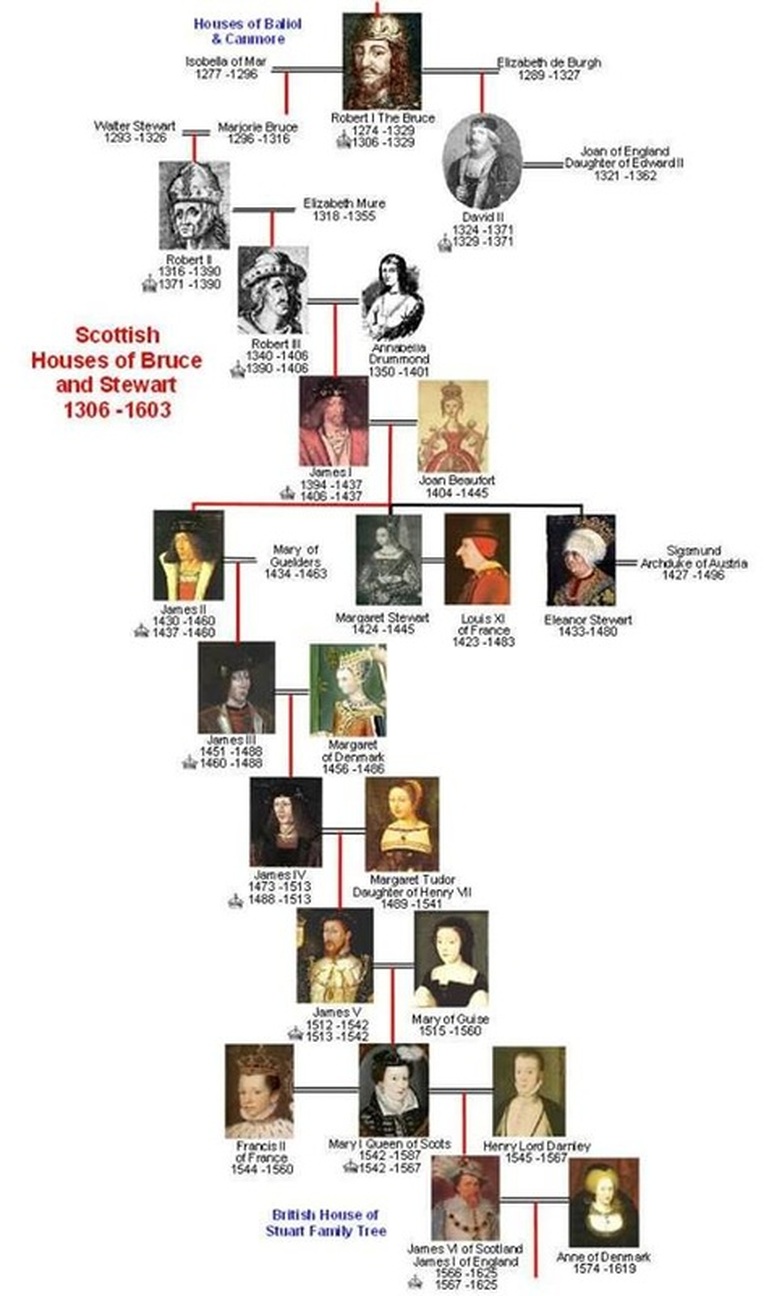

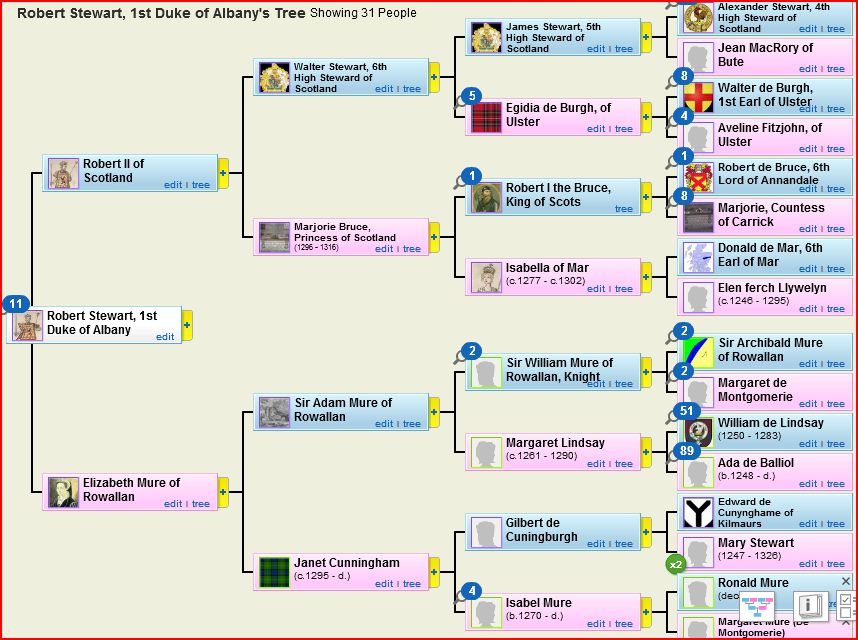

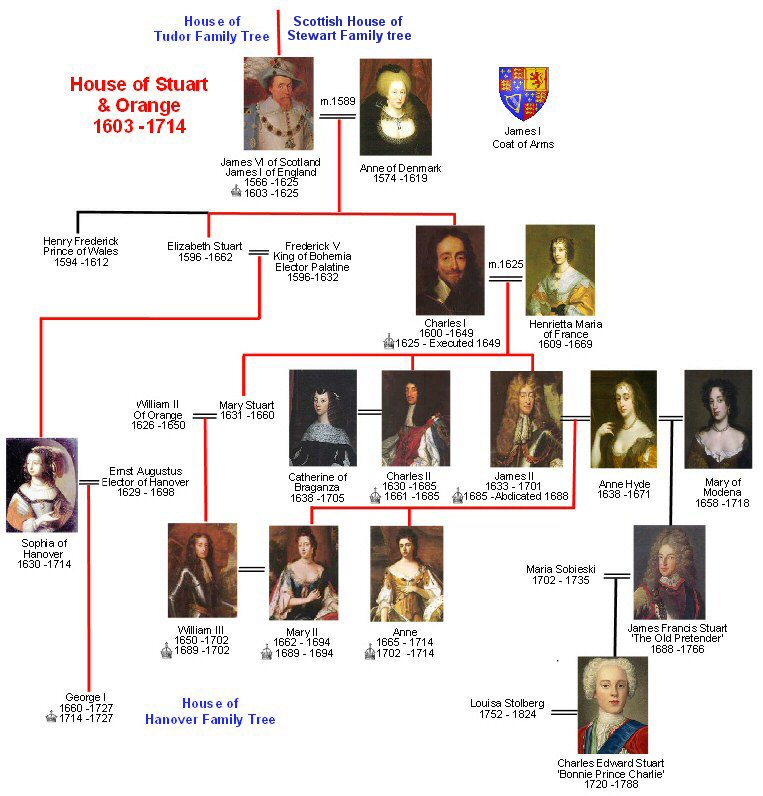

The Stuart Dynasty

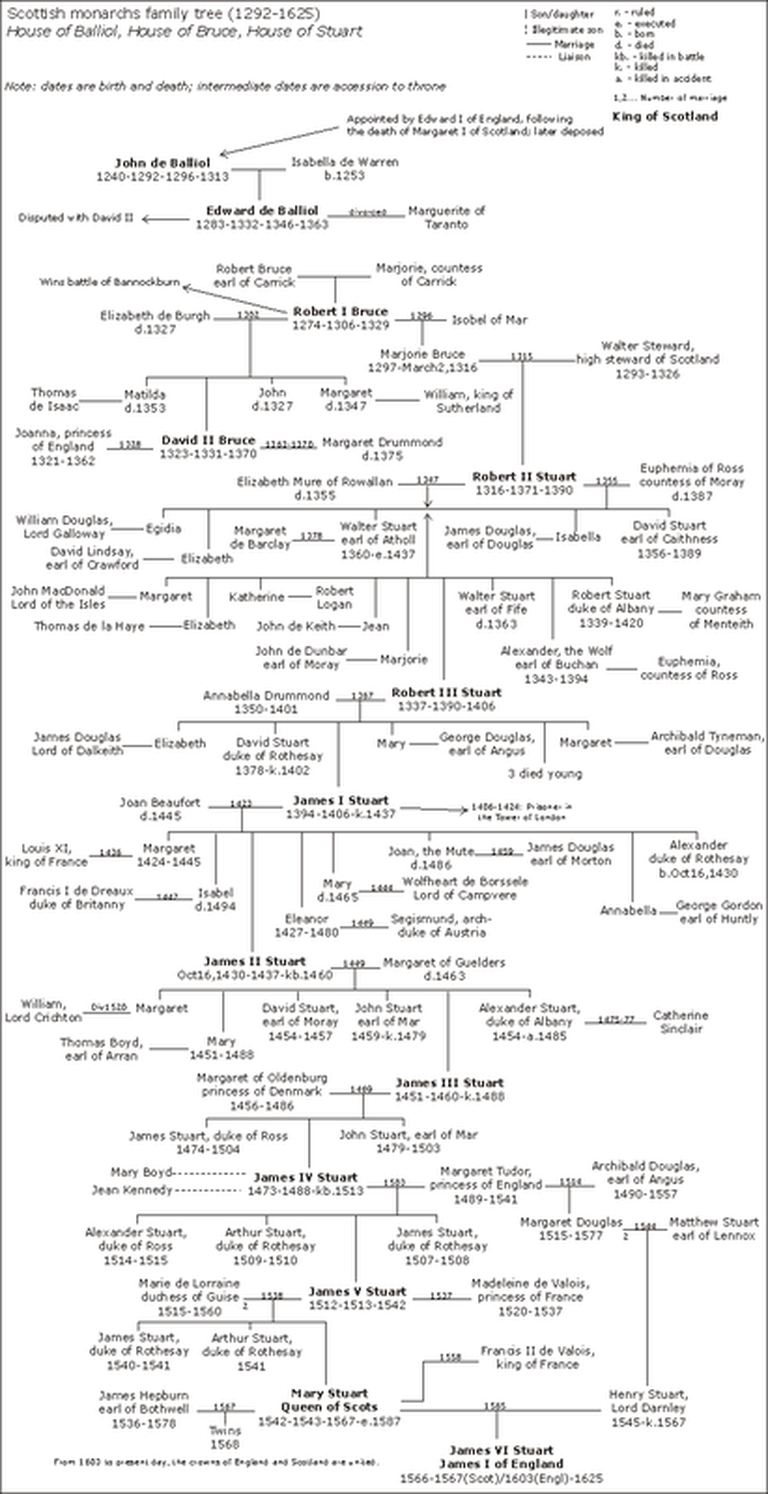

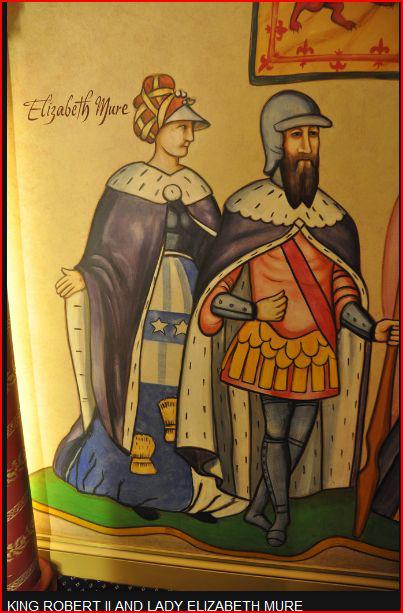

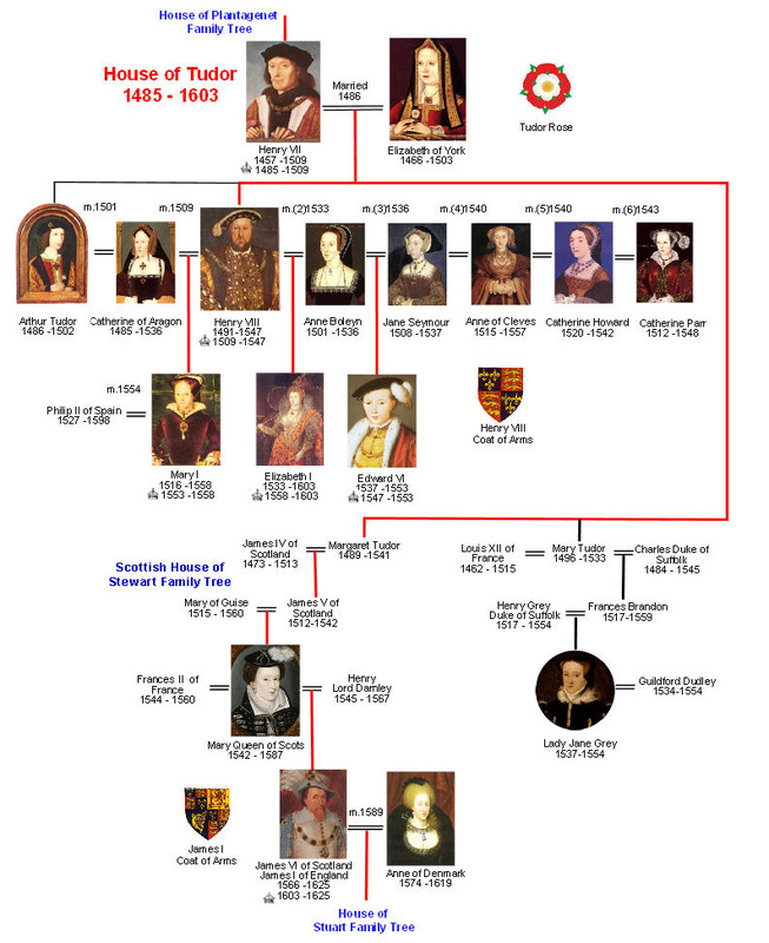

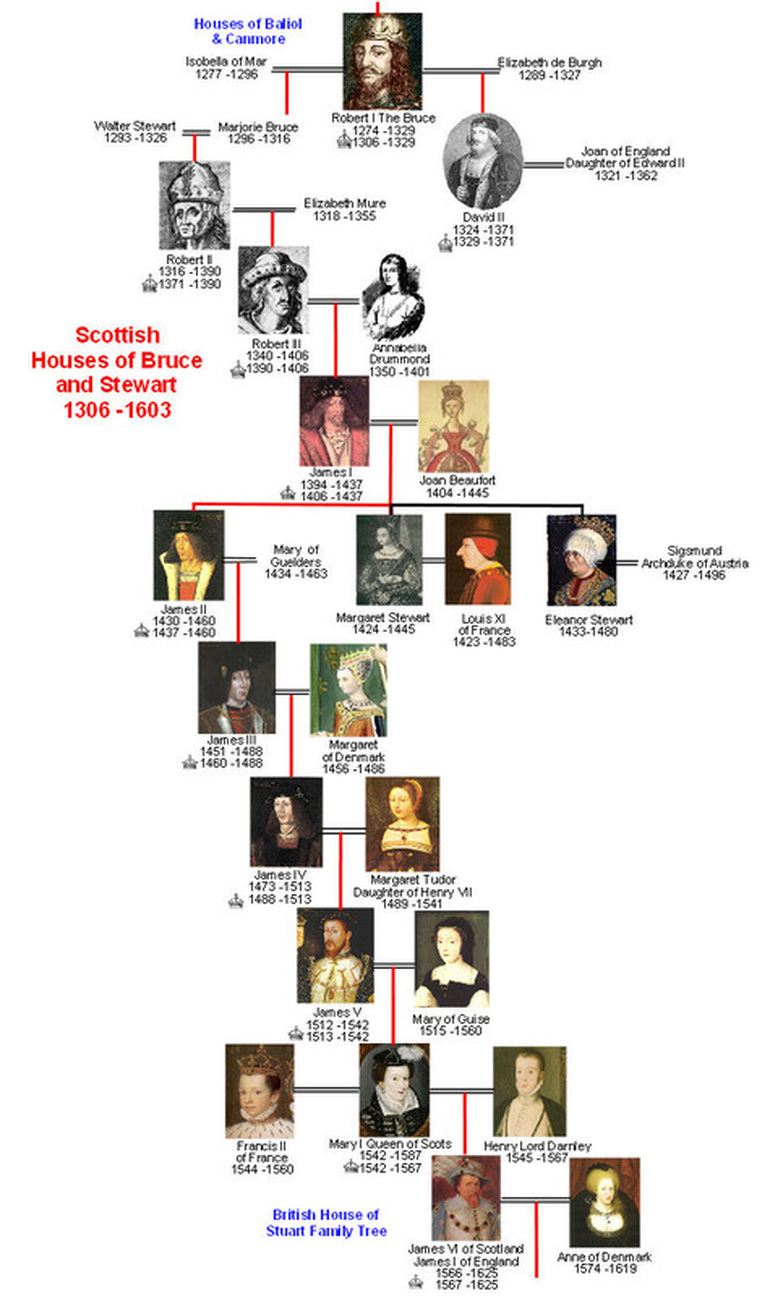

The Stuart dynasty began with Robert II taking the throne as King of Scots in 1371, and ended with the death of Anne of Great Britain in 1714.

In total, 15 monarchs ruled Scotland over 343 years. Five of these also ruled England, while Anne of Great Britain was the last Queen of Scots, the last Queen of England and the first monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

Stuart kings and queens with dates that they ruled Robert II of Scotland - 22 February 1371 to 19 April 1390

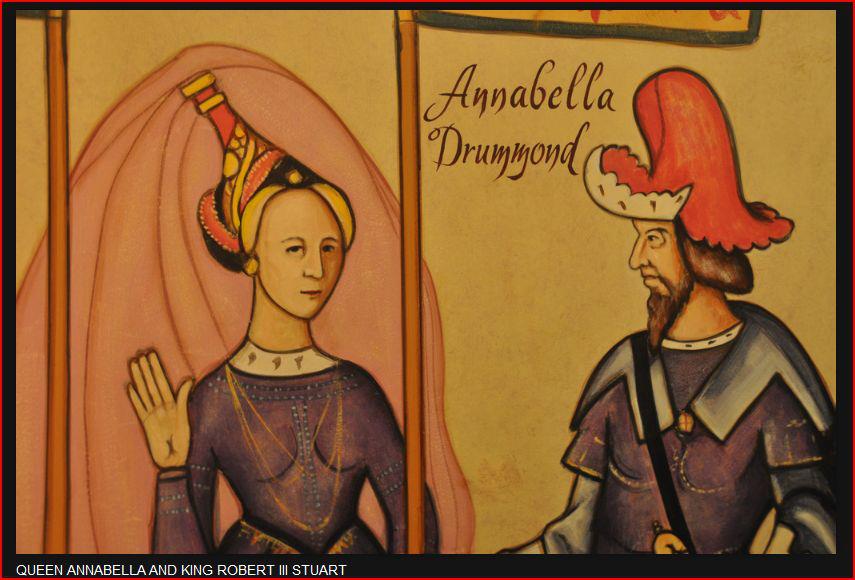

Robert III of Scotland - 19 April 1390 to 4 April 1406

James I of Scotland - 4 April 1406 to 21 February 1437

James II of Scotland - 21 February 1437 to 3 August 1460

James III - 3 August 1460 to 11 June 1488

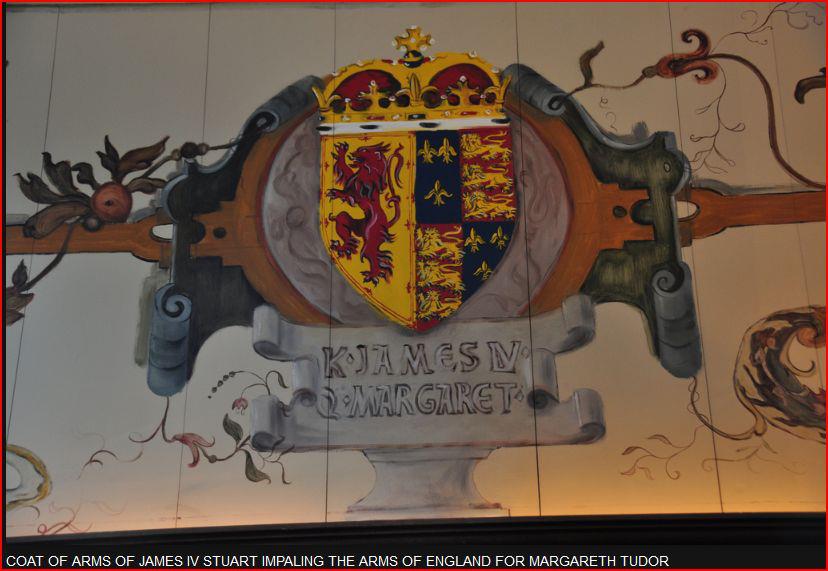

James IV - 11 June 1488 to 9 September 1513

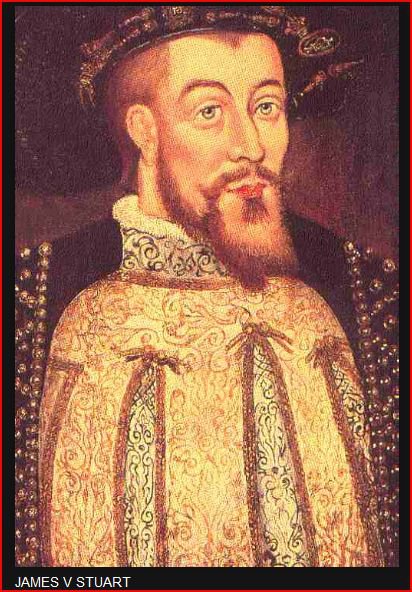

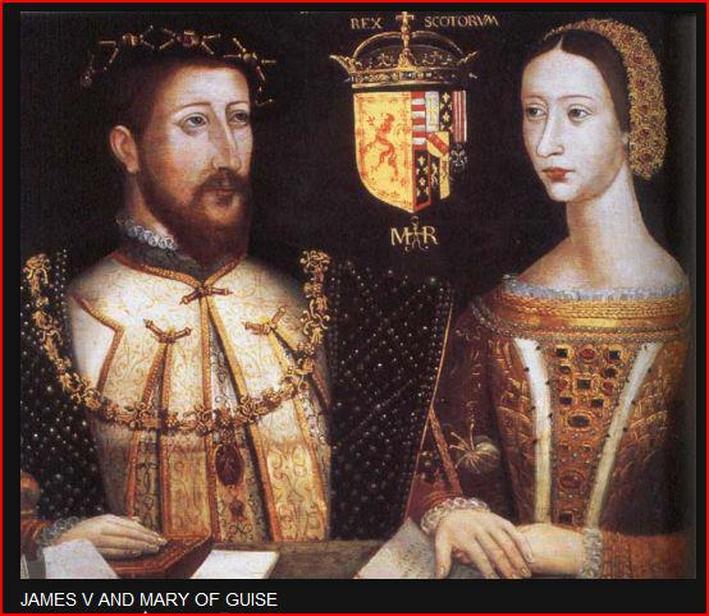

James V - 9 September 1513 to 14 December 1542

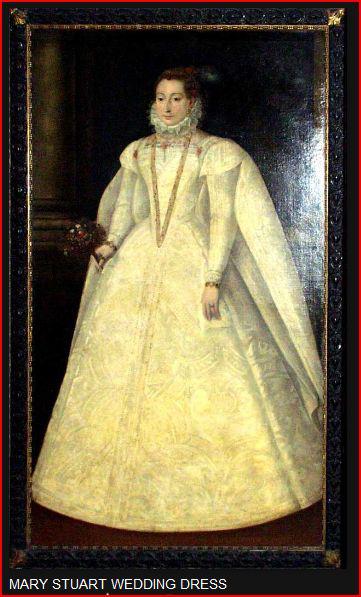

Mary Queen of Scots - 14 December 1542 to 24 July 1567

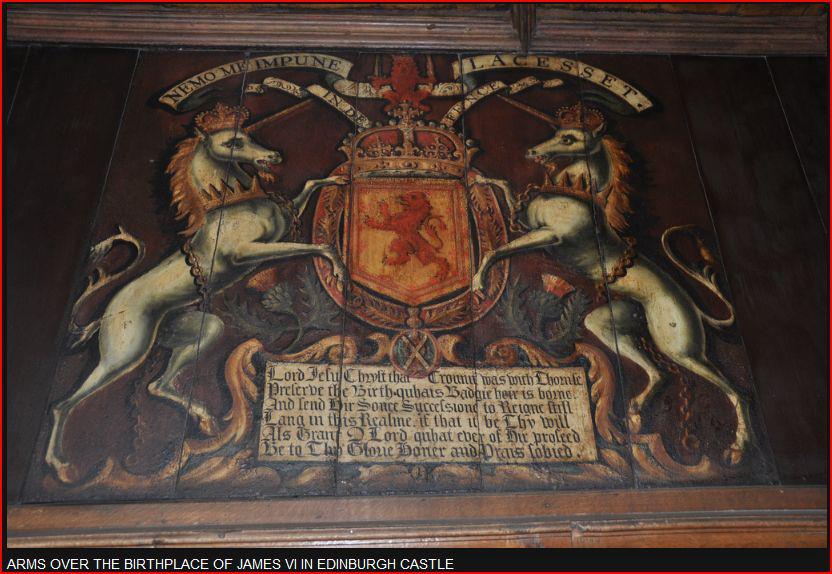

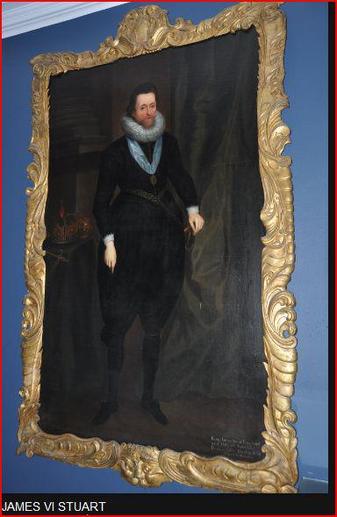

James VI of Scotland and I of England and Ireland - 24 July 1567 to 27 March 1625

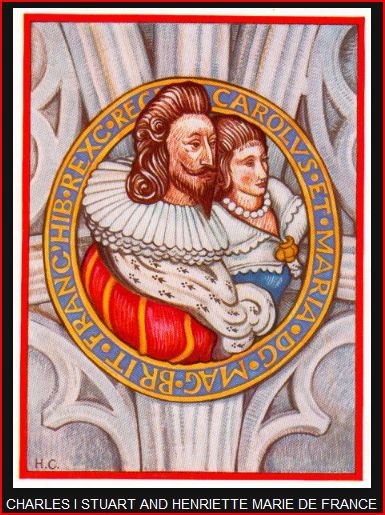

Charles I - 27 March 1625 to 30 January 1649

Charles II - 30 January 1649 to 6 February 1685

James VII of Scotland and II of England and Ireland - 6 February 1685 to 13 February 1689

Mary II - 13 February 1689 to 28 December 1694

Anne of Great Britain and Ireland - 8 March 1702 to 1 May 1707

The Stuart Dynasty

The Stuart dynasty began with Robert II taking the throne as King of Scots in 1371, and ended with the death of Anne of Great Britain in 1714.

In total, 15 monarchs ruled Scotland over 343 years. Five of these also ruled England, while Anne of Great Britain was the last Queen of Scots, the last Queen of England and the first monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

Stuart kings and queens with dates that they ruled Robert II of Scotland - 22 February 1371 to 19 April 1390

Robert III of Scotland - 19 April 1390 to 4 April 1406

James I of Scotland - 4 April 1406 to 21 February 1437

James II of Scotland - 21 February 1437 to 3 August 1460

James III - 3 August 1460 to 11 June 1488

James IV - 11 June 1488 to 9 September 1513

James V - 9 September 1513 to 14 December 1542

Mary Queen of Scots - 14 December 1542 to 24 July 1567

James VI of Scotland and I of England and Ireland - 24 July 1567 to 27 March 1625

Charles I - 27 March 1625 to 30 January 1649

Charles II - 30 January 1649 to 6 February 1685

James VII of Scotland and II of England and Ireland - 6 February 1685 to 13 February 1689

Mary II - 13 February 1689 to 28 December 1694

Anne of Great Britain and Ireland - 8 March 1702 to 1 May 1707

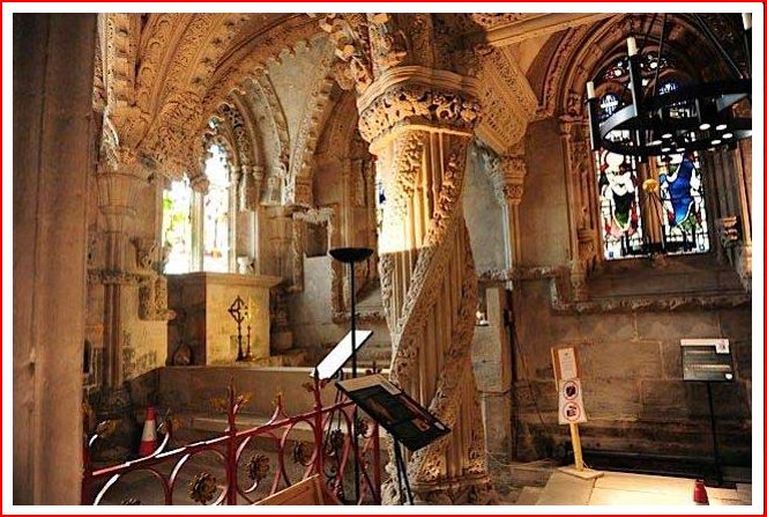

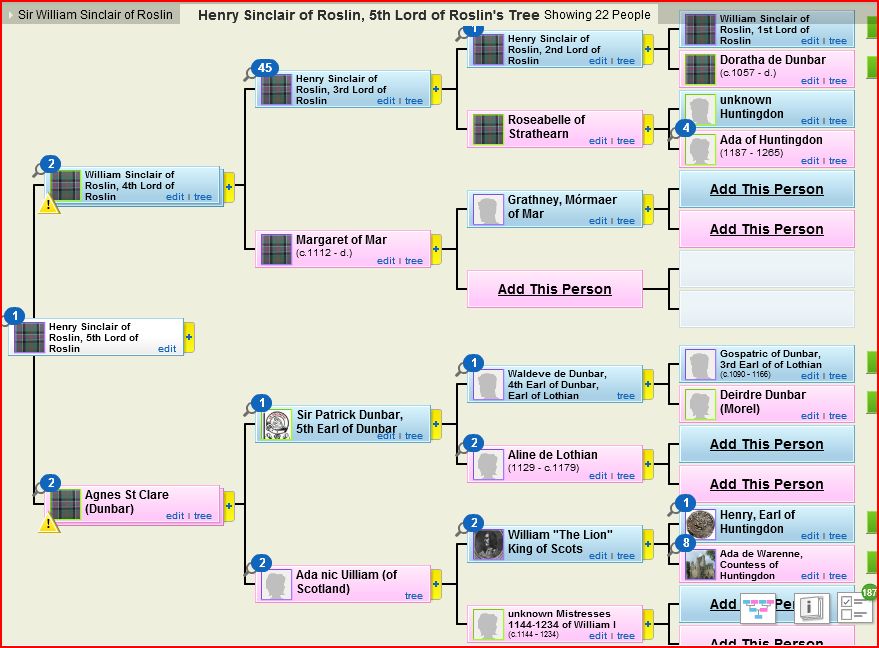

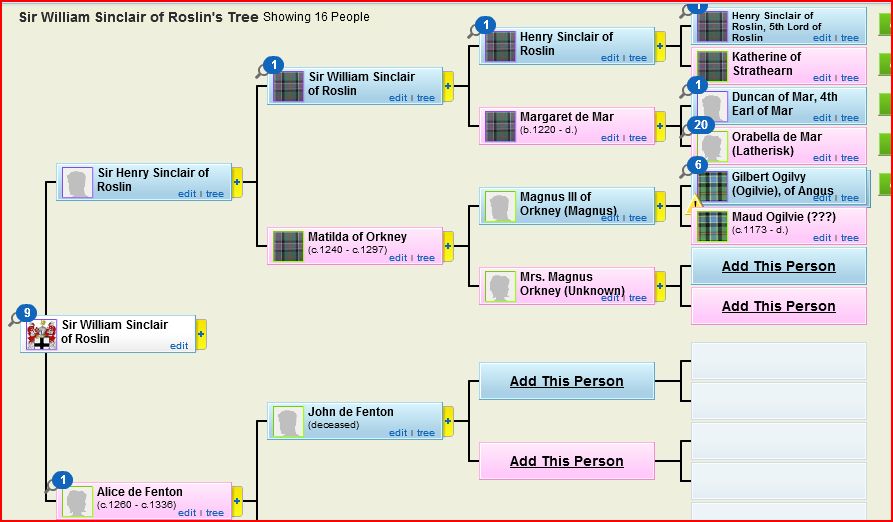

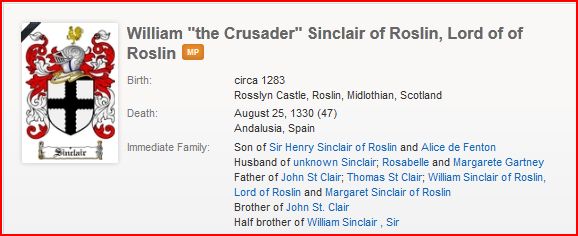

Sinclair Line & Rosslyn

photo Tina Gabriel

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosslyn_Chapel

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosslyn_Chapel

Double-portrait of William II (1626-1650), Prince of Orange, and his wife Mary Stuart (1631-1660).

Francis Theresa Stuart

Today, few people have heard of Henry Stuart (1594-1612) – eldest son of King James VI and I, older brother to the future Charles I. But back in 1612 things were very different. In fact, when, in November of that year, Henry’s life was ended by typhoid fever (he was just 18), the entire nation was plunged into grief. At Henry’s lavish funeral procession, 2,000 official mourners were joined by thousands lining the streets “whose streaming eyes made knowen howe much inwardly their harts did bleed”.

When it comes to burials, the Stuarts are pretty simple. Most of them are in vaults under the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey. Several of them had monuments planned but never executed, so most of them are commemorated by small stones in the Chapel's floor.

- James I and his queen Anne of Denmark are in vaults beneath the Henry VII Chapel.

- Charles I is in St. George's Chapel Windsor, in the Henry VIII vault (with Big Fat Hal himself, Jane Seymour and one of Queen Anne's babies); William IV put a rather nice memorial stone in the Chapel floor.

- Charles' queen, Henrietta Maria of France, was buried at the Saint Denis Basilica near Paris (with her father, Henri IV of France); her remains were thrown into a common grave after the mob raided the Bourbon vault in 1793.

- Charles II is in the Henry VII Chapel; a wax effigy stood over his grave for many years and is now in the Abbey museum.

- His queen Catherine of Braganza returned to Portugal after his death and is buried at the Jerónimos Monastery, in Belém, Lisbon.

- James II died in exile in France. He was buried in the Chapel of Saint Edmund in the Church of the English Benedictines in the Rue St. Jacques in Paris. In 1793, his tomb was set upon by the mob and his remains scattered. However, his viscera were buried near his place of death in the Parish Church of Saint-Germain-en-Laye; these were rediscovered in 1824 and reburied in the church. (I'm assuming the separation of the body was to do with preserving it while preparations for a state funeral were made; anyone want to correct me?)

- Lady Anne Hyde, James' first wife and the mother of the two queens who succeeded him, is buried in the Mary Queen of Scots vault in the Henry VII Chapel.

- Mary of Modena, James' second wife, was buried with him in Paris and also had her remains destroyed in 1793. Her viscera were reburied with his in 1824.

- Mary II and her husband and cousin William III are buried under the Henry VII chapel. A joint monument to them was planned but never executed, though wax effigies were made of them too, and can be seen in the Abbey museum. Mary's spectacular funeral cost £50,000

- Mary's sister, Queen Anne, and her husband Prince George of Denmark and Norway, Duke of Cumberland, are buried under the Henry VII Chapel. Anne's body was so obese and swollen by gout that it apparently had to be carried in a coffin that was almost square.

- James II's son, James Francis Edward, Prince of Wales, a.k.a. James III, a.k.a. The Old Pretender, died in Rome and was buried in the crypt of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican.

- His son, Prince Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Maria Stuart, a.k.a. Bonnie Prince Charlie, a.k.a. the Young Pretender, was initially buried in the Cathedral of Frascati where his brother was bishop. After his brother's death, his remains were moved to St. Peter's Basilica, though his heart was left in an urn in Frascati.

Who are the Scots-Irish Americans? Many Americans of Celtic descent also mistakenly believe they are Irish when in fact they are Scots-Irish. Scots-Irish Americans are descendants of Scots who lived in Northern Ireland for two or three generations but retained their Scottish character and Protestant religion. Scots went to Northern Ireland beginning when the Scottish Stewarts took over the throne of England, just after 1601 The late Elizabeth I of England had just defeated and driven out the duplicitous Earls of Ulster and between that war and the warfare between the earls themselves just before they joined to renege upon their English treaties, the land had become largely unpopulated. James I, decided that to prevent other troublesome Irish from moving into the area, he would create new colonies for Protestant Scots and English. Not many English wanted the poorer lands of Ulster. Scots did because improvements in agriculture, livestock, and crafts and commerce had led to a population explosion in Scotland after 1513, and the people were literally running out of useable land. Thus Ulster by 1640 was inhabited by a Scottish majority--and by 1700 had literally hundreds of thousands of Scots families living there. However, their descendants are mostly unaware of how northern Ireland came to be settled and dominated by Scots between 1600 and 1700. They know only perhaps that grandpa`s or grandma`s family Bible shows they came to America from Ireland, or that there's an importation record in an eastern seaboard state that says they arrived from Ireland in such year, and they believe they are simply Irish.

The earliest large group of Scots-Irish mixed with Scots emigrated because they were Presbyterians being persecuted by Charles I. They did not want bishops and would not take loyalty oaths to the Church of England/Scotland in exchange for recognition of their ministers. The Puritans, English Congregationalists who dominated Massachusetts then invited the Scots-Irish and Scots Presbyterian "dissenters" to settle among them. Scots-Irish and Scots dissenters then were arriving by the multiple ship-loads in Massachusetts by the 1640's. However, the Massachusetts Congregationalists soon began complaining about the less modest dress of Scottish/Scots-Irish women and the freer, less disciplined Scottish children. They also did not agree with the Scots insistence on educating all their children, girls as well as boys, to read write and do arithmetic, and to allow women to be elders of the church congregations. Soon Massachusetts was settling Scots-Irish and Scots emigrants on its most dangerous frontiers and requiring double tithes of the Scottish Presbyterian communities where there were both Presbyterian and Congregationalist churches. By the late 1600's Scots-Irish and Scots were being clearly treated as less desireable second class citizens in Massachusetts and they were no longer emigrating in large numbers to Massachusetts. Many later Scots-Irish and Scots who already had relatives in Massachusetts were emigrating to New York, and settling along the New York frontier with the Iroquois, or in safer New Jersey. Also, eventually the split between the Scots and Scots-Irish Presbyterians and the English Congregationalists in Massachusetts led to the development of the separate colonies/states of more Scottish New Hampshire and Vermont. The next large group of Scots-Irish combined with Scots first arrived in Virginia also as a result of persecution by Charles I in the 1640's. However, many more Scots-Irish and Scots then arrived between 1649 and 1660, because they and the Commonwealth of Virginia were loyalists to the Stewarts, and against Cromwell. They settled in Virginia and Maryland, which, as a Catholic colony, and so loyal to the Stewarts, welcomed them. The next group settled in Maryland in the 1670's-80's, on the eastern peninsula, including what became Delaware, which was not its own separate colony until the 1770's.

Then came the largest of all of the early Scots-Irish and Scots waves of emigration between 1713-1746. This was when the Scottish Stewarts were replaced by the German Hanovers as the ruling family of England and Scotland. The Scots no longer enjoyed as much attention, favor and commercial privileges under the Hanovers. Worse, after the Act of Union became fully implemented, Ulster found itself left out and had none of the commercial privileges enjoyed by Scotland itself. Ulster was not permitted international trade, only trade with England and Scotland, causing a collapse in the economy. At the same time the landlords were allowed, in violation of previous Stewart mandates and restrictions, to drastically raise rents on lands that were supposed to have been sold to plantation tenants but never were. The resulting group of hundreds of thousands of Scots-Irish and Scots emigrants, primarily arrived through what had become the Pennsylvania port of Newcastle, the main port of Philadelphia itself. The group mostly settled initially in the Maryland counties closest to existing Pennsylvania counties, and in Chester and Lancaster counties in Pennsylvania and the counties that became Delaware.

However, Pennsylvania was slow to sell or grant lands to the new emigrants and Virginia decided to welcome them instead in the 1730's. The result was that more than half of the Scots-Irish and Scottish families who first tried to settle in Pennsylvania went south from the Potomac through the Shenandoah Valley into Virginia and settled the Piedmont, Great Valley, adjacent valleys, and the eastern parts of the Blue Ridge in Virginia, Maryland and North Carolina. Some of the post 1713 Scots-Irish and Scots who had arrived at Newcastle, also went to Baltimore, along with Maryland descendants of earlier generations of Scots-Irish and Scots. These groups together built up Baltimore as a major commercial port city, like Glasgow back in Scotland, which became a major trading partner.

By the time of the Revolution, one more significant group had arrived in North and South Carolina after the defeat of the Scots and Scots-Irish trying to restore the Stewarts at Culloden and the subsequent massacres of Scots by the Hanoverian Duke of Cumberland. Just before the American Revolution, in 1771-3,a rebellion of mostly Scots-Irish in North Carolina, against English landlords called "The Regulators Rebellion" resulted in severe punishment by Governor Tryon and many Scots-Irish and Scottish families then fleeing to South Carolina, where they settled in the old Spartanburg and Ninety-six Districts.

The earliest large group of Scots-Irish mixed with Scots emigrated because they were Presbyterians being persecuted by Charles I. They did not want bishops and would not take loyalty oaths to the Church of England/Scotland in exchange for recognition of their ministers. The Puritans, English Congregationalists who dominated Massachusetts then invited the Scots-Irish and Scots Presbyterian "dissenters" to settle among them. Scots-Irish and Scots dissenters then were arriving by the multiple ship-loads in Massachusetts by the 1640's. However, the Massachusetts Congregationalists soon began complaining about the less modest dress of Scottish/Scots-Irish women and the freer, less disciplined Scottish children. They also did not agree with the Scots insistence on educating all their children, girls as well as boys, to read write and do arithmetic, and to allow women to be elders of the church congregations. Soon Massachusetts was settling Scots-Irish and Scots emigrants on its most dangerous frontiers and requiring double tithes of the Scottish Presbyterian communities where there were both Presbyterian and Congregationalist churches. By the late 1600's Scots-Irish and Scots were being clearly treated as less desireable second class citizens in Massachusetts and they were no longer emigrating in large numbers to Massachusetts. Many later Scots-Irish and Scots who already had relatives in Massachusetts were emigrating to New York, and settling along the New York frontier with the Iroquois, or in safer New Jersey. Also, eventually the split between the Scots and Scots-Irish Presbyterians and the English Congregationalists in Massachusetts led to the development of the separate colonies/states of more Scottish New Hampshire and Vermont. The next large group of Scots-Irish combined with Scots first arrived in Virginia also as a result of persecution by Charles I in the 1640's. However, many more Scots-Irish and Scots then arrived between 1649 and 1660, because they and the Commonwealth of Virginia were loyalists to the Stewarts, and against Cromwell. They settled in Virginia and Maryland, which, as a Catholic colony, and so loyal to the Stewarts, welcomed them. The next group settled in Maryland in the 1670's-80's, on the eastern peninsula, including what became Delaware, which was not its own separate colony until the 1770's.

Then came the largest of all of the early Scots-Irish and Scots waves of emigration between 1713-1746. This was when the Scottish Stewarts were replaced by the German Hanovers as the ruling family of England and Scotland. The Scots no longer enjoyed as much attention, favor and commercial privileges under the Hanovers. Worse, after the Act of Union became fully implemented, Ulster found itself left out and had none of the commercial privileges enjoyed by Scotland itself. Ulster was not permitted international trade, only trade with England and Scotland, causing a collapse in the economy. At the same time the landlords were allowed, in violation of previous Stewart mandates and restrictions, to drastically raise rents on lands that were supposed to have been sold to plantation tenants but never were. The resulting group of hundreds of thousands of Scots-Irish and Scots emigrants, primarily arrived through what had become the Pennsylvania port of Newcastle, the main port of Philadelphia itself. The group mostly settled initially in the Maryland counties closest to existing Pennsylvania counties, and in Chester and Lancaster counties in Pennsylvania and the counties that became Delaware.

However, Pennsylvania was slow to sell or grant lands to the new emigrants and Virginia decided to welcome them instead in the 1730's. The result was that more than half of the Scots-Irish and Scottish families who first tried to settle in Pennsylvania went south from the Potomac through the Shenandoah Valley into Virginia and settled the Piedmont, Great Valley, adjacent valleys, and the eastern parts of the Blue Ridge in Virginia, Maryland and North Carolina. Some of the post 1713 Scots-Irish and Scots who had arrived at Newcastle, also went to Baltimore, along with Maryland descendants of earlier generations of Scots-Irish and Scots. These groups together built up Baltimore as a major commercial port city, like Glasgow back in Scotland, which became a major trading partner.

By the time of the Revolution, one more significant group had arrived in North and South Carolina after the defeat of the Scots and Scots-Irish trying to restore the Stewarts at Culloden and the subsequent massacres of Scots by the Hanoverian Duke of Cumberland. Just before the American Revolution, in 1771-3,a rebellion of mostly Scots-Irish in North Carolina, against English landlords called "The Regulators Rebellion" resulted in severe punishment by Governor Tryon and many Scots-Irish and Scottish families then fleeing to South Carolina, where they settled in the old Spartanburg and Ninety-six Districts.

THE PEERAGE OF SCOTLAND

- 1398 - The Duke of Rothesay

- 1643 - The Duke of Hamilton

- 1663 - The Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry (1684)

- 1581 - The Duke of Lennox

- 1701 - The Duke of Argyll

- 1703 - The Duke of Atholl

- 1707 - The Duke of Montrose

- 1707 - The Duke of Roxburghe

- 1476 - The Marquess of Ormonde (Royal House of Stuart since 1600)

- 1599 - The Marquess of Huntly

- 1682 - The Marquess of Queensberry

- 1694 - The Marquess of Tweeddale

- 1701 - The Marquess of Lothian

- 1398 - The Earl of Crawford and Balcarres (1651)

- 1445 - The Earl of Ormonde

- 1452 - The Earl of Erroll

- 1404 - The Countess of Mar

- 1430 - The Countess of Sutherland

- 1457 - The Earl of Rothes

- 1458 - The Earl of Morton

- 1469 - The Earl of Buchan

- 1507 - The Earl of Eglinton

- 1509 - The Earl of Cassilis

- 1555 - The Earl of Caithness

- 1565 - The Earl of Mar and Kellie (1619)

- 1562 - The Earl of Moray

- 1605 - The Earl of Home

- 1605 - The Earl of Perth

- 1606 - The Earl of Abercorn

- 1606 - The Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne (1606)

- 1619 - The Earl of Haddington

- 1623 - The Earl of Galloway

- 1624 - The Earl of Lauderdale

- 1633 - The Earl of Lindsay

- 1633 - The Earl of Loudoun

- 1633 - The Earl of Kinnoull

- 1633 - The Earl of Dumfries and Bute (1703)

- 1633 - The Earl of Elgin and Kincardine (1647)

- 1633 - The Earl of Southesk

- 1633 - The Earl of Wemyss and March (1697)

- 1633 - The Earl of Dalhousie

- 1639 - The Earl of Airlie

- 1641 - The Earl of Leven and Melville (1690)

- 1643 - The Countess of Dysart

- 1646 - The Earl of Selkirk

- 1647 - The Earl of Northesk

- 1660 - The Earl of Dundee

- 1660 - The Earl of Newburgh

- 1661 - The Earl of Forfar

- 1662 - The Earl of Annandale and Hartfell

- 1669 - The Earl of Dundonald

- 1677 - The Earl of Kintore

- 1682 - The Earl of Aberdeen

- 1686 - The Earl of Dunmore

- 1696 - The Earl of Orkney

- 1701 - The Earl of Seafield

- 1703 - The Earl of Stair

- 1703 - The Earl of Rosebery

- 1703 - The Earl of Glasgow

- 1703 - The Earl of Hopetoun

- 1620 - The Viscount (of) Falkland

- 1621 - The Viscount (of) Stormont

- 1641 - The Viscount of Arbuthnott

- 1651 - The Viscount of Oxfuird

- 1442 - The Lord Forbes

- 1445 - The Lord Gray

- 1445 - The Lady Saltoun

- 1449 - The Lord Sinclair

- 1452 - The Lord Borthwick

- 1452 - The Lord Cathcart

- 1464 - The Lord Lovat

- 1488 - The Lord Sempill

- 1490 - The Lady Herries

- 1510 - The Lord Elphinstone

- 1564 - The Lord Torphichen

- 1602 - The Lady Kinloss

- 1604 - The Lord Colville of Culross

- 1607 - The Lord Balfour of Burleigh

- 1609 - The Lord Dingwall

- 1627 - The Lord Napier of Merchistoun

- 1627 - The Lord Fairfax of Cameron

- 1628 - The Lord Reay

- 1633 - The Lord Forrester

- 1643 - The Lord Elibank

- 1647 - The Lord Belhaven and Stenton

- 1651 - The Lord Rollo

- 1651 - The Lord Ruthven of Freeland

- 1681 - The Lord Nairne

- 1690 - The Lord Polwarth

The Jacobite Presence in Toulouse during the Eighteenth Century, by Edward Corp

During much of the eighteenth century there was a significant Jacobite community in Toulouse. This article will discuss its origins, and show how it became more important after 1741.

The diaspora of the Jacobites had started in 1689 when a few hundred English had followed James II and Mary of Modena into exile in France. An English court had then been established in the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, vacant since Louis XIV had transferred the French court to Versailles in 1682. (1) In the years which followed many more English, and a few Scots, had joined the exiled court so that when James II died in 1701 there was a large Jacobite community in and around Saint-Germain. It employed several French servants, including a clerk named Etienne du Mirail de Monnot. (2) And it commissioned an important series of portraits from François de Troy, the painter from Toulouse who ha recently settled in Paris and was beginning to make a successful career at the French court. (3)

Of greater numerical importance was the exile and diaspora of Jacobites from Ireland. After the defeat of the Franco-Jacobite army there in 1690-91, and the consequent Treaty of Limerick in 1691, a very large number of Irish had come to France. There were probably about 40,000 by the end of the 1690s, and more continued to arrive each year during the decades which followed. Many found employment at Saint-Germain, such that the court became Irish as well as English, but the great majority joined the new Irish regiments in the French army. After the treaty of Ryswick, and more particularly after the Treaties of Utrecht and Rastadt in 1713-14, these Irish regiments were reformed. As a result many of the officers and soldiers became unemployed, and took service instead with the Spanish army. The Jacobite diaspora therefore spread from France to Spain, and thence to Sicily and the Italian peninsula. (4)

This diaspora was not only political and military; it was also religious. Ever since the Protestant reformation in England and Scotland in the sixteenth century there have been a large number of English and Scottish schools, colleges, seminaries and convents in Catholic Europe, notably in the Netherlands, France, Spain, Portugal and the Papal States. The gradual English conquest of Ireland, particularly during the seventeenth century, had also produced a similar number of religious foundations for Irish Catholics, particularly in France and Spain. After the revolution of 1688-89, when the Catholic James II was forced into exile by William of Orange, these English, Scottish and Irish Catholic institutions had all retained their loyalty to the exiled Stuart dynasty, and thus had become important Jacobite centres, where the new political and military exiles were welcomed and supported.

The presence in France, Spain and Portugal of a very large number of Catholic exiles also had important commercial implications. English, Irish and Scottish merchants already had trading links with France, Spain and Portugal, but these were greatly facilitated and enhanced when exiled Jacobites became involved in shipping and in overseas trade. It was easier for the merchants in the British Isles to deal with those in foreign countries who spoke the same language and with whom they already had connections.

A King in Exile: James III

For the first twenty-five years after the revolution of 1688-89 the Jacobite diaspora probably had little impact on the city of Toulouse. There had been a small Irish college attached to the university since 1660, and it immediately became a centre of Jacobitism. But that is probably all. This changed, however, at the beginning of 1717 when a large number of Scots arrived in Toulouse. To understand this new development we need to return to the Stuart court in exile at Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

When James II died in 1701 he was succeeded as the de jure King of England, Scotland and Ireland by his thirteen year old son, James III. At the beginning of the following year William III died at Hampton Court and was succeeded as de facto Queen by Anne, a daughter of James II by his first wife and thus the elder half-sister of James III. Although James was recognised as King by Louis XIV, Philip V of Spain, Pope Clement XII and various other princes, it was generally agreed among Jacobite circles that a restoration would have to be deferred until the death of Queen Anne. The years from 1701 to 1714 were therefore a period of waiting. Meanwhile a new generation of Jacobites was born and brought up at Saint-Germain. It included several people who would later come to Toulouse and play a significant role in the development of the town.

There is no need to repeat here in any detail the story of how Louis XIV tried to restore James III to his thrones during the War of the Spanish Succession. (5) But we might usefully recall the main events. In 1708 there was a Franco-Jacobite attempt to invade Scotland, where pro-Stuart sentiment was particularly strong, and where there was considerable opposition to the Anglo-Scottish Treaty of Union of the previous year. It failed, because the French fleet was unable to make a landing on the east coast of Scotland. In 1711-12 the pro-Jacobite members of a Tory government in London intimated to Louis XIV that a restoration would be facilitated if James were to leave France and move to Lorraine. It was therefore agreed in the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 that France and Spain would no longer support James himself, though most of the Jacobite courtiers and their families would be allowed to remain at Saint-Germain with Queen Mary of Modena.

Having moved part of his court to Bar-le-Duc, and thereby distanced himself from France, James then entered into negotiations with the Tory ministers to bring about a peaceful restoration whenever Anne should die. These negotiations failed because they soon reached an impasse. The Tories had passed an Act specifying that all future monarchs had to be or become members of the Anglican Church. James was a Catholic, believed strongly in religious toleration, and refused to convert; and neither side was willing to give way. This meant that when Queen Anne died suddenly in the summer of 1714 she was not succeeded by James but by George, the Elector of Hanover, who had been provisionally offered the throne because he was a Protestant and willing to become an Anglican.

James III was faced with a difficult predicament. A peaceful restoration was no longer possible, yet French help to bring one about was not forthcoming under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht. The only possibility seemed to be to lead a major rising in Scotland, to break the Union, and then invade England from the north. The rising took place in the autumn of 1715, and James III hastily left Lorraine to place himself at its head. Having secretly travelled through France, he landed in Scotland in January 1716, only to discover that the Jacobites had already been defeated. He was obliged to leave after only a few weeks and return to continental Europe, where he was faced with a major problem to find a new place of residence. The Treaty of Utrecht stated that he was not allowed to remain in France. Louis XIV had died in September 1715 and had been succeeded at the head of the French government by the duc d’Orléans, as Regent for Louis XV. Unlike most of the French court, Orléans was pro-Hanoverian and anti-Jacobite. He therefore joined with George I in bringing pressure to bear on the duc de Lorraine to stop James returning to Bar-le-Duc. James had no choice but to go south to Avignon, where Pope Clement XII was willing to give him a refuge. Having sent most of his servants back to join the Queen-Mother at Saint-Germain, he arrived at Avignon with a small court in April 1716.

James III remained at Avignon until February 1717, when he was forced by the duc d’Orléans to cross the Alps and settle in the Papal States. There he would remain for the rest of his life, never to regain his thrones. While he was at Avignon he was joined by about two thousand Scottish Jacobites, many of them Highlanders, newly exiled after the rising of 1715-16. As he could not take all these people to the Papal States, he had to find an alternative place for them to go. And the place chosen was Toulouse.

The Scottish Highlanders

The Highlanders needed to go somewhere well away from Paris, to attract as little attention to themselves as possible, yet a place from which they might be able to return to Scotland when the moment came for the next restoration attempt. On 30 January 1717 the Duke of Mar, then the Jacobite Secretary of State at Avignon, wrote that «the people of quality here with the King and some of his gentlemen are to follow him to Italy, and the rest are to disperse as they find most convenient till he have occasion for their service. Most of the Highlandmen are going towards Toulouse, and, if they be not in numbers in one place, and behave quietly and discreetly, we hope they will not be disturbed.» (6) He informed a correspondent at Saint-Germain that «they are the people of all who have followed the King to France most capable of doing him service at home, when we shall have occasion, and the station they are sent to is the most convenient for transporting them to their own country, when the time comes.» (7)

In February and March 1717, therefore, a large group of Scottish Highlanders arrived in Toulouse to find a temporary home. They traveled from Avignon with as much…

(1) Edward Corp, A Court in Exile: The Stuarts in France, 1689-1718 (Cambridge University Press, 2004)

(2) There are several references to him in Corp, A Court in Exile. When his daughter was baptized at Saint-Germain in November 1704, her godfather was a certain Pierre du Mirail, and her godmother was Anne du Mirail, «veuve du sieur Benoist, commissaire des guides» (C. E. Lart, The Parochial Registers of Saint Germain-en-Laye: Jacobite Extracts, 2 Vols., London, 1910, 1912, vol. 2, p. 64) She later married a Monsieur de Brillac (Royal Archives at Windsor Castle, Stuart Papers – hereafter cited as SP – 239/44, Flyn to Edgar, 6 January 1743).

(3) Edward Corp, The King over the Water: Portraits of the Stuarts in Exile after 1689 (National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2001), p. 37, 40-47; and A Court in Exile, p. 180, 184-93. See also Dominique Brȇme, François de Troy (Paris and Toulouse, 1997).

(4) Thomas O’Connor, ed. The Irish in Europe, 1580-1815 (Dublin, 2001), including an essay by the present author entitled «The Irish at the Jacobite Court of Saint-Germain-en-Laye», at p. 143-156. See also Guy Rowlands, «An Army in Exile: Louis XIV and the Irish Forces of James II in France, 1691-1698», Royal Stuart Papers LX (London, 2001).

(5) A summary is in Daniel Szechi, The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788 (Manchester University Press, 1994). For more detailed coverage, see Corp, A Court in Exile, chapters 1 and 6.

(6) Historical Manuscripts Commission, Calendar of the Stuart Papers preserved at Windsor Castle, 7 volumes (London, 1902-23) – hereafter cited as HMC Stuart – III, p. 490, Mar to Seaforth, 30 January 1717.

(7) Ibid., p. 504, Mar to Dicconson, 2 February 1717.

Pages 128-29 not shown

…cannot properly understand the early history of Freemasonry in Toulouse. (21)

The problem is that Barnewall had so many Jacobite connections that any description of them is bound to be extremely complicated, and difficult to follow. Those who are willing to accept that Barnewall was in fact a committed Jacobite, and that Taillefer [¶] and Pistre were completely wrong to doubt it, might wish to skip over some parts of the following paragraphs. But the evidence needs to be placed on record. And some of it will be referred to again in the later sections of this article.

There were two main branches of the Barnewall family, both of which are relevant because Richard Barnewall was a member of the senior branch, while his mother and wife were both members of the junior branch. The head of the senior branch was Baron Trimleston, a title which had been in the family since 1461. The head of the junior branch was Viscount Kingsland, a title granted by Charles I in 1645 (22) Richard’s father was the 11th Baron Trimleston; his mother was a niece of the 1st Viscount Kingsland, and first cousin of the 2nd Viscount; his wife, who was his second cousin once removed, was the daughter of the 3rd Viscount.

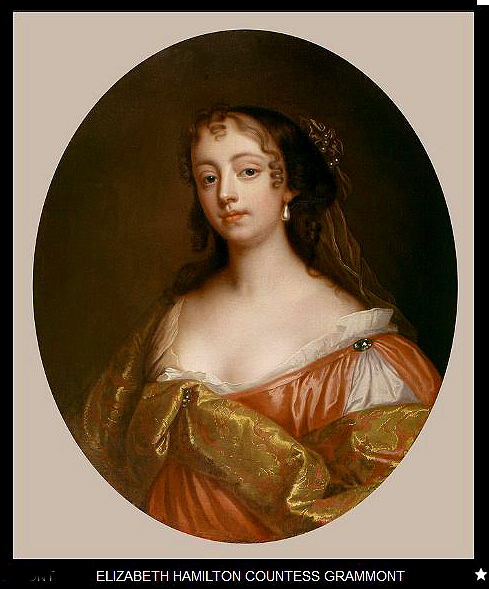

Both branches of the family actively supported James II in the war in Ireland against William of Orange. Richard’s uncle was the 10th Baron, who followed James II into exile and died in Flanders in 1692 while serving in the French army. As the 10th Baron had no children, Richard’s father inherited the family title, as 11th Baron. He had been attained for supporting James II, and it was with difficulty that the attainder was reversed under the pardon granted in the Treaty of Limerick. Richard’s aunt Bridget (sister of the 10th and 11th Barons) was married to Colonel Christopher Nugent. In 1691 she and her husband went to live in France. She became a permanent member of the Jacobite court, and served for many years as a Bedchamber Woman to James III’s sister, Princess Louis Marie. (23) Christopher Nugent was the proprietary colonel of Nugent’s Regiment, and one of the most distinguished of all the Jacobite officers in the French army. He was later promoted to be a Lieutenant-General. (24) The Nugents had six children (Richard Barnewall’s first cousins) who were all brought up in the Château de Saint-Germain during the 1690s (28), and were closely connected with some of the most important members of the Jacobite court. The extent of her connections cannot be fully understood without recourse to a family tree, and must therefore be merely summarized here. The main point to notice is that Mary Hamilton’s own mother (i.e., Frances Barnewall’s grandmother) was married twice, first to George Hamilton (Mary’s father), then to the Duke of Tyrconnell (her step-father).

Her paternal uncles were the Jacobite poet Anthony Hamilton, known in France as comte Antoine Hamilton, and Richard, who was Master of the King’s Robes at Saint-Germain. (29) Her sister, née Francis Hamilton, was married to the 8th Viscount Dillon, elder brother of Arthur, proprietary colonel of Dillon’s Regiment in the French army. (30) Arthur’s wife was the sister of two of the leading English Jacobites at Saint-Germain. (31) They had ten children, one of whom would become Archbishop of Toulouse, all of them brought up at the Château de Saint-Germain.

Lady Kingsland’s step-father, the Duke of Tyrconnell, was James II’s Viceroy in Ireland, and commander-in-chief of the Jacobite forces during the war of 1689-91. The Duchess of Tyrconnell was a Lady of the Bedchamber to the Queen at Saint-Germain, as also was her daughter by her second marriage. This was Lady Kingsland’s half-sister Charlotte, who married the 2nd Earl of Tyrconnell and had a son (Francis Barnewall’s first cousin) who became 3rd Earl of Tyrconnell and French ambassador at Berlin. (32)

We should add that Francis Barnewall’s father, the 3rd Viscount Kingsland, had been brought up under the guardianship of his brother-in-law, Baron Nugent of Riverstown, a first cousin of Richard Barnewall’s uncle Christopher Nugent. Lord Nugent’s three nephews (successively 3rd, 4th, and 5th Earls of Westmeath) were all in France, and the youngest, John, was an equerry to Queen Mary of Modena at Saint-Germain. (33)

Let us conclude, therefore, that when Richard Barnewall, the man who would later introduce Freemasonry to Toulouse, married his cousin Frances Barnewall, it was a particularly important union between two of the best connected young Jacobites in Ireland. They were both Irish and Catholic, as were all their relations mentioned in the detailed paragraphs above, at a time when being an Irish Catholic was virtually synonymous with being a Jacobite. The marriage took place in Ireland in July 1725 when Richard was seventeen.

It is not known when Richard Barnewall was initiated as a Freemason, but it was presumably in Dublin in the late 1720s. The Grand Lodge of Dublin was created in 1725, and the Grand Lodge of Munster was created in 1726. They united in 1731 to form the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Ireland, and during the 1730s Barnewall and his brother-in-law became two of its most important members. The 4th Viscount Kingsland (Henry Benedict Barnewall) was elected Grand Master in 1733. Richard Barnewall served as Deputy Grand Master from 1734 to 1737. (34) These years coincided with the power struggle in Paris between the Jacobite and Hanoverian Freemasons to control the Grande Loge de France.

In 1740 Richard Barnewall’s wife died, leaving him with two sons, Nicholas and John. The boys needed to be educated, so Richard, like so many other Irish Catholics at that time, took them to France to place them in one of the Irish colleges. He left Dublin in April 1740, accompanied by John Barnewall, the only one of his five brothers who had also remained in Ireland until then. (35) The group of two men and two boys travelled to Saint-Germain-en-Laye, where they were met by their relations. In 1740 the latter included Richard’s brother Robert (later 12th Baron Trimleston); his Nugent cousins (children of General Christopher and Bridget Nugent); his wife’s first cousin, the 3rd Earl of Tyrconnell; his wife’s many Dillon cousins (children of General Arthur, Jacobite Earl Dillon); and his wife’s Nugent of Westmeath relations, John Nugent, his Italian wife Margaret (née Molza) and their eight children. Richard Barnewall remained in this circle at Saint-Germain with his two sons and his brother for over a year, until 1741. (36)

The Barnewall’s lived with Mrs. Elizabeth O’Neil, an English Jacobite whose Irish husband had been a Page of the Bedchamber to James III. (37) She had recently been widowed, was short of money, and was therefore able and willing to provide rented accommodations for the group of visiting Irish Jacobites. (38) For some reason Richard Barnewall decided not to have his sons educated at the Irish college in Paris, and chose the Irish college at Toulouse instead. We do not know why, but a possible explanation is that Richard Barnewall was a Jacobite and not a Hanoverian Freemason.

In 1738 the 5th Earl of Derwentwater [†] had been evicted from his position as Grand Master of the Grande Loge de France, and replaced by the duc d’Antin. This was because the Jacobites had lost control of the Grande Loge to the pro-Hanoverian Freemasons. As a result Lord Derwentwater had settled at Saint-Germain and created a new Jacobite Loge of Freemasons, independent of the Grande Loge de France, with exclusive new higher grades, known as the «Rite Ecossais Ancien et Accepté». The most important member of the new lodge, apart from Derwentwater himself was Sir Andrew Ramsay, previously Grand Orateur of the Grande Loge de France and author of the celebrated «Discourse». (39)

While he was at Saint-Germain-en-Laye from 1740 to 1741 Barnewall must have met Derwentwater and Ramsay, though there is no documentary evidence to prove it. But this contact with Derwentwater and Ramsay might help explain why Barnewall decided to go south to Toulouse. (40)

It appears that there was an important pro-Jacobite French Freemason living in Toulouse. This was Antoine-Joseph de Niquet, marquise de Sérane, who was Président à mortier in the Parlement de Toulouse. He had apparently been initiated in Paris by Lord Derwentwater at some time between 1736 and 1738. (41) It is possible, therefore, that Richard Barnewall decided to go to Toulouse in 1741 for two reasons; to educate his sons in the Irish college; and to create a new Jacobite lodge with his brother John Barnewall, under the protection of Niquet. The lodge was created in December 1741, with Richard Barnewall as Master, his brother John as Senior Warden, and a French nobleman (the comte de Valence) as Junior Warden. The lodge was called «Saint-Jean Ancienne», a reference to the Rite Ecossais Ancien et Accepté. (42) The lodge quickly recruited new members and, according to the Archbishop of Toulouse (Charles-Antoine de la Roche-Aymon), writing in March 1742, «leurs assemblées sont fréquentes et nombreuses, et les gens qui les composent sont de tout état, de tout âge, et de toute condition, et le secret en est impénétrable». (43)

We do not know to what extent these original Freemasons in Toulouse included French people as well as Jacobite exiles. Moreover the Archbishop failed to distinguish between Irish and English – a normal mistake in eighteenth century France – so we cannot even be sure of the origins of the Jacobites. He simply wrote that «deux Anglais nommes Barnaval [sic]… ont fait depuis quelque temps dans cette ville un etablissement de ‘franmassons’». (44) A letter sent by another correspondent to Cardinal Fleury in April 1742 provides some extra information: «je suis persuadé comme tout le monde l’est en cette ville que la quantité d’Anglais qui y viennent depuis quelque temps y ont introduit ce nouvel établissement.» (45) Taken at face value, this suggests that the Barnewalls were not the only Irish [?] Jacobites who arrived in Toulouse at this time to create the lodge. But we are told that they also recruited local French people: «il a été fait de la connaissance de tout le monde trios a quatre soupers dans les cabarets de cette ville pour y recevoir des ‘francmaçons’ habitants de cette ville… [le] 11 de ce mois on fit un souper de ‘francmaçons’ que l’on qualifia de tenure de loge de cet ordre dans une sale qui avait été destinée les années precedents à une concert qui était établis et qui ne subsiste plus en cette ville.» (46) If Barnewall was able to fill a small concert room with Freemasons, he must have been very successful in attracting local recruits. As the great supper on 11 March 1742 was three months after the founding of the loge on 2 December 1741, it was no doubt the occasion when the first Brothers to be received were allowed to progress from being «postulants» to become «les novices ou les apprentifs». (47)

The establishment of the Jacobite lodge in Toulouse created a particular problem for the Archbishop. In 1738 James III had asked Pope Clement XII to issue the Bull In Eminenti condemning Freemasonry. The purpose of the Bull had been to condemn Hanoverian Freemasonry as it was practiced in Florence and (after 1737-38) by the Grande Loge de France, and not Jacobite Freemasonry as it was practiced in Rome, Lisbon and Saint-Germain-en-Laye (48) – and now Toulouse. But this had not been publically stated, and the Archbishop was unlikely to have been aware of it. Moreover the situation in France was more complicated, because the Bull In Eminenti had never been registered or officially accepted. The Archbishop therefore asked for specific guidance: «Je ne sais pas si vous croirez devoir fermer les yeux sur ces sortes d’associations, quand même elles seraient innocents. Dans un pays ou les génies sont aussi vifs qu’en celui-ci, cela peut avoir des suites qu’il serait bon de prévenir.» (49)

The result was a repetition in Toulouse of the rivalry between Jacobite and Hanoverian Freemasonry which had already occurred in Paris, and before that in London. In 1743 the

(21) This section is heavily indebted to Taillefer’s book [¶] for the chronological facts concerning the early history of Freemasonry in Toulouse. My interpretation of those facts, however, is very different.

[¶] Nouvelle Histoire de Toulouse - Histoire des villes - Univers de la France (Toulouse, France), par Michel Taillefer, Publie par Privat: Toulouse, 2002

(22) The genealogies of the Barnewall families, and of the other families mentioned in this section, as well as the correct spelling of their names and titles, may easily be checked in any of the British Peerages, two of which are available among the Usuels of the Bibliothèque Municipale de Toulouse.

(23) Corp, A Court in Exile, p. 366.

(24) J. C. O’Callaghan, History of the Irish Brigades in the Service of France (Glasgow, 1870; and facsimile edition, Shannon, 1969), p. 153-55.

(25) The details of the Jacobites married and born at Saint-Germain are given in Lart. op. cit.

(26) André Kervella, La Passion Écossaise (Paris, 2002), p. 506.

(27) One might add that Richard Barnewall’s grandmother was the sister of the 1st Earl of Limerick, who went into exile at Saint-Germain-en-Laye and died there. See Corp, «The Irish at the Jacobite court of Saint-Germain-en-Laye», in O’Connor, op. cit., p. 148-149.

(28) Edward Corp, «Les courtisans francais à la cour d’Angleterre à Saint-Germain-en-Laye», Cahiers Saint-Simon noº 28, Année 2000, p. 63. Her visit to Fontainebleau with James II and Mary of Modena in the autumn of 1695 was recorded by the marquis de Dangeau. See Philippe de Courcillon, marquis de Dangeau, Journal, eds. E. Soulié and L. Dussieux, 19 vols (Paris 1854-60), vol. 5, p. 285, 29 September 1695.

(29) There are many references to both brothers in Corp, A Court in Exile.

(30) O’Callaghan, op. cit., p. 27-28, 46-43.

(31) Lady Dillon was born Catherine Sheldon. Her brother Dominic was Under-Governor of James III when the king was a boy, then Vice-Chamberlain. Her brother Ralph was one of James III’s equerries.

(32) There are many references to both ladies in Corp, A Court in Exile.

(33) There are also many references to John Nugent and his family in Corp, A Court in Exile.

(34) Taillefer, op. cit., p. 21.

(35) Ibid., p. 23.

(36) Richard Barnewall’s relations at Saint-Germain are frequently mentioned in the correspondence between Saint-Germain and the Stuart court in Rome, preserved in the Stuart Papers at Windsor Castle.

(37) Taillefer, op. cit., p. 18; Corp, A Court in Exile, p. 300, 337.

(38) SP 199/61, petition of Mrs Elizabeth O’Neill to James III, 14 July 1737; SP Box 2/425, Mrs Elizabeth O’Neill to James III, undated [1740s].

[†] Lord Charles Radclyffe, 5th Earl of Derwentwater.

(39) Corp, A Court in Exile, p. 341-42. See also my forthcoming article «La Franc-maçonnerie jacobite et la bulle In eminenti d’avril 1738», to be published in La Règle d’Abraham, nº 18, December 2004.

(40) It might also help to explain why the Bibliothèque Municipale de Toulouse owns two contemporary manuscript copies of Sir Andrew Ramsay’s «Discours prononcé à la reception des frée-macons» (MS 932, f.76; and MS 1213, f.1). They are discussed in Georges Lamoine, Discours prononcé à la Réception des francs-maçons par le Chevalier André-Michael de Ramsay (Editions SNES, Toulouse, no date).

(41) Taillefer, op. cit., p. 26. The document recording the fact is dated 1773, and states that Niquet was initiated by Derwentwater in Paris « il y a environ quarante ans». Lord Derwentwater was in Rome until 1736, and he left Paris for Saint-Germain in 1738.

(42) A copy made in December 1774 of the original charter of 2 December 1741 is quoted in full in Taillefer, op. cit., p. 15-16.

(43) Taillefer, op. cit., p. 17. La-Roche-Aymon to Fleury, 21 March 1742.

(44) Ibid.

(45) Ibid., p. 17, Maniban to Fleury, 18 April 1742.

(46) Ibid.

(47) Wellcome Library, London, MS 5744/10, Ramsay to Caumont, 16 April 1737: «Nous avons dans notre société trois sortes de confrères; les novices ou les apprentifs; les compagnons ou les profès; les maitres ou les adeptes… [On est] trois mois postulant, trois mois novice, et trois mois compagnon, avant que d’etre admis aux grands mysteres et par là devenir homme nouveau. »

(48) See above, note 39.

(49) Taillefer, op. cit., p. 198.

Pages 135-42 not shown

1768, was signed by the duc de FitzJames, Archbishop Dillon, Lieutenant-General Sir Peter Nugent (his first cousin once removed), and the latter’s brother-in-law Lieutenant-General John Redmond. (128)

Richard Barnewall had previously lived in the Château de la Mirolle (near Verdun-sur-Garonne), but he now gave that to his son, and bought for himself the larger Terre et Seigneurie of Granel, near Lafrançaise (north-west of Montauban), where he died in 1778. Nicholas Barnewall, like Justin MacCarthy, then remained in Toulouse until the French Revolution, when he emigrated to Ireland. Because he had been naturalized all his possessions were seized and auctioned in 1794. Two years later, however, he succeeded his first cousin as 14th Baron Trimleston. He never returned to Toulouse, and died in Ireland in 1813. (129)

We might also mention another Jacobite who began a successful career at Toulouse. This was a Scottish priest named Seignelay Colbert, whose family name came from Castlehill in Morayshire. The family’s name was really Cuthbert but, because Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the minister of Louis XIV, had claimed to be descended from a Scottish noble family, the Cuthberts had changed their name to Colbert! The minister’s eldest son had been marquis de Seignelay – hence the rather strange name, Seignelay Colbert. (130) This Colbert became a friend of Nicholas Barnewall, and helped him to deal with his father Robert’s estate when he died in 1778. (131) He also became a close friend of Archbishop Dillon, and was appointed Bishop of Rodez in 1781. When Dillon emigrated to England in 1792, Seignelay Colbert went with him, and was at his bedside when he died in London in 1806. (132) Archbishop Dillon’s funeral service at St. Pancras church London marked the end of the Jacobite presence in Toulouse, and the final return of the exiles to their homeland. It was conducted by Bishop Colbert and attended by various members of the Dillon family, and by Nicholas Barnewall, now Lord Trimleston. (133)

It is not surprising the Jacobite presence in Toulouse came to an end with the French Revolution. The English, Irish and Scots who followed James II and his son James III into exile were both royalists and legitimists, completely out of place in the France of 1792 to 1814, and after 1830. Some of them achieved positions of importance under Louis XVIII and Charles X, but otherwise their loyalties were to the exiled Stuarts. Nevertheless, the legacy of the Jacobite presence in Toulouse can still be found.

There are, of course, the Cours Dillon and the Hôtel MacCarty, already mentioned. There is also a reminder of the Jacobites to be seen in the Musée des Augustins. This is the large painting by Francesco Curadi [Curradi], Le Triomphe de Judith, which was placed in the Chapelle Royale of the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye during the reign of Louis XIV. It was situated beneath the royal tribune, opposite the high altar, so that it was impossible to leave the chapel without seeing it. (134) Archbishop Dillon, grand vicaire Booth and the duc de FitzJames would have seen it virtually every day throughout their childhood and youth. So too would Richard Barnewall and the abbé MacCarthy when they were at Saint-Germain. It was not removed from the chapel until 1794, and has been in the Musée des Augustins since 1805. (135) But that is not the only legacy of the Jacobites in Toulouse today – there is also the collection of books in the Bibliothèque Municipale which was originally owned by the Earl of Middleton and the Duke of Perth, and purchased by the Freemason from Montauban, Jean-Jaques LeFranc de Pompignan. (136)

The Jacobite presence in Toulouse lasted for about a hundred years, from 1689 until the 1790s when the remaining exiles and ex-patriots were obliged to leave the town and return to their home countries. By then the Jacobite cause was a thing of the past, of no relevance to a new generation which was more concerned with Jacobines. Prince Charles, whom the Pope had refused to recognize as King Charles III, died in 1788. His younger brother Prince Henry, Cardinal York, who might have been King Henry IX, died in 1807. The Irish College was closed with the rest of the university, and when the next British people arrived in Toulouse, with the army of the Marquess (later Duke) of Wellington, they were employed by the Hanoverian King George III. There had been British people in Toulouse before 1689, and others would arrive after April 1814, but the presence of a community of Jacobites, consciously desiring the restoration of the Stuart dynasty, was confined to the period from 1689 to 1792.

While it lasted Toulouse was one of the many Jacobite centres spread across continental Europe from Lisbon to St Petersburg. The most important were at Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Paris, at Rome, and at Madrid. Toulouse might perhaps best be regarded as a satellite or outpost of the Jacobite community in the Château de Saint-Germain. One historian of the town has written that «since the 1680s, Toulouse had hosted a substantial community of Jacobites… Two scions of local Jacobite families, Henri de Nesmond and Arthur Dillon, rose to become archbishops of Toulouse, while the latter also left his mark on the city by sponsoring the construction of the promenades by the Garonne that bear his name. Another, the comte de MacCarthy [sic], gained a reputation throughout Europe for his extensive collection of fine books.» (137) This, however, is misleading. Henri de Nesmond was French, and had no family links with the Jacobites. Arthur Dillon was the first member of his family to have any connection with Toulouse. Justin MacCarthy was born in Ireland and was brought to Toulouse on the recommendation of abbé MacCarthy. They were not members of local Jacobite families.

What Dillon and MacCarthy had in common were their close and direct links with the much larger Jacobite community at Saint-Germain. The same could be said of Richard Barnewall and virtually every Jacobite mentioned by name in this article. Even

Pages 145-48 not shown

Frances Barnewall, daughter of Nicholas Barnewall, 3rd Viscount Barnewall of Kingsland and Mary Hamilton, Viscountess Barnewall of Kingsland, the daughter of Sir George Hamilton, Comte Hamilton and Frances Jenyns, Duchess of Tyrconnell.

"The Jacobite Presence in Toulouse during the Eighteenth Century,” by Edward Corp, in: Diasporas Histoire et Sociétés, No. 5 - Généalogies Rȇvées, Collectif, Presses Universitaires de Toulouse-Le Mirail: Toulouse, 2007 (pgs. 124 et seq)

During much of the eighteenth century there was a significant Jacobite community in Toulouse. This article will discuss its origins, and show how it became more important after 1741.

The diaspora of the Jacobites had started in 1689 when a few hundred English had followed James II and Mary of Modena into exile in France. An English court had then been established in the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, vacant since Louis XIV had transferred the French court to Versailles in 1682. (1) In the years which followed many more English, and a few Scots, had joined the exiled court so that when James II died in 1701 there was a large Jacobite community in and around Saint-Germain. It employed several French servants, including a clerk named Etienne du Mirail de Monnot. (2) And it commissioned an important series of portraits from François de Troy, the painter from Toulouse who ha recently settled in Paris and was beginning to make a successful career at the French court. (3)

Of greater numerical importance was the exile and diaspora of Jacobites from Ireland. After the defeat of the Franco-Jacobite army there in 1690-91, and the consequent Treaty of Limerick in 1691, a very large number of Irish had come to France. There were probably about 40,000 by the end of the 1690s, and more continued to arrive each year during the decades which followed. Many found employment at Saint-Germain, such that the court became Irish as well as English, but the great majority joined the new Irish regiments in the French army. After the treaty of Ryswick, and more particularly after the Treaties of Utrecht and Rastadt in 1713-14, these Irish regiments were reformed. As a result many of the officers and soldiers became unemployed, and took service instead with the Spanish army. The Jacobite diaspora therefore spread from France to Spain, and thence to Sicily and the Italian peninsula. (4)

This diaspora was not only political and military; it was also religious. Ever since the Protestant reformation in England and Scotland in the sixteenth century there have been a large number of English and Scottish schools, colleges, seminaries and convents in Catholic Europe, notably in the Netherlands, France, Spain, Portugal and the Papal States. The gradual English conquest of Ireland, particularly during the seventeenth century, had also produced a similar number of religious foundations for Irish Catholics, particularly in France and Spain. After the revolution of 1688-89, when the Catholic James II was forced into exile by William of Orange, these English, Scottish and Irish Catholic institutions had all retained their loyalty to the exiled Stuart dynasty, and thus had become important Jacobite centres, where the new political and military exiles were welcomed and supported.

The presence in France, Spain and Portugal of a very large number of Catholic exiles also had important commercial implications. English, Irish and Scottish merchants already had trading links with France, Spain and Portugal, but these were greatly facilitated and enhanced when exiled Jacobites became involved in shipping and in overseas trade. It was easier for the merchants in the British Isles to deal with those in foreign countries who spoke the same language and with whom they already had connections.

A King in Exile: James III

For the first twenty-five years after the revolution of 1688-89 the Jacobite diaspora probably had little impact on the city of Toulouse. There had been a small Irish college attached to the university since 1660, and it immediately became a centre of Jacobitism. But that is probably all. This changed, however, at the beginning of 1717 when a large number of Scots arrived in Toulouse. To understand this new development we need to return to the Stuart court in exile at Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

When James II died in 1701 he was succeeded as the de jure King of England, Scotland and Ireland by his thirteen year old son, James III. At the beginning of the following year William III died at Hampton Court and was succeeded as de facto Queen by Anne, a daughter of James II by his first wife and thus the elder half-sister of James III. Although James was recognised as King by Louis XIV, Philip V of Spain, Pope Clement XII and various other princes, it was generally agreed among Jacobite circles that a restoration would have to be deferred until the death of Queen Anne. The years from 1701 to 1714 were therefore a period of waiting. Meanwhile a new generation of Jacobites was born and brought up at Saint-Germain. It included several people who would later come to Toulouse and play a significant role in the development of the town.

There is no need to repeat here in any detail the story of how Louis XIV tried to restore James III to his thrones during the War of the Spanish Succession. (5) But we might usefully recall the main events. In 1708 there was a Franco-Jacobite attempt to invade Scotland, where pro-Stuart sentiment was particularly strong, and where there was considerable opposition to the Anglo-Scottish Treaty of Union of the previous year. It failed, because the French fleet was unable to make a landing on the east coast of Scotland. In 1711-12 the pro-Jacobite members of a Tory government in London intimated to Louis XIV that a restoration would be facilitated if James were to leave France and move to Lorraine. It was therefore agreed in the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 that France and Spain would no longer support James himself, though most of the Jacobite courtiers and their families would be allowed to remain at Saint-Germain with Queen Mary of Modena.

Having moved part of his court to Bar-le-Duc, and thereby distanced himself from France, James then entered into negotiations with the Tory ministers to bring about a peaceful restoration whenever Anne should die. These negotiations failed because they soon reached an impasse. The Tories had passed an Act specifying that all future monarchs had to be or become members of the Anglican Church. James was a Catholic, believed strongly in religious toleration, and refused to convert; and neither side was willing to give way. This meant that when Queen Anne died suddenly in the summer of 1714 she was not succeeded by James but by George, the Elector of Hanover, who had been provisionally offered the throne because he was a Protestant and willing to become an Anglican.

James III was faced with a difficult predicament. A peaceful restoration was no longer possible, yet French help to bring one about was not forthcoming under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht. The only possibility seemed to be to lead a major rising in Scotland, to break the Union, and then invade England from the north. The rising took place in the autumn of 1715, and James III hastily left Lorraine to place himself at its head. Having secretly travelled through France, he landed in Scotland in January 1716, only to discover that the Jacobites had already been defeated. He was obliged to leave after only a few weeks and return to continental Europe, where he was faced with a major problem to find a new place of residence. The Treaty of Utrecht stated that he was not allowed to remain in France. Louis XIV had died in September 1715 and had been succeeded at the head of the French government by the duc d’Orléans, as Regent for Louis XV. Unlike most of the French court, Orléans was pro-Hanoverian and anti-Jacobite. He therefore joined with George I in bringing pressure to bear on the duc de Lorraine to stop James returning to Bar-le-Duc. James had no choice but to go south to Avignon, where Pope Clement XII was willing to give him a refuge. Having sent most of his servants back to join the Queen-Mother at Saint-Germain, he arrived at Avignon with a small court in April 1716.

James III remained at Avignon until February 1717, when he was forced by the duc d’Orléans to cross the Alps and settle in the Papal States. There he would remain for the rest of his life, never to regain his thrones. While he was at Avignon he was joined by about two thousand Scottish Jacobites, many of them Highlanders, newly exiled after the rising of 1715-16. As he could not take all these people to the Papal States, he had to find an alternative place for them to go. And the place chosen was Toulouse.

The Scottish Highlanders

The Highlanders needed to go somewhere well away from Paris, to attract as little attention to themselves as possible, yet a place from which they might be able to return to Scotland when the moment came for the next restoration attempt. On 30 January 1717 the Duke of Mar, then the Jacobite Secretary of State at Avignon, wrote that «the people of quality here with the King and some of his gentlemen are to follow him to Italy, and the rest are to disperse as they find most convenient till he have occasion for their service. Most of the Highlandmen are going towards Toulouse, and, if they be not in numbers in one place, and behave quietly and discreetly, we hope they will not be disturbed.» (6) He informed a correspondent at Saint-Germain that «they are the people of all who have followed the King to France most capable of doing him service at home, when we shall have occasion, and the station they are sent to is the most convenient for transporting them to their own country, when the time comes.» (7)

In February and March 1717, therefore, a large group of Scottish Highlanders arrived in Toulouse to find a temporary home. They traveled from Avignon with as much…

(1) Edward Corp, A Court in Exile: The Stuarts in France, 1689-1718 (Cambridge University Press, 2004)

(2) There are several references to him in Corp, A Court in Exile. When his daughter was baptized at Saint-Germain in November 1704, her godfather was a certain Pierre du Mirail, and her godmother was Anne du Mirail, «veuve du sieur Benoist, commissaire des guides» (C. E. Lart, The Parochial Registers of Saint Germain-en-Laye: Jacobite Extracts, 2 Vols., London, 1910, 1912, vol. 2, p. 64) She later married a Monsieur de Brillac (Royal Archives at Windsor Castle, Stuart Papers – hereafter cited as SP – 239/44, Flyn to Edgar, 6 January 1743).

(3) Edward Corp, The King over the Water: Portraits of the Stuarts in Exile after 1689 (National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2001), p. 37, 40-47; and A Court in Exile, p. 180, 184-93. See also Dominique Brȇme, François de Troy (Paris and Toulouse, 1997).

(4) Thomas O’Connor, ed. The Irish in Europe, 1580-1815 (Dublin, 2001), including an essay by the present author entitled «The Irish at the Jacobite Court of Saint-Germain-en-Laye», at p. 143-156. See also Guy Rowlands, «An Army in Exile: Louis XIV and the Irish Forces of James II in France, 1691-1698», Royal Stuart Papers LX (London, 2001).

(5) A summary is in Daniel Szechi, The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688-1788 (Manchester University Press, 1994). For more detailed coverage, see Corp, A Court in Exile, chapters 1 and 6.

(6) Historical Manuscripts Commission, Calendar of the Stuart Papers preserved at Windsor Castle, 7 volumes (London, 1902-23) – hereafter cited as HMC Stuart – III, p. 490, Mar to Seaforth, 30 January 1717.

(7) Ibid., p. 504, Mar to Dicconson, 2 February 1717.

Pages 128-29 not shown

…cannot properly understand the early history of Freemasonry in Toulouse. (21)

The problem is that Barnewall had so many Jacobite connections that any description of them is bound to be extremely complicated, and difficult to follow. Those who are willing to accept that Barnewall was in fact a committed Jacobite, and that Taillefer [¶] and Pistre were completely wrong to doubt it, might wish to skip over some parts of the following paragraphs. But the evidence needs to be placed on record. And some of it will be referred to again in the later sections of this article.

There were two main branches of the Barnewall family, both of which are relevant because Richard Barnewall was a member of the senior branch, while his mother and wife were both members of the junior branch. The head of the senior branch was Baron Trimleston, a title which had been in the family since 1461. The head of the junior branch was Viscount Kingsland, a title granted by Charles I in 1645 (22) Richard’s father was the 11th Baron Trimleston; his mother was a niece of the 1st Viscount Kingsland, and first cousin of the 2nd Viscount; his wife, who was his second cousin once removed, was the daughter of the 3rd Viscount.

Both branches of the family actively supported James II in the war in Ireland against William of Orange. Richard’s uncle was the 10th Baron, who followed James II into exile and died in Flanders in 1692 while serving in the French army. As the 10th Baron had no children, Richard’s father inherited the family title, as 11th Baron. He had been attained for supporting James II, and it was with difficulty that the attainder was reversed under the pardon granted in the Treaty of Limerick. Richard’s aunt Bridget (sister of the 10th and 11th Barons) was married to Colonel Christopher Nugent. In 1691 she and her husband went to live in France. She became a permanent member of the Jacobite court, and served for many years as a Bedchamber Woman to James III’s sister, Princess Louis Marie. (23) Christopher Nugent was the proprietary colonel of Nugent’s Regiment, and one of the most distinguished of all the Jacobite officers in the French army. He was later promoted to be a Lieutenant-General. (24) The Nugents had six children (Richard Barnewall’s first cousins) who were all brought up in the Château de Saint-Germain during the 1690s (28), and were closely connected with some of the most important members of the Jacobite court. The extent of her connections cannot be fully understood without recourse to a family tree, and must therefore be merely summarized here. The main point to notice is that Mary Hamilton’s own mother (i.e., Frances Barnewall’s grandmother) was married twice, first to George Hamilton (Mary’s father), then to the Duke of Tyrconnell (her step-father).

Her paternal uncles were the Jacobite poet Anthony Hamilton, known in France as comte Antoine Hamilton, and Richard, who was Master of the King’s Robes at Saint-Germain. (29) Her sister, née Francis Hamilton, was married to the 8th Viscount Dillon, elder brother of Arthur, proprietary colonel of Dillon’s Regiment in the French army. (30) Arthur’s wife was the sister of two of the leading English Jacobites at Saint-Germain. (31) They had ten children, one of whom would become Archbishop of Toulouse, all of them brought up at the Château de Saint-Germain.

Lady Kingsland’s step-father, the Duke of Tyrconnell, was James II’s Viceroy in Ireland, and commander-in-chief of the Jacobite forces during the war of 1689-91. The Duchess of Tyrconnell was a Lady of the Bedchamber to the Queen at Saint-Germain, as also was her daughter by her second marriage. This was Lady Kingsland’s half-sister Charlotte, who married the 2nd Earl of Tyrconnell and had a son (Francis Barnewall’s first cousin) who became 3rd Earl of Tyrconnell and French ambassador at Berlin. (32)

We should add that Francis Barnewall’s father, the 3rd Viscount Kingsland, had been brought up under the guardianship of his brother-in-law, Baron Nugent of Riverstown, a first cousin of Richard Barnewall’s uncle Christopher Nugent. Lord Nugent’s three nephews (successively 3rd, 4th, and 5th Earls of Westmeath) were all in France, and the youngest, John, was an equerry to Queen Mary of Modena at Saint-Germain. (33)

Let us conclude, therefore, that when Richard Barnewall, the man who would later introduce Freemasonry to Toulouse, married his cousin Frances Barnewall, it was a particularly important union between two of the best connected young Jacobites in Ireland. They were both Irish and Catholic, as were all their relations mentioned in the detailed paragraphs above, at a time when being an Irish Catholic was virtually synonymous with being a Jacobite. The marriage took place in Ireland in July 1725 when Richard was seventeen.

It is not known when Richard Barnewall was initiated as a Freemason, but it was presumably in Dublin in the late 1720s. The Grand Lodge of Dublin was created in 1725, and the Grand Lodge of Munster was created in 1726. They united in 1731 to form the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Ireland, and during the 1730s Barnewall and his brother-in-law became two of its most important members. The 4th Viscount Kingsland (Henry Benedict Barnewall) was elected Grand Master in 1733. Richard Barnewall served as Deputy Grand Master from 1734 to 1737. (34) These years coincided with the power struggle in Paris between the Jacobite and Hanoverian Freemasons to control the Grande Loge de France.

In 1740 Richard Barnewall’s wife died, leaving him with two sons, Nicholas and John. The boys needed to be educated, so Richard, like so many other Irish Catholics at that time, took them to France to place them in one of the Irish colleges. He left Dublin in April 1740, accompanied by John Barnewall, the only one of his five brothers who had also remained in Ireland until then. (35) The group of two men and two boys travelled to Saint-Germain-en-Laye, where they were met by their relations. In 1740 the latter included Richard’s brother Robert (later 12th Baron Trimleston); his Nugent cousins (children of General Christopher and Bridget Nugent); his wife’s first cousin, the 3rd Earl of Tyrconnell; his wife’s many Dillon cousins (children of General Arthur, Jacobite Earl Dillon); and his wife’s Nugent of Westmeath relations, John Nugent, his Italian wife Margaret (née Molza) and their eight children. Richard Barnewall remained in this circle at Saint-Germain with his two sons and his brother for over a year, until 1741. (36)

The Barnewall’s lived with Mrs. Elizabeth O’Neil, an English Jacobite whose Irish husband had been a Page of the Bedchamber to James III. (37) She had recently been widowed, was short of money, and was therefore able and willing to provide rented accommodations for the group of visiting Irish Jacobites. (38) For some reason Richard Barnewall decided not to have his sons educated at the Irish college in Paris, and chose the Irish college at Toulouse instead. We do not know why, but a possible explanation is that Richard Barnewall was a Jacobite and not a Hanoverian Freemason.

In 1738 the 5th Earl of Derwentwater [†] had been evicted from his position as Grand Master of the Grande Loge de France, and replaced by the duc d’Antin. This was because the Jacobites had lost control of the Grande Loge to the pro-Hanoverian Freemasons. As a result Lord Derwentwater had settled at Saint-Germain and created a new Jacobite Loge of Freemasons, independent of the Grande Loge de France, with exclusive new higher grades, known as the «Rite Ecossais Ancien et Accepté». The most important member of the new lodge, apart from Derwentwater himself was Sir Andrew Ramsay, previously Grand Orateur of the Grande Loge de France and author of the celebrated «Discourse». (39)

While he was at Saint-Germain-en-Laye from 1740 to 1741 Barnewall must have met Derwentwater and Ramsay, though there is no documentary evidence to prove it. But this contact with Derwentwater and Ramsay might help explain why Barnewall decided to go south to Toulouse. (40)