Seven Sermons to the Dead

http://www.american-buddha.com/lit.sevensermonsjung.htm

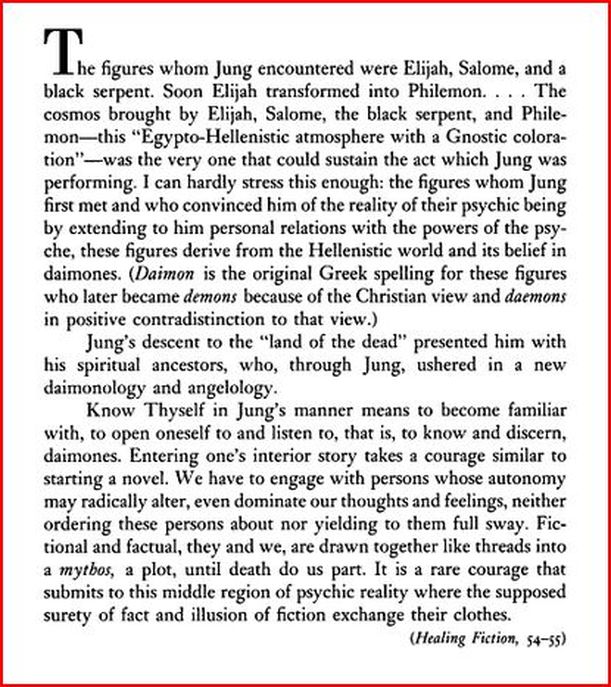

Jung's painting titled, "Septem Sermones ad Mortuous" - completed around 1918 while working on Liber Novus, and subsequently give as a gift to H.G. Baynes

Near the end of his life, Jung spoke to Aniela Jaffe about the Septem Sermones

and explained "that the discussions with the dead [in the Seven

Sermons] formed the prelude to what he would subsequently communicate

to the world, and that their content anticipated his later

books. 'From that time on, the dead have become ever more distinct for

me as the voices of the unanswered. unresolved and unredeemed.' " [The Red Book, p346 n78]

Being a part, man cannot grasp the whole. He is at its mercy. He may assent to it, or rebel against it; but he is always caught up by it and enclosed within it. He is dependent upon it and is sustained by it. Love is his light and his darkness, whose end he cannot see. ~Carl Jung; Memories Dreams and Reflections; Page 354

In Memories, Jung recounted what followed:

Around five o'clock in the afternoon on Sunday the front doorbell began ringing frantically ... Everyone immediately looked to see who was there, but there was no one in sight. I was sitting near the doorbell, and not heard it but saw it moving. We all simply stared at one another. The atmosphere was thick, believe me! Then I knew something had to happen. The whole house was as if there was a crowd present, crammed full of spirits. They were packed deep right up to the door and the air was so thick it was scarcely possible to breathe. As for myself, I was all aquiver with the question: "For God's sake, what in the world is this?" Then they cried out in chorus, "We have come back from Jerusalem where we found not what we sought." That is the beginning of the Septem Sermones.

Then it began to flow out of me, and in the course of three evenings the thing was written. As soon as I took up the pen, the whole ghastly assemblage evaporated. The room quieted and the atmosphere cleared. The haunting was over. [126]

The dead had appeared in a fantasy on January 17, 1914, and had said that they were about to go to Jerusalem to pray at the holiest graves. [127] Their trip had evidently not been successful. The Septem Sermones ad Mortuos is a culmination of the fantasies of this period. It is a psychological cosmology cast in the form of a gnostic creation myth.

http://www.american-buddha.com/redbookjung.tran.htm

Not one tittle of Christian law is abrogated, but instead we are adding a new one: accepting the lament of the dead. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 298, Footnote 187.

Buber has been led astray by a poem in Gnostic style I made 44 years ago for a friend's birthday celebration (a private print!), a poetic paraphrase of the psychology of the unconscious. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 571.

Being a part, man cannot grasp the whole. He is at its mercy. He may assent to it, or rebel against it; but he is always caught up by it and enclosed within it. He is dependent upon it and is sustained by it. Love is his light and his darkness, whose end he cannot see. ~Carl Jung; Memories Dreams and Reflections; Page 354

In Memories, Jung recounted what followed:

Around five o'clock in the afternoon on Sunday the front doorbell began ringing frantically ... Everyone immediately looked to see who was there, but there was no one in sight. I was sitting near the doorbell, and not heard it but saw it moving. We all simply stared at one another. The atmosphere was thick, believe me! Then I knew something had to happen. The whole house was as if there was a crowd present, crammed full of spirits. They were packed deep right up to the door and the air was so thick it was scarcely possible to breathe. As for myself, I was all aquiver with the question: "For God's sake, what in the world is this?" Then they cried out in chorus, "We have come back from Jerusalem where we found not what we sought." That is the beginning of the Septem Sermones.

Then it began to flow out of me, and in the course of three evenings the thing was written. As soon as I took up the pen, the whole ghastly assemblage evaporated. The room quieted and the atmosphere cleared. The haunting was over. [126]

The dead had appeared in a fantasy on January 17, 1914, and had said that they were about to go to Jerusalem to pray at the holiest graves. [127] Their trip had evidently not been successful. The Septem Sermones ad Mortuos is a culmination of the fantasies of this period. It is a psychological cosmology cast in the form of a gnostic creation myth.

http://www.american-buddha.com/redbookjung.tran.htm

Not one tittle of Christian law is abrogated, but instead we are adding a new one: accepting the lament of the dead. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 298, Footnote 187.

Buber has been led astray by a poem in Gnostic style I made 44 years ago for a friend's birthday celebration (a private print!), a poetic paraphrase of the psychology of the unconscious. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 571.

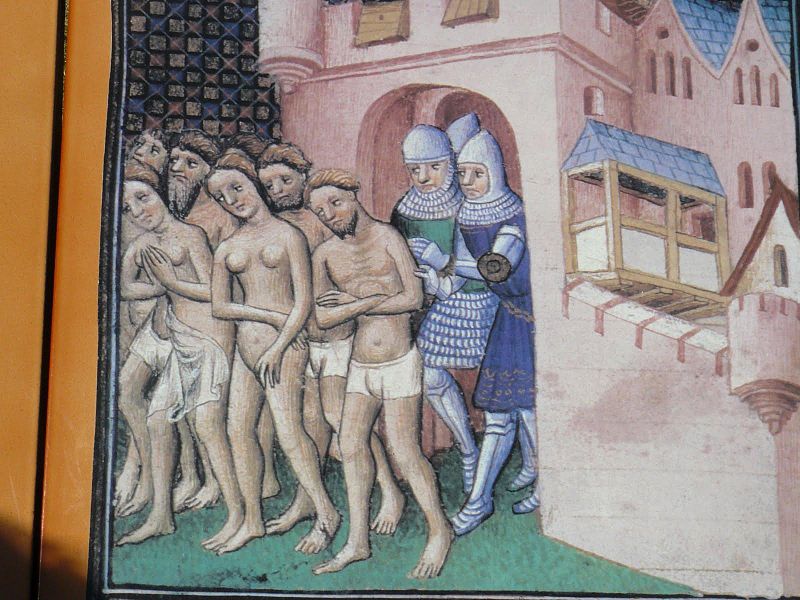

St Michael subduing Satan and weighing the Souls of...

Lelio Orsi, attributed to (1508/11 - 1587)

The lamentations of the dead filled the air at the time, and their misery became so loud that even the living were saddened, and became tired and sick of life and yearned to die to this world already in their living bodies.

And thus you too lead the dead to their completion with your work of salvation.

~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 278, Footnote 188.

The souls of the dead "know" only what they knew at the moment of death, and nothing beyond that…

Later, when I wrote the Septem Sermones ad Mortuos, once again it was the dead who addressed crucial questions to me.

They came so they said "back from Jerusalem, where they found not what they sought."

This had surprised me greatly at the time, for according to the traditional views the dead are the possessors of great knowledge.

People have the idea that the dead know far more than we, for Christian doctrine teaches that in the hereafter we shall "see face to face."

Apparently, however, the souls of the dead "know" only what they knew at the moment of death, and nothing beyond that. Hence their endeavor to penetrate into life in order to share in the knowledge of men.

I frequently have a feeling that they are standing directly behind us, waiting to hear what answer we will give to them, and what answer to destiny.

It seems to me as if they were dependent on the living for receiving answers to their questions, that is, on those who have survived them and exist in a world of change: as if omniscience or, as I might put it, omniconsciousness, were not at their disposal, but could flow only into the psyche of the living, into a soul bound to a body.

The mind of the living appears, therefore, to hold an advantage over that of the dead in at least one point: in the capacity for attaining clear and decisive cognitions.

As I see it, the three-dimensional world in time and space is like a system of co-ordinates; what is here separated into ordinates and abscissae may appear ''there," in space-timelessness, as a primordial image with many aspects, perhaps as a diffuse cloud of cognition surrounding an archetype.

Yet a system of co-ordinates is necessary if any distinction of discrete contents is to be possible.

Any such operation seems to us unthinkable in a state of diffuse omniscience, or, as the case may be, of subjectless consciousness, with no spatiotemporal demarcations.

Cognition, like generation, presupposes an opposition, a here and there, an above and below, a before and after. ~Carl Jung; Memories Dreams and Reflections; Page 308

The lamentations of the dead filled the air at the time, and their misery became so loud that even the living were saddened, and became tired and sick of life and yearned to die to this world already in their living bodies.

And thus you too lead the dead to their completion with your work of salvation.

~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 278, Footnote 188.

The souls of the dead "know" only what they knew at the moment of death, and nothing beyond that…

Later, when I wrote the Septem Sermones ad Mortuos, once again it was the dead who addressed crucial questions to me.

They came so they said "back from Jerusalem, where they found not what they sought."

This had surprised me greatly at the time, for according to the traditional views the dead are the possessors of great knowledge.

People have the idea that the dead know far more than we, for Christian doctrine teaches that in the hereafter we shall "see face to face."

Apparently, however, the souls of the dead "know" only what they knew at the moment of death, and nothing beyond that. Hence their endeavor to penetrate into life in order to share in the knowledge of men.

I frequently have a feeling that they are standing directly behind us, waiting to hear what answer we will give to them, and what answer to destiny.

It seems to me as if they were dependent on the living for receiving answers to their questions, that is, on those who have survived them and exist in a world of change: as if omniscience or, as I might put it, omniconsciousness, were not at their disposal, but could flow only into the psyche of the living, into a soul bound to a body.

The mind of the living appears, therefore, to hold an advantage over that of the dead in at least one point: in the capacity for attaining clear and decisive cognitions.

As I see it, the three-dimensional world in time and space is like a system of co-ordinates; what is here separated into ordinates and abscissae may appear ''there," in space-timelessness, as a primordial image with many aspects, perhaps as a diffuse cloud of cognition surrounding an archetype.

Yet a system of co-ordinates is necessary if any distinction of discrete contents is to be possible.

Any such operation seems to us unthinkable in a state of diffuse omniscience, or, as the case may be, of subjectless consciousness, with no spatiotemporal demarcations.

Cognition, like generation, presupposes an opposition, a here and there, an above and below, a before and after. ~Carl Jung; Memories Dreams and Reflections; Page 308

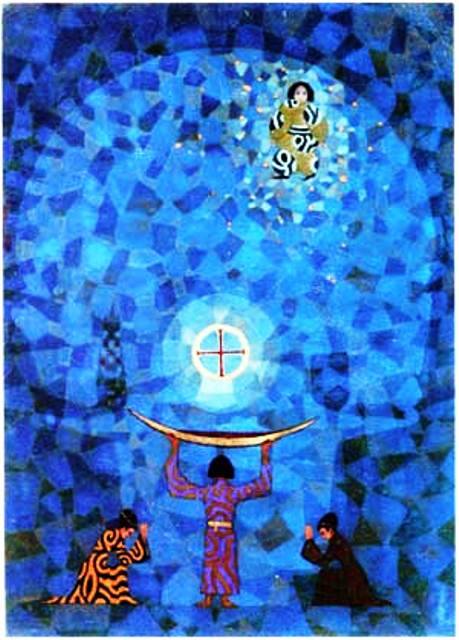

Jacob Böhme, Theosophia Revelata, THREEFOLD LIFE OF MAN, Dreifaches Leben

The unconscious is not just evil by nature, it is also the source of the highest good: not only dark but also light, not only bestial, semi-human, and demonic but superhuman, spiritual, and, in the classical sense of the word, "divine." ~Carl Jung

The knowledge of death came to me that night, from the dying that engulfs the world. I saw how we live toward death, how the swaying golden wheat sinks together under the scythe of the reaper, / like a smooth wave on the sea-beach. He who abides in

common life becomes aware of death with fear. Thus the fear of death drives him toward singleness. He does not live there, but he becomes aware of life and is happy; since in singleness he is one who becomes, and has overcome death. He overcomes death through overcoming common life. He does not live his individual being, since he is not what he is, but what he becomes.

One who becomes grows aware of life, whereas one who simply exists never will, since he is in the midst of life. He needs the heights and singleness to become aware of life. But in life he becomes aware of death. And it is good that you become aware

of collective death, since then you know why your singleness and your heights are good. Your heights are like the moon that luminously wanders alone and through the night looks eternally clear. Sometimes it covers itself and then you are totally in the

darkness of the earth, but time and again it fills itself out with light. The death of the earth is foreign to it. Motionless and clear, it sees the life of the earth from afar, without enveloping haze and streaming oceans. Its unchanging form has been solid from eternity. It is the solitary clear light of the night, the individual being, and the near fragment of eternity.

From there you look out, cold, motionless, and radiating. With otherworldly silvery light and green twilights, you pour out into the distant horror. You see it but your gaze is clear and cold. Your hands are red from living blood, but the moonlight of your gaze is motionless. It is the life blood of your brother, yes, it is your own blood, but your gaze remains luminous and embraces the entire horror and the earth's round. Your gaze rests on silvery seas, on snowy peaks, on blue valleys, and you do not hear the groaning and howling of the human animal.

The moon is dead. Your soul went to the moon, to the preserver of souls. Thus the soul moved toward death. I went into the inner death and saw that outer dying is better than inner death. And I decided to die outside and to live within. For that reason I turned away and sought the place of the inner life. ~Carl Jung; Red Book.

The knowledge of death came to me that night, from the dying that engulfs the world. I saw how we live toward death, how the swaying golden wheat sinks together under the scythe of the reaper, / like a smooth wave on the sea-beach. He who abides in

common life becomes aware of death with fear. Thus the fear of death drives him toward singleness. He does not live there, but he becomes aware of life and is happy; since in singleness he is one who becomes, and has overcome death. He overcomes death through overcoming common life. He does not live his individual being, since he is not what he is, but what he becomes.

One who becomes grows aware of life, whereas one who simply exists never will, since he is in the midst of life. He needs the heights and singleness to become aware of life. But in life he becomes aware of death. And it is good that you become aware

of collective death, since then you know why your singleness and your heights are good. Your heights are like the moon that luminously wanders alone and through the night looks eternally clear. Sometimes it covers itself and then you are totally in the

darkness of the earth, but time and again it fills itself out with light. The death of the earth is foreign to it. Motionless and clear, it sees the life of the earth from afar, without enveloping haze and streaming oceans. Its unchanging form has been solid from eternity. It is the solitary clear light of the night, the individual being, and the near fragment of eternity.

From there you look out, cold, motionless, and radiating. With otherworldly silvery light and green twilights, you pour out into the distant horror. You see it but your gaze is clear and cold. Your hands are red from living blood, but the moonlight of your gaze is motionless. It is the life blood of your brother, yes, it is your own blood, but your gaze remains luminous and embraces the entire horror and the earth's round. Your gaze rests on silvery seas, on snowy peaks, on blue valleys, and you do not hear the groaning and howling of the human animal.

The moon is dead. Your soul went to the moon, to the preserver of souls. Thus the soul moved toward death. I went into the inner death and saw that outer dying is better than inner death. And I decided to die outside and to live within. For that reason I turned away and sought the place of the inner life. ~Carl Jung; Red Book.

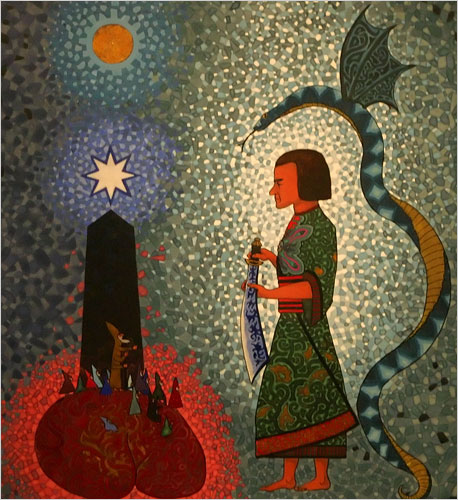

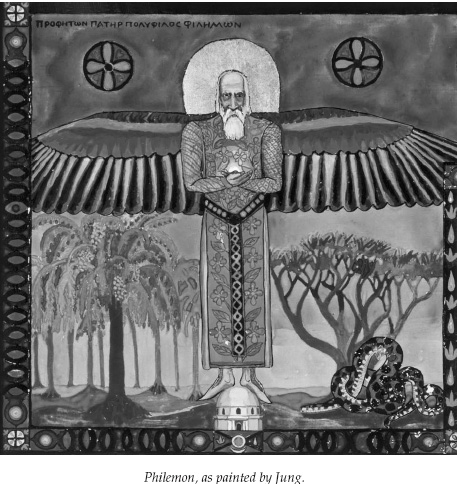

Who is Jung’s Philemon?

http://stottilien.com/2011/02/14/the-red-book-english/

Dr. Jung replied, “Only myself.” ~Carl Jung to Alice Raphael in 1935

My Philemon and Baucis… have nothing to do with that renowned ancient couple or the tradition connected with them. I gave this couple the names merely to elevate the characters. The persons and relations are similar, and hence the use of the names has a good effect. ~[ 6 June 1831, cited in Goethe, Faust, tr. W. Arndt, Norton Critical Edition, (New York, 1976, p. 428.)]

Collective & Personal Psyche

We shall probably get nearest to the truth if we think of the conscious and personal psyche as resting upon the broad basis of an inherited and universal psychic disposition

which is as such unconscious, and that our personal psyche bears the same relation to the collective psyche as the individual to society.

But equally, just as the individual is not merely a unique and separate being, but is also a social being, so the human psyche is not a self-contained and wholly individual

phenomenon, but also a collective one.

And just as certain social functions or instincts are opposed to the interests of single individuals, so the human psyche exhibits certain functions or tendencies which, on account of their collective nature, are opposed to individual needs.

The reason for this is that every man is born with a highly differentiated brain and is thus assured of a wide range of mental functioning which is neither developed ontogenetically nor acquired.

But, to the degree that human brains are uniformly differentiated, the mental functioning thereby made possible is also collective and universal.

This explains, for example, the interesting fact that the unconscious processes of the most widely separated peoples and races show a quite remarkable correspondence, which displays itself, among other things, in the extraordinary but well-authenticated analogies between the forms and motifs of autochthonous myths.

The universal similarity of human brains leads to the universal possibility of a uniform mental functioning.

This functioning is the collective psyche.

Inasmuch as there are differentiations corresponding to race, tribe, and even family, there is also a collective psyche limited to race, tribe, and family over and above the "universal" collective psyche.

To borrow an expression from Pierre Janet, the collective psyche comprises the parties infirieures of the psychic functions, that is to say those deep-rooted, well-nigh automatic portions of the individual psyche which are inherited and are to be found everywhere, and are thus impersonal or supra-personal.

Consciousness plus the personal unconscious constitutes the parties superieures of the psychic functions, those portions, therefore, that are developed ontogenetically and

acquired.

Consequently, the individual who annexes the unconscious heritage of the collective psyche to what has accrued to him in the course of his ontogenetic development, as though it were part of the latter, enlarges the scope of his personality in an illegitimate way and suffers the consequences.

In so far as the collective psyche comprises the parties inferieures of the psychic functions and thus forms the basis of every personality, it has the effect rushing and devaluing the personality.

This shows itself either in the aforementioned stifling of self-confidence or else in an unconscious heightening of the ego's importance to the point of a pathological will to power. ~Carl Jung; The Portable Jung; Pages 93-94.

http://stottilien.com/2011/02/14/the-red-book-english/

Dr. Jung replied, “Only myself.” ~Carl Jung to Alice Raphael in 1935

My Philemon and Baucis… have nothing to do with that renowned ancient couple or the tradition connected with them. I gave this couple the names merely to elevate the characters. The persons and relations are similar, and hence the use of the names has a good effect. ~[ 6 June 1831, cited in Goethe, Faust, tr. W. Arndt, Norton Critical Edition, (New York, 1976, p. 428.)]

Collective & Personal Psyche

We shall probably get nearest to the truth if we think of the conscious and personal psyche as resting upon the broad basis of an inherited and universal psychic disposition

which is as such unconscious, and that our personal psyche bears the same relation to the collective psyche as the individual to society.

But equally, just as the individual is not merely a unique and separate being, but is also a social being, so the human psyche is not a self-contained and wholly individual

phenomenon, but also a collective one.

And just as certain social functions or instincts are opposed to the interests of single individuals, so the human psyche exhibits certain functions or tendencies which, on account of their collective nature, are opposed to individual needs.

The reason for this is that every man is born with a highly differentiated brain and is thus assured of a wide range of mental functioning which is neither developed ontogenetically nor acquired.

But, to the degree that human brains are uniformly differentiated, the mental functioning thereby made possible is also collective and universal.

This explains, for example, the interesting fact that the unconscious processes of the most widely separated peoples and races show a quite remarkable correspondence, which displays itself, among other things, in the extraordinary but well-authenticated analogies between the forms and motifs of autochthonous myths.

The universal similarity of human brains leads to the universal possibility of a uniform mental functioning.

This functioning is the collective psyche.

Inasmuch as there are differentiations corresponding to race, tribe, and even family, there is also a collective psyche limited to race, tribe, and family over and above the "universal" collective psyche.

To borrow an expression from Pierre Janet, the collective psyche comprises the parties infirieures of the psychic functions, that is to say those deep-rooted, well-nigh automatic portions of the individual psyche which are inherited and are to be found everywhere, and are thus impersonal or supra-personal.

Consciousness plus the personal unconscious constitutes the parties superieures of the psychic functions, those portions, therefore, that are developed ontogenetically and

acquired.

Consequently, the individual who annexes the unconscious heritage of the collective psyche to what has accrued to him in the course of his ontogenetic development, as though it were part of the latter, enlarges the scope of his personality in an illegitimate way and suffers the consequences.

In so far as the collective psyche comprises the parties inferieures of the psychic functions and thus forms the basis of every personality, it has the effect rushing and devaluing the personality.

This shows itself either in the aforementioned stifling of self-confidence or else in an unconscious heightening of the ego's importance to the point of a pathological will to power. ~Carl Jung; The Portable Jung; Pages 93-94.

7th June 1955

Dear Mrs. Raphael!

Thank you for your interesting letter, which I will try to answer.

Ad Philemon and Baucis: a typical Goethean answer to Eckermann! trying to conceal his vestiges.

Philemon (= kiss), the loving one, the simple old loving couple, close to the earth and aware of the Gods, the complete opposite to the Superman Faust, the product of the devil.

Incidentally: in my tower at Bollingen is a hidden inscription: Philemon sacrum Fausti poenitentia.

When I first encountered the archetype of the old wise man, he called himself Philemon.

In Alchemy Philemon and Baucis represented the artifex or vir sapiens and the soror mystica (Zosimos-Theosebeia, Nicolas Flamel-Péronelle, Mr. South and his daughter in the XIXth Cent.) and the pair in the mutus liber (about 1677).

The opus Alchemical tries to produce the Philosopher’s stone sny. with the “homo altus” the Hermes or Christ.

The risk is, that the artifex becomes identical with the goal of his opus.

He becomes inflated and crazy: “multi perierunt in opere nostro!”

There is a “demon” in the prima materia, that drives people crazy.

That’s what happened to Faust and incidentally to the German nation.

The end was the great conflagration of German cities, where all the simple people burned to death.

It will be the death of nations if the H-bombs shall explode.

The fire allusions in Faust II are quite sinister: they point to a great conflagration, that leads up to the end of Faust himself.

In the thereafter he has to begin life again as a puer and has to learn the true values of love and wisdom, neglected in his earthly existence, whereas the true artifex learns them through and in his opus, avoiding the danger of inflation.

The wanderer in Alchemy refers to the peregrinatio of the artifex (Mich. Majer Symb. Aureae Mensae) through the four quarters of the world (individuation).

Faust II is a great prophecy of the future anticipated in alchemical symbolism.

The archetype is always past, present and future.

The puer Knabe Lenker, Homunculus, Euphorion, all three disappear in the fire, i.e., Faust’s own future will be destroyed through the fire of concupiscentia and its madness.

My best wishes,

yours sincerely,

C. G. Jung.

In later years, Jung explicitly linked his Philemon with the figure in the second part of Goethe’s Faust.1 On 5 January 1942, he wrote to Paul Schmitt:

You have hit the mark absolutely: all off a sudden with terror it became clear to me that I have taken over Faust as my heritage, and moreover as the advocate and avenger of Philemon and Baucis, who, unlike Faust the superman, are host of the gods in a ruthless and godforsaken age…

I would give the earth to know whether Goethe himself knew why he called the two old people “Philemon” and “Baucis.” Faust sinned against these first parents.

One must have one foot in the grave, though, before one understands this secret properly.

Here, the Faustian inheritance is redeemed through a movement back to the classical figures of Philemon and Baucis, through Goethe’s invocation of them; a movement from Goethe to Ovid.

In Memories, Jung recounted: when Faust, in his hubris and self-inflation, caused the murder of Philemon and Baucis, I felt guilty, quite as if I myself in the past had helped commit the murder of these the two old people.

This strange idea alarmed me, and I regarded it as my responsibility to atone for this crime, or to prevent its repetition. ~ C. G. Jung Letters, volume 1: 1906–1950, Ed. Gerhard Adler in with Aniela Jaffé, tr. R. F. C. Hull, (Bollingen Series, Princeton, Princeton University Press, pp. 309–10). See also Jung to Hermann Keyserling, 2 January 1928, ibid., p. 49.

My Philemon and Baucis… have nothing to do with that renowned ancient couple or the tradition connected with them. I gave this couple the names merely to elevate the characters. The persons and relations are similar, and hence the use of the names has a good effect. ~[ 6 June 1831, cited in Goethe, Faust, tr. W. Arndt, Norton Critical Edition, (New York, 1976, p. 428.)]

http://www.philemonfoundation.org/resources/jung_history/volume_2_issue_2/who_is_jungs_philemon_a_unpublished_letter

http://www.amazon.com/Goethe-Philosophers-Stone-Symbolical-Patterns/dp/B0007DKE4C/ref=sr_1_fkmr0_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1396706762&sr=8-1-fkmr0&keywords=Goethe+and+the+Philosophers’+Stone%3A+Symbolical+Patterns+in+‘The+Parable’+and+the+Second+Part+of+‘Faust’

And so it is death is indeed a fearful piece of brutality; there is no sense pretending otherwise.

It is brutal not only as a physical event, but far more so psychically: a human being is torn away from us, and what remains is the icy stillness of death.

There no longer exists any hope of a relationship, for all the bridges have been smashed at one blow. Those who deserve a long life are cut off in the prime of their years, and good-for-nothings live to a ripe old age. This is a cruel reality which we have no right to sidestep.

The actual experience of the cruelty and wantonness of death can so embitter us that we conclude there is no merciful God, no justice, and no kindness. From another point of view, however, death appears as a joyful event. In the light of eternity, it is a wedding, a Mysterium Coniunctionis.

The soul attains, as it were, its missing half, it achieves wholeness. On Greek sarcophagi the joyous element was represented by dancing girls, on Etruscan tombs by banquets.When the pious Cabbalist Rabbi Simon ben Jochai came to die, his friends said that he was celebrating his wedding. To this day it is the custom in many regions to hold a picnic on the graves on All Souls' Day. Such customs express the feeling that death is really a festive occasion. ~Carl Jung, Memories Dreams and Reflections

It is brutal not only as a physical event, but far more so psychically: a human being is torn away from us, and what remains is the icy stillness of death.

There no longer exists any hope of a relationship, for all the bridges have been smashed at one blow. Those who deserve a long life are cut off in the prime of their years, and good-for-nothings live to a ripe old age. This is a cruel reality which we have no right to sidestep.

The actual experience of the cruelty and wantonness of death can so embitter us that we conclude there is no merciful God, no justice, and no kindness. From another point of view, however, death appears as a joyful event. In the light of eternity, it is a wedding, a Mysterium Coniunctionis.

The soul attains, as it were, its missing half, it achieves wholeness. On Greek sarcophagi the joyous element was represented by dancing girls, on Etruscan tombs by banquets.When the pious Cabbalist Rabbi Simon ben Jochai came to die, his friends said that he was celebrating his wedding. To this day it is the custom in many regions to hold a picnic on the graves on All Souls' Day. Such customs express the feeling that death is really a festive occasion. ~Carl Jung, Memories Dreams and Reflections

THE RETURN OF THE DEAD

http://carljungdepthpsychology.blogspot.com/2013/02/the-return-of-dead.html

In Memories, Jung recounted what followed:

Around five o'clock in the afternoon on Sunday the front doorbell began ringing frantically ... Everyone immediately looked to see who was there, but there was no one in sight. I was sitting near the doorbell, and not heard it but saw it moving. We all simply stared at one another. The atmosphere was thick, believe me! Then I knew something had to happen. The whole house was as if there was a crowd present, crammed full of spirits. They were packed deep right up to the door and the air was so thick it was scarcely possible to breathe. As for myself, I was all aquiver with the question:

"For God's sake, what in the world is this?" Then they cried out in chorus, "We have come back from Jerusalem where we found not what we sought."

That is the beginning of the Septem Sermones. Then it began to flow out of me, and in the course of three evenings the thing was written. As soon as I took up the pen, the whole ghastly assemblage evaporated. The room quieted and the atmosphere cleared. The haunting was over.

http://carljungdepthpsychology.blogspot.com/2013/02/the-return-of-dead.html

In Memories, Jung recounted what followed:

Around five o'clock in the afternoon on Sunday the front doorbell began ringing frantically ... Everyone immediately looked to see who was there, but there was no one in sight. I was sitting near the doorbell, and not heard it but saw it moving. We all simply stared at one another. The atmosphere was thick, believe me! Then I knew something had to happen. The whole house was as if there was a crowd present, crammed full of spirits. They were packed deep right up to the door and the air was so thick it was scarcely possible to breathe. As for myself, I was all aquiver with the question:

"For God's sake, what in the world is this?" Then they cried out in chorus, "We have come back from Jerusalem where we found not what we sought."

That is the beginning of the Septem Sermones. Then it began to flow out of me, and in the course of three evenings the thing was written. As soon as I took up the pen, the whole ghastly assemblage evaporated. The room quieted and the atmosphere cleared. The haunting was over.

The confidence people have in their beliefs is not a measure of the quality of evidence but of the coherence of the story that the mind has managed to construct.

This is a mechanism that takes whatever information is available and makes the best possible story out of the information currently available, and tells you very little about information it doesn’t have. So what you get are people jumping to conclusions. I call this a “machine for jumping to conclusions.”

That will very often create a flaw. It will create overconfidence. The confidence people have in their beliefs is not a measure of the quality of evidence [but] of the coherence of the story that the mind has managed to construct. Quite often you can construct very good stories out of very little evidence. . . . People tend to have great belief, great faith in the stories that are based on very little evidence.

What’s interesting is that many a time people have intuitions that they’re equally confident about except they’re wrong. That happens through the mechanism I call “the mechanism of substitution.” You have been asked a question, and instead you answer another question, but that answer comes by itself with complete confidence, and you’re not aware that you’re doing something that you’re not an expert on because you have one answer. Subjectively, whether it’s right or wrong, it feels exactly the same. Whether it’s based on a lot of information, or a little information, this is something that you may step back and have a look at. But the subjective sense of confidence can be the same for intuition that arrives from expertise, and for intuitions that arise from heuristics. . . .

http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2013/10/30/daniel-kahneman-intuition/

This is a mechanism that takes whatever information is available and makes the best possible story out of the information currently available, and tells you very little about information it doesn’t have. So what you get are people jumping to conclusions. I call this a “machine for jumping to conclusions.”

That will very often create a flaw. It will create overconfidence. The confidence people have in their beliefs is not a measure of the quality of evidence [but] of the coherence of the story that the mind has managed to construct. Quite often you can construct very good stories out of very little evidence. . . . People tend to have great belief, great faith in the stories that are based on very little evidence.

What’s interesting is that many a time people have intuitions that they’re equally confident about except they’re wrong. That happens through the mechanism I call “the mechanism of substitution.” You have been asked a question, and instead you answer another question, but that answer comes by itself with complete confidence, and you’re not aware that you’re doing something that you’re not an expert on because you have one answer. Subjectively, whether it’s right or wrong, it feels exactly the same. Whether it’s based on a lot of information, or a little information, this is something that you may step back and have a look at. But the subjective sense of confidence can be the same for intuition that arrives from expertise, and for intuitions that arise from heuristics. . . .

http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2013/10/30/daniel-kahneman-intuition/

Now for the Gnostics and this is their real secret the psyche existed as a source of knowledge just as much as it did for the alchemists. Aside from the psychology of the unconscious, contemporary science and philosophy know only of what is outside, while faith knows only of the inside, and then only in the Christian form imparted to it by the passage of the centuries, beginning with St. Paul and the gospel of St. John.

.

Faith, quite as much as science with its traditional objectivity, is absolute, which is why faith and knowledge can no more agree than Christians can with one another. ~ Carl Jung, Aion, Psychology of Christian Alchemical Symbolism, Paragraph 269.

.

Faith, quite as much as science with its traditional objectivity, is absolute, which is why faith and knowledge can no more agree than Christians can with one another. ~ Carl Jung, Aion, Psychology of Christian Alchemical Symbolism, Paragraph 269.

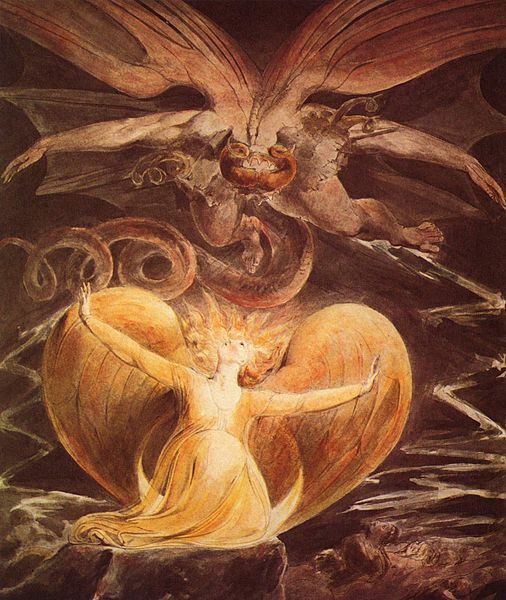

Blake, Great Red Dragon & Woman Clothed with the Sun

"Thus your soul is your own self in the spiritual world. As the abode of the spirits, however, the spiritual world is also an outer world. Just as you are also not alone in the visible world, but are surrounded by objects that belong to you and obey only you, you also have thoughts that belong to you and obey only you. But just as you are surrounded in the visible world by things and beings that neither belong to you nor obey you, you are also surrounded in the spiritual world by thoughts and beings of thought that neither obey you nor belong to you. Just as you engender or bear your physical children, and just as they grow up and separate themselves from you to live their own fate, you also produce or give birth to beings of thought which separate themselves from you and live their own lives. Just as we leave our children when we grow old and give our body back to the earth, I separate myself from my God, the sun, and sink into the emptiness of matter and obliterate the image of my child in me. This happens in that I accept the nature of matter and allow the force of my form to flow into emptiness. Just as I gave birth anew to the sick God through my engendering force, I henceforth animate the emptiness of matter from which the formation of evil grows."

~Carl Jung, Red Book, Page 288

~Carl Jung, Red Book, Page 288

An Excerpt from ”The Boundless Expanse: Jung’s Reflections on Death and Life”

by Sonu Shamdasani

Jung's lectures before the Zofingia society also provide indication of his first formulations of the concept of life and his clear commitment to vitalism.

It was clear to him at this time that a positive definition of an irreducible life force was essential for postmortem existence in any form to be conceivable.

As I've traced in detail elsewhere, throughout his career, Jung remained committed to a position that could broadly be described as neo-vitalist.

Thus works such as Jung's 1928 paper on the "energetics of the soul," which at first glance appear to be far removed from such questions have a critical bearing on them, in laying the basis for an ontology in which survival is at least theoretically conceivable.

For example in 1930, he wrote to Alice Raphael:

... Bergson is quite right when he thinks of the possibility of relatively loose connection between the brain and consciousness, because despite of our ordinary experience the connection might be less tight than we suppose. There is no reason why one shouldn't suppose that consciousness could exist detached from a brain . . . the real difficulty

begins ... when you should prove that there is consciousness without a brain. It would amount to the hitherto unproven fact of an evidence that there are ghosts. I think that this is the most difficult thing in the world to create an evidence in that respect entirely satisfactory from a scientific point of view . How can one establish an indisputable evidence of a consciousness without a brain? I might be satisfied if such a consciousness would be able to write an intelligent book, invent new apparatuses, provide us with new information that couldn't possibly be found in human brains, and if it were evident that there would be no high power medium among the spectators. But such a thing is quite unthinkable ... Trance conditions are certainly very interesting and I know a good deal about them—though never enough. But they wouldn't yield any strict evidence, because they are conditions of a living brain.

Consciousness detached from the brain? Nothing could be further from the current fad for neuro-scientific reductionism.

In retrospect Jung recalled that a pivotal experience in his understanding of the relations between the living and the dead was a dream that occurred whilst he was at work on his book, Transformations and Symbols of the Libido. In the autumn of 1910, he undertook a bicycle tour in Northern Italy and was staying in Arona:

In the dream I was in an assemblage of distinguished spirits of earlier centuries;' the feeling was similar to the one I had later towards the 'illustrious ancestors' in the black rock temple of my 1944 vision.

The conversation was conducted in Latin. A gentleman with a long, curly wig addressed me and asked a difficult question, the gist of which I could no longer recall after I woke up. I understood him, but did not have a sufficient command of the language to answer him in Latin.

I felt so profoundly humiliated by this that the emotion awakened me. At the very moment of awakening I thought of the book I was then working on, Transformations and Symbols of the Libido, and had such inferiority feelings about the unanswered question that I immediately took the train home in order to get back to work ... I had to work, to find the question.

Not until years later did I understand the dream and my reaction. The bewigged gentleman was a kind of ancestral spirit or spirit of the dead, who had addressed questions to me—in vain! It was still too soon, I had not yet come so far, but I had an obscure feeling that by working on my book I would be answering the question that had been asked. It had been asked by, as it were, my spiritual forefathers, in the hope and expectation that they would learn what they had not been able to find out during their time on earth, since the answer had first to be created in the centuries that followed.

Here, Jung indicates that his first task was to attempt to reconstruct the question that had been posed to him, and that the manner in which he did this was to continue working on his book. In this connection it seems important that one central problematic in this work was actually the question of inheritance: our relation to the past and its continued relevance in the present.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, a number of figures became interested in organic or ancestral memory, a notion buttressed by Lamarckian views on inheritance and Ernst Haeckel's biogenic law, the contention that the individual developed recapitulated the development of the species. Figures such as Thomas Laycock, Théodule Ribot, and Stanley Hall contended that many of our actions and reactions should be viewed as ancestral reversions, and denoted the activation of mnemonic residues laid down in the course of human evolution, and that such residues resided in a phylogenetic layer of the unconscious.

As Gustave Le Bon noted in 1894, "Infinitely more numerous than the living, the dead are also infinitely more powerful than them. They govern the immense domain of the unconscious, this invisible domain which contains under its empire all the manifestations of intelligence and character."

As I've reconstructed elsewhere, the views of the organic memory theories became a constitutive element of Jung's theory formation in Transformations and Symbols of the Libido. As Jung put it, "The soul possesses in some degree a historical stratification, whereby the oldest stratum of which would correspond to the unconscious"

It is not clear whether the bewigged gentleman would have been satisfied with a lecture on phylogenetic psychology, or that he would have followed all the twists and turns of Jung's argument in this work, tracing the myriad transformations of the chameleon-like ever-present libido, which not a few of the living have had a hard time with. However, it is clear that Jung himself was not satisfied with the answers he had given in this work. As he recounted, soon after the completion of the work, a more serious question arose, to which he could not give an answer at that time, namely, what was his myth.

This question lay at the heart of Jung's confrontation with the unconscious. Perhaps it would not be going too far to say that this question may have lain closer to the one which may have been posed by the bewigged gentleman, Viewed from this perspective, Jung's self-exploration can be seen as his attempt to articulate an answer.

Further light on these connections may be shed by a consideration of Jung's Septem Sermones ad Mortuos, written in 1916. Until now, the Septem Sermones has remained the one significant chapter of what I term Jung's private cosmology that has been published. With the publication of Jung's Red Book, the study of his private cosmology as well as its interplay with his scholarly writings will finally be able to commence.

Till then, there still remains much to be studied in the Sermones. To begin with, they shed important light on what could be termed Jung's theology of the dead.

First, we should retrace their genesis. At the beginning of 1916, Jung experienced a striking series of parapsychological events in his house. In Memories, Jung recounted what followed:

Around five o'clock in the afternoon on Sunday the front-door bell began ringing frantically. It was a bright summer day; the two maids were in the kitchen, from which the open square outside the front door could be seen. Everyone immediately looked to see who was there, but there was no one in sight. I was sitting near the door bell, and not heard it but saw it moving. We all simply stared at one another. The atmosphere was thick, believe me! Then I knew something had to happen. The whole house was as if there was a crowd present, crammed full of spirits. They were packed deep right up to the door and the air was so thick it was scarcely possible to breathe. As for myself, I was all a-quiver with the question: "For God's sake, what in the world is this?" Then they cried out in chorus, "We have come back from Jerusalem where we found not what we sought." That is the beginning of the Septem Sermones. Then it began to flow out of me, and in the course of three evenings the thing was written. As soon as I took up the pen, the whole ghastly assemblage evaporated. The room quieted and the atmosphere cleared. The haunting was over."

The Sermones commence with the following lines: "The dead came back from Jerusalem, where they did not find what they sought, They requested entrance with me and wanted to learn with me, so I taught them."

In the course of their interchange, the dead posed a number of questions to Jung. "We want to know of God. Where is God? Is God dead?" "Speak to us again about the highest God." "Speak to us of gods and devils, cursed one." "Teach us, fool, of the church and holy communion." "There is still one thing which we forgot to say—teach us about man."

In replying to these questions posed by the dead, Jung articulated a comprehensive psycho-theological cosmology. However, initially at least, the dead were apparently unsatisfied with Jung's teaching:

"The dead disappeared grumbling and moaning and their cries died away in the distance." "The dead now raised a great tumult, for they were Christians." "Now the dead howled and raged, for they were unperfected." What do their questions tell us about them?

These "unperfected" Christian dead apparently did not know whether God was alive or dead, as if the perturbations of the teachings of Nietzsche's Zarathustra had reached the beyond; they appeared to be of a polytheistic disposition and were ignorant of the church and knew not of man.

If, like Socrates, these dead had sought to have their questions answered by those already dead, they appear to have been disappointed, and have had no recourse but to turn to the living.

At first glance, this scene provides a striking reversal of what is usually found in spiritualism and its literature, where the living seek and receive instruction from the dead.

Whilst quite struck by this, Jung did not consider it exceptional.

To Aniela Jaffe, he noted that it astonished him that the dead had posed him questions, as one assumes that the dead had greater knowledge than us. It seemed that the dead only knew what they knew when they died, hence their tendency to intrude into our lives.

In this regard he found the Chinese custom that events should be conveyed to the ancestors to be very significant.

It seemed to him that personal development did not stop at death, but was dependent upon the increase of consciousness among the living. Spiritualistic literature indicated that the dead really sought psychological insight.

Unlike his dream at Arona, Jung here was able to note the questions of dead and to reply with detailed answers.

This passage articulates a critical aspect of Jung's private cosmology:

“What is vital here is not just a conviction of the survival of bodily death, but a view of the significance of human life, conceived as a process of the development of consciousness that does not stop at the grave—moreover, a process in which the further development of the dead is dependent on the increase of consciousness of the living. Within this conception, through our terrestrial development, we are in fact aiding the postmortem development of the dead.

The Septem Sermones do not merely articulate a private cosmology. To Aniela Jaffé, Jung commented that they formed a prelude to what he would later communicate to the world in his books. Hence the task was one of conveying to the living what he had already conveyed to the dead. This shift did not consist simply in a translation from one idiom to another, but through an attempt to fuse the products of his fantasy with scholarship and research through his therapeutic practice.

It is not clear at what point Jung became convinced of survival. From 1929 onwards, a few years after the death of his mother, Jung began to broach this question in public writings.

In his Commentary to the Secret of the Golden Flower, Jung noted that as a physician he attempted to "strengthen the conviction of immortality," especially with older patients. Death, he argued, should be seen as goal, rather than an end, and the latter part of life denoted "life towards death."

Two years later, in his paper "The turning point of life," he elaborated on this theme. The notion of life after death was a primordial image, and hence it made sense to live in accordance with this. From the perspective of a doctor of souls, he argued, it made sense to regard death as only a transition.

Three years later, he wrote his most extended treatment of this theme in his paper, Soul and death. Here he characterized religions as systems for the preparation for death, and argued that it consequently corresponded more to the collective soul of humanity to regard death as the fulfilment of life's meaning.

Belief in an afterlife was anthropologically normative, and it was rather secular materialism that viewed death as a pure cessation that was an aberrant development, viewed from a historical and cross-cultural perspective. The issue of death became particularly acute at midlife. From then, "only those remain living who are willing to die with life. Since what happens in the secret hour of the midday of life is the reversal of the parabola, the birth of death."

Whilst there was no firm proof for the continuation of life after death, parapsychological phenomena, for which there was abundant evidence, pointed to the relativization of space and time, which from an epistemological point of view made the possibility of survival conceivable. In these discussions, one sees psychology and psychotherapy occupying a position previously held by theology and moral philosophy, in trying to articulate an answer to the question of life and death.

This took the form of a new articulation of the authenticity paradigm. Crucially, for Jung, in contrast to figures such as Heidegger, the question of the possibility of survival was central to framing an ethic. In Being and Time, Heidegger argued: "the this-worldly ontological Interpretation of death takes precedence over any ontical otherworldly speculation."

For Jung, as for Myers, one could not reach an adequate "this-worldly" comportment to death without considering the issue of survival.

One reader who took note of Jung's allusion to contemporary physics here was Wolfgang Pauli, who wrote to him after reading his essay. Their collaboration clearly has bearings on the question of postmortem survival, even though this question was not explicitly posed in their correspondence. For the theory of synchronicity was clearly an attempt to render parapsychological phenomena comprehensible in terms of physics, and as such, opened the door to postmortem transcendence.

The notion of the relativization of space and time that Jung was to articulate in his theory of synchronicity could be considered as the basis for an epistemology of survival.

A decade later an event occurred, which Jung described as a "great caesura" in his life and his most tremendous experience. After breaking his foot, he had a heart attack, and experienced a series of visions over a period of several weeks.

He found himself in space, far above Ceylon, he was gazing at Europe, and could also see the Himalayas. He saw a dark block of stone resembling those he had seen in the Bay of Bengal, floating in space. There was an entrance to this, and there was a Hindu inside, who was expecting him. There was an antechamber with small flaming wicks. As he approached, he had the painful experience of earthly experience being stripped from him and yet he felt that everything he had done or experienced remained with him, which gave a sense of poverty and fullness at the same time. He also thought that he was about to enter an illuminated room in which he would meet all the people to whom he belonged and he would know why he had come into being and where his life was leading. However, he then saw the likeness of his doctor come up from the earth, in the form of a king of Kos, the site of the temple of Asclepius, who conveyed the message that there was a protest against him leaving the earth. It took three more weeks before he decided to live again. At one point, he had a vision that he was in the garden of pomegranates, and the wedding of Tifereth and Malchuth was taking place. He was also Rabbi Simon ben Jochai, whose wedding was taking place in the afterlife. Following this, the Marriage of the Lamb took place, and angels were present. He himself was this marriage. Following this, he had a vision of the marriage of Zeus and Hera.

Some elements of these visions seem to stem directly from Jung's preparatory work on Mysterium Coniunctionis.

In an undated letter to Rivkah Scharf, probably written in 1944, Aniela Jaffe thanked her on behalf of Jung:

"Please thank Fraulein Scharf in my name, and tell her that I am especially thankful to her for the Kabbalistic literature that she had got for me before my illness.

It was especially helpful for me in the darkest hours of my illness."

These visions made a great impression on Jung.

In Memories, he recalled that "I would have never imagined that any such experience was possible. It was not a product of imagination. The visions and experiences were utterly real; there was nothing subjective about them: they all had a quality of absolute objectivity."

He described it as a feeling of everlasting bliss. He was particularly struck by the freedom from the burden of the body and from meaninglessness, He described it as the blessedness and wholeness of a non-spatial state, where present, past and future were one. The result of "this knowledge and the vision of the life, death, and the end of all things" was an unconditional affirmation of existence and the courage to write his subsequent books.

Jung's published writings up to that point had been preeminently aimed at a medico-scientific audience, in other words, he tried to convey as much of his conceptions that he felt such readers might be able to grasp, expressed in a suitable exoteric language.

Thus works like Aion, Mysterium Coniunctionis, and Answer to job simply would not have been conceivable prior to this point.

This experience seems to have given Jung complete conviction concerning the survival of bodily death.

In 1947, E. A. Bennet asked Jung about life after death. He records Jung saying: "I am absolutely convinced of personal survival, but I do not know how long it persists. I have an idea that it is ( . ) or months—I get this idea from dreams. My personal experiences are absolutely convincing about survival . . I am absolutely convinced of the survival of the personality—for a time, of the marvelous experience of being dead. I absolutely hated coming back, I did not want to come. It was much better to die—just marvelous and far surpassing any experience I have ever had."

The question of the noetic value of such experiences is a vexed one. Whatever our individual perspectives are, it is clear that Jung considered that he had died and had returned to life.

On February 1, 1945, he wrote of his experience to Kristine Mann:

My illness proved to be a most valuable experience, which gave me the inestimable opportunity of a glimpse behind the veil. The only difficulty is to get rid of the body, to get quite naked and void of the world and the ego-will. When you can give up the crazy will to live and when you seemingly fall into a bottomless mist, then the truly real life begins with everything which you were meant to be and never reached. It is something ineffably grand. I was free, completely free and whole, as I never felt before . . . Death is the hardest thing from the outside and as long as we are outside it. But once inside you taste of such completeness and peace and fulfilment that you don't want to return ... I will not last too long anymore. I am marked. But life has fortunately become provisional. It has become a transitory prejudice, a working hypothesis for the time being but not existence.

This last statement encapsulates a critical shift in Jung's perspective on life, brought about through his experience of death. This relativization of three-dimensional

existence was coupled with an apocalyptic view of the present. On November 2, 1945, Jung wrote to Cary Baynes:

“We have landed indeed, after the nightmare of the war, in the precincts of hell. The war was a long drawn out suspense, in which everything seemed to be still existent yet provisional. One lived from day to day, never certain of to-morrow. An incredible atmosphere of horror was secretly present everywhere. When peace came at last, the immediate of oppression vanished, but only to make room to a feeling of almost cosmic doom. The atomic bomb or at least the thought of such a monstrous menace fitted the picture completely. We are still the island in a sea of abomination and we feel like relics of a faraway Golden Age. It is wonderful that we still can enjoy the beauty of high culture, but we know, that it is a remnant and that it's days are counted.

. Carol Baumann has given me some news about Kristine Mann. I hope that her suffering will soon come to an end. The soul seems to detach from the body pretty early and there seems to be almost no realization of death. What follows is well-nigh incredible. It seems to be an adventure greater and more expected than anything one could dream of. Whatever we do and try in analysis is the first steps towards that goal. That is the only thing, which has accompanied me across the threshold.”

The contrast between the beatific visions and life on earth could not be acute. In the penultimate line here, Jung articulates a critical reformulation of analysis, that follows on from his characterization of religious systems as preparatory systems for death. The whole goal of analysis is conceived here as the preparation for the detachment of the soul from the body. Not how is your life going, but how is your death coming along, would be the critical question from this perspective. Thus analysis became reframed as a modern form of the ars moriendi.

In 1948, in his address at the founding of the Jung Institute in Zurich, one of the topics that Jung singled out for further research was this. He said:

"The investigation of pre- and post-mortal psychic phenomena also come into this category. These are particularly important because of the relativization

of space and time that accompanies them."

Thus Jung was clearly hoping that the newly founded institute would conduct empirical research into this field. In this regard, he would have been disappointed.

As we have seen, by 1944, Jung considered that he had achieved a glimpse behind the veil and experienced death. However, he was less certain about how long this postmortem state persisted.

Jung reflected further on this issue after the death of Toni Wolff in 1953 and Emma Jung in 1955

.

In the published version of Memories, Jung discussed the issue of reincarnation, and noted that:

"Until a few years ago I could not discover anything convincing in this respect, although I kept a sharp lookout for signs. Recently, however, I observed in myself a series of dreams which would seem to describe the process of reincarnation in a deceased person of my acquaintance."

As ever, Jung's discussions in the protocols were more candid: the person in question turns out to be Toni Wolff.

On September 23, 1957, Jung narrated a dream he had had of her to Aniela Jaffe.

In the dream, she had returned to life, as if there had been a type of misunderstanding that she had died, and she had returned to live a further part of her life. Aniela Jaffe asked Jung if he thought this could indicate a possible.. . who are the dead, and what does it mean to answer them?

Rebirth. Jung replied that with his wife he had a sense of a great detachment or distance. By contrast, he felt that Toni Wolff was close. Jaffé then asked him whether something that one has not completed in one life has to be continued in a next life.

Jung replied that his wife reached something that Toni Wolff didn't reach and that rebirth would constitute a terrible increase of actuality for her. He had the impression that Toni Wolff was nearer the earth, that she could manifest herself better to him, whilst his wife was on another level where he couldn't reach her. He concluded that Toni Wolff was in the neighborhood, that she was nearer the sphere of three dimensional existence, and hence had the chance to come into existence again, He had the impression that for her a continuation of three dimensional existence would not be meaningless. He felt that higher insight hindered the wish for re-embodiment.

As to the status of such metaphysical conceptions such as rebirth, he appealed to pragmatic rule, stating that one should judge the truth of such conceptions by seeing whether they had a healing or stimulating effect.

Finally, we come to the question, who are the dead, and what does it mean to answer them?

On June 13, 1958, Jung discussed this issue with Aniela Jaffe. He noted. that one could only find one's myth if one was together with one's dead. He felt that he had given answers to his dead, and had relieved himself of the burden of this responsibility. However, his answers were applicable to his dead.

There was a danger that others would repeat this parrot-fashion to avoid answering their own dead. The question of whether the dead were spiritual or corporeal ancestors was unclear.

In another sense, Freud had left him an inheritance, a question directed towards him, which he had tried to take further. There are several striking things in this discussion.

First, Jung indicates that his finding his myth could only take place in conjunction with his dead.

In this regard, his theology of the dead forms an essential component of his myth and the recuperation of meaning. He draws attention to the fact that the answers that he has provided to his dead, in the form of his work, may not at all be suitable for anyone else's dead, and hence in the elaboration of their myths. Indeed, there is a danger that they would simply borrow his to avoid the difficulty of articulating answers to their own dead.

Finally, there is the question of the identity of the dead. Are Jung's ancestors simply the previous generations of his family, his spiritual ancestry, such as Kant, Goethe, Nietzsche, and Swedenborg, or former associates such as Freud?

This issue of the identity of one's ancestors and the questions that they posed was linked to the question of karma. In this regard, he was particularly interested in Buddhist conceptions of karma. In Memories, he reflected:

“Am I a combination of the lives of these ancestors and I do embody these lives again? Have I lived before as a specific personality, and I progress so far in that life that I am now able to seek a solution? I do not know. Buddha left the question open, and I like to assume that he himself did not know with certainty ... It might happen that I would not need to be reborn again so long as the world needed no such answer, and that I would be entitled to several hundred years of peace until someone was once more needed who took an interest in these matters and could profitably tackle the task anew. I imagine that for a while a period of rest could ensue, until the stint I had done in my lifetime needed to be taken up again.

One may pose the question, how are we dealing with the questions that Jung posed and left unanswered?

If he is still around, is his continued development dependent on us? Whatever one's own perspective on these questions may be, it is clear that we have yet to catch up with his work and understand its historical genesis, and that it is our task to safeguard this inheritance. This reconstruction of his thinking around life and death is one contribution to this end. ~”The Boundless Expanse: Jung’s Reflections on Death and Life” by Sonu Shamdasani

by Sonu Shamdasani

Jung's lectures before the Zofingia society also provide indication of his first formulations of the concept of life and his clear commitment to vitalism.

It was clear to him at this time that a positive definition of an irreducible life force was essential for postmortem existence in any form to be conceivable.

As I've traced in detail elsewhere, throughout his career, Jung remained committed to a position that could broadly be described as neo-vitalist.

Thus works such as Jung's 1928 paper on the "energetics of the soul," which at first glance appear to be far removed from such questions have a critical bearing on them, in laying the basis for an ontology in which survival is at least theoretically conceivable.

For example in 1930, he wrote to Alice Raphael:

... Bergson is quite right when he thinks of the possibility of relatively loose connection between the brain and consciousness, because despite of our ordinary experience the connection might be less tight than we suppose. There is no reason why one shouldn't suppose that consciousness could exist detached from a brain . . . the real difficulty

begins ... when you should prove that there is consciousness without a brain. It would amount to the hitherto unproven fact of an evidence that there are ghosts. I think that this is the most difficult thing in the world to create an evidence in that respect entirely satisfactory from a scientific point of view . How can one establish an indisputable evidence of a consciousness without a brain? I might be satisfied if such a consciousness would be able to write an intelligent book, invent new apparatuses, provide us with new information that couldn't possibly be found in human brains, and if it were evident that there would be no high power medium among the spectators. But such a thing is quite unthinkable ... Trance conditions are certainly very interesting and I know a good deal about them—though never enough. But they wouldn't yield any strict evidence, because they are conditions of a living brain.

Consciousness detached from the brain? Nothing could be further from the current fad for neuro-scientific reductionism.

In retrospect Jung recalled that a pivotal experience in his understanding of the relations between the living and the dead was a dream that occurred whilst he was at work on his book, Transformations and Symbols of the Libido. In the autumn of 1910, he undertook a bicycle tour in Northern Italy and was staying in Arona:

In the dream I was in an assemblage of distinguished spirits of earlier centuries;' the feeling was similar to the one I had later towards the 'illustrious ancestors' in the black rock temple of my 1944 vision.

The conversation was conducted in Latin. A gentleman with a long, curly wig addressed me and asked a difficult question, the gist of which I could no longer recall after I woke up. I understood him, but did not have a sufficient command of the language to answer him in Latin.

I felt so profoundly humiliated by this that the emotion awakened me. At the very moment of awakening I thought of the book I was then working on, Transformations and Symbols of the Libido, and had such inferiority feelings about the unanswered question that I immediately took the train home in order to get back to work ... I had to work, to find the question.

Not until years later did I understand the dream and my reaction. The bewigged gentleman was a kind of ancestral spirit or spirit of the dead, who had addressed questions to me—in vain! It was still too soon, I had not yet come so far, but I had an obscure feeling that by working on my book I would be answering the question that had been asked. It had been asked by, as it were, my spiritual forefathers, in the hope and expectation that they would learn what they had not been able to find out during their time on earth, since the answer had first to be created in the centuries that followed.

Here, Jung indicates that his first task was to attempt to reconstruct the question that had been posed to him, and that the manner in which he did this was to continue working on his book. In this connection it seems important that one central problematic in this work was actually the question of inheritance: our relation to the past and its continued relevance in the present.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, a number of figures became interested in organic or ancestral memory, a notion buttressed by Lamarckian views on inheritance and Ernst Haeckel's biogenic law, the contention that the individual developed recapitulated the development of the species. Figures such as Thomas Laycock, Théodule Ribot, and Stanley Hall contended that many of our actions and reactions should be viewed as ancestral reversions, and denoted the activation of mnemonic residues laid down in the course of human evolution, and that such residues resided in a phylogenetic layer of the unconscious.

As Gustave Le Bon noted in 1894, "Infinitely more numerous than the living, the dead are also infinitely more powerful than them. They govern the immense domain of the unconscious, this invisible domain which contains under its empire all the manifestations of intelligence and character."

As I've reconstructed elsewhere, the views of the organic memory theories became a constitutive element of Jung's theory formation in Transformations and Symbols of the Libido. As Jung put it, "The soul possesses in some degree a historical stratification, whereby the oldest stratum of which would correspond to the unconscious"

It is not clear whether the bewigged gentleman would have been satisfied with a lecture on phylogenetic psychology, or that he would have followed all the twists and turns of Jung's argument in this work, tracing the myriad transformations of the chameleon-like ever-present libido, which not a few of the living have had a hard time with. However, it is clear that Jung himself was not satisfied with the answers he had given in this work. As he recounted, soon after the completion of the work, a more serious question arose, to which he could not give an answer at that time, namely, what was his myth.

This question lay at the heart of Jung's confrontation with the unconscious. Perhaps it would not be going too far to say that this question may have lain closer to the one which may have been posed by the bewigged gentleman, Viewed from this perspective, Jung's self-exploration can be seen as his attempt to articulate an answer.

Further light on these connections may be shed by a consideration of Jung's Septem Sermones ad Mortuos, written in 1916. Until now, the Septem Sermones has remained the one significant chapter of what I term Jung's private cosmology that has been published. With the publication of Jung's Red Book, the study of his private cosmology as well as its interplay with his scholarly writings will finally be able to commence.

Till then, there still remains much to be studied in the Sermones. To begin with, they shed important light on what could be termed Jung's theology of the dead.

First, we should retrace their genesis. At the beginning of 1916, Jung experienced a striking series of parapsychological events in his house. In Memories, Jung recounted what followed:

Around five o'clock in the afternoon on Sunday the front-door bell began ringing frantically. It was a bright summer day; the two maids were in the kitchen, from which the open square outside the front door could be seen. Everyone immediately looked to see who was there, but there was no one in sight. I was sitting near the door bell, and not heard it but saw it moving. We all simply stared at one another. The atmosphere was thick, believe me! Then I knew something had to happen. The whole house was as if there was a crowd present, crammed full of spirits. They were packed deep right up to the door and the air was so thick it was scarcely possible to breathe. As for myself, I was all a-quiver with the question: "For God's sake, what in the world is this?" Then they cried out in chorus, "We have come back from Jerusalem where we found not what we sought." That is the beginning of the Septem Sermones. Then it began to flow out of me, and in the course of three evenings the thing was written. As soon as I took up the pen, the whole ghastly assemblage evaporated. The room quieted and the atmosphere cleared. The haunting was over."

The Sermones commence with the following lines: "The dead came back from Jerusalem, where they did not find what they sought, They requested entrance with me and wanted to learn with me, so I taught them."

In the course of their interchange, the dead posed a number of questions to Jung. "We want to know of God. Where is God? Is God dead?" "Speak to us again about the highest God." "Speak to us of gods and devils, cursed one." "Teach us, fool, of the church and holy communion." "There is still one thing which we forgot to say—teach us about man."

In replying to these questions posed by the dead, Jung articulated a comprehensive psycho-theological cosmology. However, initially at least, the dead were apparently unsatisfied with Jung's teaching:

"The dead disappeared grumbling and moaning and their cries died away in the distance." "The dead now raised a great tumult, for they were Christians." "Now the dead howled and raged, for they were unperfected." What do their questions tell us about them?

These "unperfected" Christian dead apparently did not know whether God was alive or dead, as if the perturbations of the teachings of Nietzsche's Zarathustra had reached the beyond; they appeared to be of a polytheistic disposition and were ignorant of the church and knew not of man.

If, like Socrates, these dead had sought to have their questions answered by those already dead, they appear to have been disappointed, and have had no recourse but to turn to the living.

At first glance, this scene provides a striking reversal of what is usually found in spiritualism and its literature, where the living seek and receive instruction from the dead.

Whilst quite struck by this, Jung did not consider it exceptional.

To Aniela Jaffe, he noted that it astonished him that the dead had posed him questions, as one assumes that the dead had greater knowledge than us. It seemed that the dead only knew what they knew when they died, hence their tendency to intrude into our lives.

In this regard he found the Chinese custom that events should be conveyed to the ancestors to be very significant.

It seemed to him that personal development did not stop at death, but was dependent upon the increase of consciousness among the living. Spiritualistic literature indicated that the dead really sought psychological insight.

Unlike his dream at Arona, Jung here was able to note the questions of dead and to reply with detailed answers.

This passage articulates a critical aspect of Jung's private cosmology:

“What is vital here is not just a conviction of the survival of bodily death, but a view of the significance of human life, conceived as a process of the development of consciousness that does not stop at the grave—moreover, a process in which the further development of the dead is dependent on the increase of consciousness of the living. Within this conception, through our terrestrial development, we are in fact aiding the postmortem development of the dead.

The Septem Sermones do not merely articulate a private cosmology. To Aniela Jaffé, Jung commented that they formed a prelude to what he would later communicate to the world in his books. Hence the task was one of conveying to the living what he had already conveyed to the dead. This shift did not consist simply in a translation from one idiom to another, but through an attempt to fuse the products of his fantasy with scholarship and research through his therapeutic practice.

It is not clear at what point Jung became convinced of survival. From 1929 onwards, a few years after the death of his mother, Jung began to broach this question in public writings.

In his Commentary to the Secret of the Golden Flower, Jung noted that as a physician he attempted to "strengthen the conviction of immortality," especially with older patients. Death, he argued, should be seen as goal, rather than an end, and the latter part of life denoted "life towards death."

Two years later, in his paper "The turning point of life," he elaborated on this theme. The notion of life after death was a primordial image, and hence it made sense to live in accordance with this. From the perspective of a doctor of souls, he argued, it made sense to regard death as only a transition.