Archetypes

Archetypes Are Our Eternal Ancestors

Thus the archetype as a phenomenon is conditioned by place and time, but on the other hand it is an invisible structural pattern independent of place and time, and like the instincts proves to be an essential component of the psyche.

~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Pages 538-539.

If I say that we do not know "the ultimate derivation of the archetype," I mean that we are unable to observe and describe the archetype in its unconscious condition. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 372-373

As we do not know the actual status of an archetype in the unconscious and only know it in that form in which it becomes conscious, it is impossible to describe the human archetype and to compare it to an animal archetype. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 372-373

But the supreme meaning is the path the way and the bridge to what is to come.

That is the God yet to come.

It is not the coming God himself but his image which appears in the supreme meaning.

God is an image, and those who worship him must worship him in the images of the supreme meaning.

The supreme meaning is not a meaning and not an absurdity, it is image and force in one, magnificence and force together.

The supreme meaning is the beginning and the end.

It is the bridge of going across and fulfillment.

--Carl Jung, The Red Book, Pages 229-230.

This, too, is an expression of something that has always claimed my deepest interest and my greatest attention: the manifestation of archetypes, or archetypal forms, in all the phenomena of life: in biology, physics, history, folklore, and art, in theology and mythology, in parapsychology, as well as in the symptoms of insane patients and neurotics, and finally in the dreams and life of every individual man and woman.

The intimation of forms hovering in a background not in itself knowable gives life the depth which, it seems to me, makes it worth living. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 396-397

Or in other words: there is no outside to the collective psyche. In our ordinary mind we are in the worlds of time and space and within the separate individual psyche. In the state of the archetype we are in the collective psyche, in a world-system whose space-time categories are relatively or absolutely abolished. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 398-400

t is a structural element of the psyche we find everywhere and at all times; and it is that in which all individual psyches are identical with each other, and where they function as if they were the one undivided psyche the ancients called anima mundi or the psyche toukosmou. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 398-400

We conclude therefore that we have to expect a factor in the psyche that is not subject to the laws of time and space, as it is on the contrary capable of suppressing them to a certain extent. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 398-400

Concerning archetypes, migration and verbal transmission are self-evident, except in those cases where individuals reproduce archetypal forms outside of all possible external influences (good examples in childhood dreams!). ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 450-451

The 'absolute knowledge' which is characteristic of synchronistic phenomena, a knowledge not mediated by the sense organs, supports the hypothesis of a self-subsistent meaning, or even expresses its existence. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 445-449

Reification (also known as concretism, hypostatization, or the fallacy of misplaced concreteness) is a fallacy of ambiguity, when an abstraction (abstract belief or hypothetical construct) is treated as if it were a concrete, real event, or physical entity. [1][2] In other words, it is the error of treating something which is not concrete, such as an idea, as a concrete thing . A common case of reification is the confusion of a model with reality. Mathematical or simulation models may help understand a system or situation, but they model an abstract and simple mental image, not real life (which will also differ from the model): "the map is not the territory". Reification is part of normal usage of natural language (just like metonymy for instance), as well as of literature, where a reified abstraction is intended as a figure of speech, and actually understood as such. But the use of reification in logical reasoning or rhetoric is misleading and usually regarded as a fallacy.

Emotions follow an instinctual pattern, i.e., an archetype. ~ Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 43-47.

Where an archetype prevails, we can expect synchronistic phenomena, i.e., acausal correspondences, which consist in a parallel arrangement of facts in time. The arrangement is not the effect of a cause. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 43-47.

It looks as if the collective character of the archetypes would manifest itself also in meaningful coincidences, i.e., as if the archetype (or the collective unconscious) were not only inside the individual, but also outside, viz. in one's environment, as if sender and percipient were in the same psychic space, or in the same time (in precognition cases).

~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 43-47.

Just as the physicist regards the atom as a model, I regard archetypal ideas as sketches for the purpose of visualizing the unknown background. --C.G. Jung ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 64-65.

No doubt the archetypes are present everywhere, but there is also a widespread resistance to this "mythology." That is why even the gospel has to be "demythologized." ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 83-86.

Divine favour and daemonic evil or danger are archetypal.

The self is transcendental and is only partially conscious.

Empirically it is good and evil.

~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 52-53.

My God-image corresponds to an autonomous archetypal pattern.

Therefore I can experience God as if he were an object, but I need not assume that it is the only image. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 151-154.

Nobody would assume that the biological pattern is a philosophical assumption like the Platonic idea or a Gnostic hypostasis. The same is true of the archetype. Its autonomy is an observable fact and not a philosophical hypostasis. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 151-154.

With increasing approximation to the centre there is a corresponding depotentiation of the ego in favour of the influence of the "empty" centre, which is certainly not identical with the archetype but is the thing the archetype points to. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

I don't know whether the archetype is "true" or not. I only know that it lives and that I have not made it. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

"God" in this sense is a biological, instinctual and elemental "model," an archetypal "arrangement" of individual, contemporary and historical contents, which, despite its numinosity, is and must be exposed to intellectual and moral criticism, just like the image of the "evolving" God or of Yahweh or the Summum Bonum or the Trinity. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 254-256.

On the other hand "God" is a verbal image, a predicate or mythologem founded on archetypal premises which underlie the structure of the psyche as images of the instincts ("instinctual patterns"). ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 254-256.

I have in all conscience never supposed that in discussing the psychic structure of the God-image I have taken God himself in hand. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

All statements about and beyond the "ultimate" are anthropomorphisms and, if anyone should think that when he says "God" he has also predicated God, he is endowing his words with magical power. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

The up surging archetypal material is the stuff of which mental illnesses are made. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

For me "God" is on the one hand a mystery that cannot be unveiled, and to which I must attribute only one quality: that it exists in the form of a particular psychic event which I feel to be numinous and cannot trace back to any sufficient cause lying within my field of experience. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 254-256.

As the Chinese would say, the archetype is only the name of Tao, not Tao itself. Just as the Jesuits translated Tao as "God," so we can describe the "emptiness" of the centre as "God."

Emptiness in this sense doesn't mean "absence" or "vacancy," but something unknowable which is endowed with the highest intensity. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

As a young man I drew the conclusion that you must obviously fulfill your destiny in order to get to the point where a donum gratiae might happen along. But I was far from certain, and always kept the possibility in mind that on this road I might end up in a black hole. I have remained true to this attitude all my life. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-258.

The archetype itself (nota bene not the archetypal representation!) is psychoid,i.e., transcendental and thus relatively beyond the categories of number, space, and time. That means, it approximates to oneness and immutability. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 317-319.

So far as the integration of personality components are concerned, it must be borne in mind that the ego-personality as such does not include the archetypes but is only influenced by them; for the archetypes are universal and belong to the collective psyche over which the ego has no control. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 341-343.

Emotions follow an instinctual pattern, i.e., an archetype. ~ Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 43-47.

Where an archetype prevails, we can expect synchronistic phenomena, i.e., acausal correspondences, which consist in a parallel arrangement of facts in time. The arrangement is not the effect of a cause. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 43-47.

It looks as if the collective character of the archetypes would manifest itself also in meaningful coincidences, i.e., as if the archetype (or the collective unconscious) were not only inside the individual, but also outside, viz. in one's environment, as if sender and percipient were in the same psychic space, or in the same time (in precognition cases).

~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 43-47.

Just as the physicist regards the atom as a model, I regard archetypal ideas as sketches for the purpose of visualizing the unknown background. --C.G. Jung ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 64-65.

No doubt the archetypes are present everywhere, but there is also a widespread resistance to this "mythology." That is why even the gospel has to be "demythologized." ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 83-86.

Divine favour and daemonic evil or danger are archetypal.

The self is transcendental and is only partially conscious.

Empirically it is good and evil.

~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 52-53.

My God-image corresponds to an autonomous archetypal pattern.

Therefore I can experience God as if he were an object, but I need not assume that it is the only image. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 151-154.

Nobody would assume that the biological pattern is a philosophical assumption like the Platonic idea or a Gnostic hypostasis. The same is true of the archetype. Its autonomy is an observable fact and not a philosophical hypostasis. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 151-154.

With increasing approximation to the centre there is a corresponding depotentiation of the ego in favour of the influence of the "empty" centre, which is certainly not identical with the archetype but is the thing the archetype points to. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

I don't know whether the archetype is "true" or not. I only know that it lives and that I have not made it. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

"God" in this sense is a biological, instinctual and elemental "model," an archetypal "arrangement" of individual, contemporary and historical contents, which, despite its numinosity, is and must be exposed to intellectual and moral criticism, just like the image of the "evolving" God or of Yahweh or the Summum Bonum or the Trinity. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 254-256.

On the other hand "God" is a verbal image, a predicate or mythologem founded on archetypal premises which underlie the structure of the psyche as images of the instincts ("instinctual patterns"). ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 254-256.

I have in all conscience never supposed that in discussing the psychic structure of the God-image I have taken God himself in hand. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

All statements about and beyond the "ultimate" are anthropomorphisms and, if anyone should think that when he says "God" he has also predicated God, he is endowing his words with magical power. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

The up surging archetypal material is the stuff of which mental illnesses are made. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

For me "God" is on the one hand a mystery that cannot be unveiled, and to which I must attribute only one quality: that it exists in the form of a particular psychic event which I feel to be numinous and cannot trace back to any sufficient cause lying within my field of experience. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 254-256.

As the Chinese would say, the archetype is only the name of Tao, not Tao itself. Just as the Jesuits translated Tao as "God," so we can describe the "emptiness" of the centre as "God."

Emptiness in this sense doesn't mean "absence" or "vacancy," but something unknowable which is endowed with the highest intensity. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

As a young man I drew the conclusion that you must obviously fulfill your destiny in order to get to the point where a donum gratiae might happen along. But I was far from certain, and always kept the possibility in mind that on this road I might end up in a black hole. I have remained true to this attitude all my life. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-258.

The archetype itself (nota bene not the archetypal representation!) is psychoid,i.e., transcendental and thus relatively beyond the categories of number, space, and time. That means, it approximates to oneness and immutability. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 317-319.

So far as the integration of personality components are concerned, it must be borne in mind that the ego-personality as such does not include the archetypes but is only influenced by them; for the archetypes are universal and belong to the collective psyche over which the ego has no control. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 341-343.

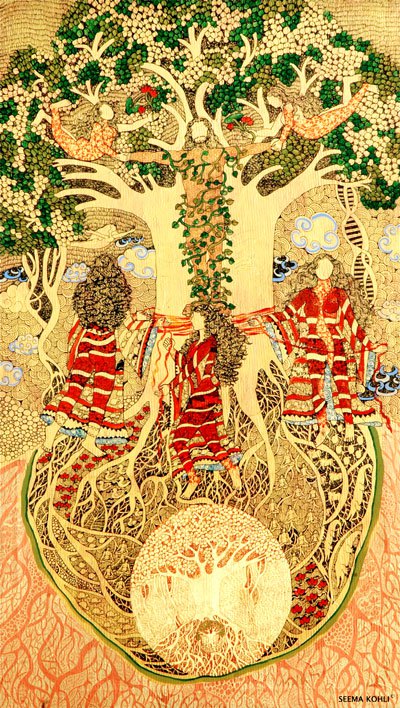

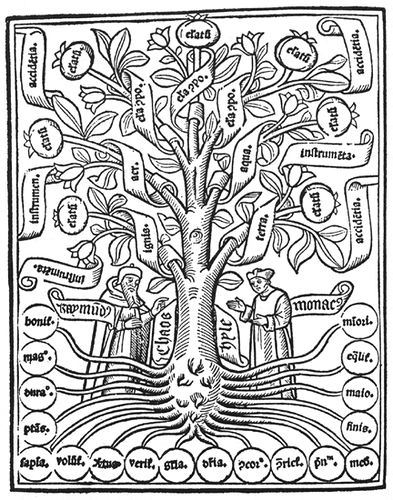

"One is the beginning, the Sun God.

"Two is Eros, for he binds two together and spreads himself out in brightness.

"Three is the Tree of Life, for it fills space with bodies.

"Four is the devil, for he opens all that is closed. He dissolves everything formed and physical; he is the destroyer in whom everything becomes nothing.

~Diahmon, Liber Novus, 351.

I would like to suggest that every psychic reaction which is out of proportion to its precipitating cause should be investigated as to whether it may be conditioned at the same time by an archetype. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 32.

Phylogenetically as well as ontogenetically we have grown up out of the dark confines of the earth; hence the factors that affected us most close*ly became archetypes, and it is these primordial images which influence us most directly, and therefore seem to be the most powerful. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 32.

We shall have to reckon with quite unusual difficulties in dealing with it, and the first of these is that the archetype and its function must be understood far more as a part of man's prehistoric, irrational psychology than as a rationally conceivable system. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 31.

Archetypes are systems of readiness for action, and at the same time images and emotions. They are inherited with the brain structure—indeed, they are its psychic aspect. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 31

I tried to give a general view of the structure of the unconscious. Its contents, the archetypes, are as it were the hidden foundations of the conscious mind, or, to use another comparison, the roots which the psyche has sunk not only in the earth in the narrower sense but in the world in general. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 31.

We should make the archetype responsible only for a definite, minimal, normal degree of fear; any pronounced increase, felt to be abnormal, must have special causes. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 33.

As the Chinese would say, the archetype is only the name of Tao, not Tao itself. Just as the Jesuits translated Tao as "God," so we can describe the "emptiness" of the center as "god." ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 258-259.

We simply do not know the ultimate derivation of the archetype any more than

we know the origin of the psyche. ~Carl Jung, CW 12, Page 14.

The archetypes are complementary and equivalents of the "outside" world and therefore possess "cosmic" character. Thins explains their numinosity and godlikeness. ~Carl Jung, CW 9, Page 196.

The archetype is an irrepresentable factor, a "disposition" which starts functioning at a given moment in the development of the human mind and arranges the material of consciousness in definite patterns. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Page 148.

We must, however, constantly bear in mind that what we mean by "archetype" is in itself irrepresentable, but has effects which make visualization of it possible, namely the archetypal images and ideas. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Page 214.

I have landed in the Eastern sphere through the waters of the unconscious, for the truths of the unconscious can never be thought up, they can be reached only by following a path which all cultures right down to the most primitive level have called the way of initiation. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Page 87.

We must, however, constantly bear in mind that what we mean by "archetype" is in itself irrepresentable, but has effects which make visualization of it possible, namely the archetypal images and ideas. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Page 214.

When an archetype is constellated it can appear in the inner and the outer world at the same time. Each distinct case is an example of creation. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Page 55.

When an archetypal event approaches the sphere of consciousness, it also manifests itself in the outer life. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Page 55.

A woman is more likely to acknowledge her own duality. A man is continually blinded by his intellect and does not learn through insight. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Page 51.

If a primordial image forces itself onto consciousness, we have to fill it with as much substance as possible to grasp the whole scope of its meaning. ~Carl Jung, Children’s Dreams Seminar, Page 368.

When I say as a psychologist , that God is an archetype, I mean by that the "type" in the psyche. ~Carl Jung, CW 12, Page 14.

You see, the archetype is a force. It has an autonomy, and it can suddenly seize you. It is like a seizure. ~Carl Jung, Evans Conversations, Page 17.

Another way is they tell them all of the things they should not do, like the Decalogue, "Thou shalt not," and that is always supported by mythological tales.

That, of course, gave me a motive to study the archetypes, because I began to see that the structure of what I then called the collective

unconscious was really a sort of agglomeration of such typical images, each of which had a unique quality.

The archetypes are, at the same time, dynamic.

They are instinctual images that are not intellectually invented.

They are always there and they produce certain processes in the unconscious that one could best compare with myths.

That's the origin of mythology.

Mythology is a pronouncing of a series of images that formulate the life of archetypes.

So the statements of every religion, of many poets, etc., are statements about the inner mythological process, which is a necessity because man is not complete if he is not conscious of that aspect of things.

For instance, our ancestors have done so and so, and so shall you do.

Or such and such a hero has done so and so, and that is your model.

~Carl Jung, Evans Conversations, Pages 16-18.

It is quite certain, however, that man is born with a certain functioning, a certain way of functioning, a certain pattern of behavior which is expressed in the form of archetypal images, or archetypal forms. ~Carl Jung, Evans Conversations, Page 16.

It [The Mandala] is the archetype of inner order; and it is always used in that sense, either to make arrangements of the many, many aspects of the universe, a world scheme, or to arrange the complicated aspects of our psyche into a scheme. ~Jung, Evans Conversations, Page 21.

Primeval history is the story of the beginning of consciousness by differentiation from the archetypes. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Page 32

It is a great mistake in practice to treat an archetype as if it were a mere name, word, or concept. It is far more than that: it is a piece of life, an image connected with the living individual by the bridge of emotion. ~Carl Jung, Man and His Symbols, Page 96.

You see, the archetype is a force. It has an autonomy, and it can suddenly seize you. It is like a seizure. ~Carl Jung, Evans Conversations, Page 17

On account of its transcendence, the a archetype per se is as irrepresentable as the nature of light and hence must be strictly distinguished from the archetypal idea or mythologem (see "Der Geist der Psychologie" in Eranos-Jahrbuch 1946 ).

C.G. Jung ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 21-23.

Archetypes are not mere concepts but are entities, exactly like whole numbers, which are not merely aids to counting but possess irrational qualities that do not result from the concept of counting, as for instance the prime numbers and their behaviour. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 22.

When I say "atom" I am talking of the model made of it; when I say "archetype" I am talking of ideas corresponding to it, but never of the thing-in itself, which in both cases is a transcendental mystery. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 53-55.

Nobody has ever seen an archetype, and nobody has ever seen an atom either.

~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 53-55.

So the identity with the body is one of the first things which makes an ego; it is the spatial separateness that induces, apparently, the concept of an ego. ~Carl Jung, Evans Conversations, Page 15.

Nobody would assume that the biological pattern is a philosophical assumption like the Platonic idea or a Gnostic hypostasis. The same is true of the archetype. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 152.

One must therefore assume that the effective archetypal ideas, including our model of the archetype, rest on something actual even though unknowable, just as the model of the atom rests on certain unknowable qualities of matter. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 53-55.

"Two is Eros, for he binds two together and spreads himself out in brightness.

"Three is the Tree of Life, for it fills space with bodies.

"Four is the devil, for he opens all that is closed. He dissolves everything formed and physical; he is the destroyer in whom everything becomes nothing.

~Diahmon, Liber Novus, 351.

I would like to suggest that every psychic reaction which is out of proportion to its precipitating cause should be investigated as to whether it may be conditioned at the same time by an archetype. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 32.

Phylogenetically as well as ontogenetically we have grown up out of the dark confines of the earth; hence the factors that affected us most close*ly became archetypes, and it is these primordial images which influence us most directly, and therefore seem to be the most powerful. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 32.

We shall have to reckon with quite unusual difficulties in dealing with it, and the first of these is that the archetype and its function must be understood far more as a part of man's prehistoric, irrational psychology than as a rationally conceivable system. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 31.

Archetypes are systems of readiness for action, and at the same time images and emotions. They are inherited with the brain structure—indeed, they are its psychic aspect. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 31

I tried to give a general view of the structure of the unconscious. Its contents, the archetypes, are as it were the hidden foundations of the conscious mind, or, to use another comparison, the roots which the psyche has sunk not only in the earth in the narrower sense but in the world in general. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 31.

We should make the archetype responsible only for a definite, minimal, normal degree of fear; any pronounced increase, felt to be abnormal, must have special causes. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Page 33.

As the Chinese would say, the archetype is only the name of Tao, not Tao itself. Just as the Jesuits translated Tao as "God," so we can describe the "emptiness" of the center as "god." ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 258-259.

We simply do not know the ultimate derivation of the archetype any more than

we know the origin of the psyche. ~Carl Jung, CW 12, Page 14.

The archetypes are complementary and equivalents of the "outside" world and therefore possess "cosmic" character. Thins explains their numinosity and godlikeness. ~Carl Jung, CW 9, Page 196.

The archetype is an irrepresentable factor, a "disposition" which starts functioning at a given moment in the development of the human mind and arranges the material of consciousness in definite patterns. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Page 148.

We must, however, constantly bear in mind that what we mean by "archetype" is in itself irrepresentable, but has effects which make visualization of it possible, namely the archetypal images and ideas. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Page 214.

I have landed in the Eastern sphere through the waters of the unconscious, for the truths of the unconscious can never be thought up, they can be reached only by following a path which all cultures right down to the most primitive level have called the way of initiation. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Page 87.

We must, however, constantly bear in mind that what we mean by "archetype" is in itself irrepresentable, but has effects which make visualization of it possible, namely the archetypal images and ideas. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Page 214.

When an archetype is constellated it can appear in the inner and the outer world at the same time. Each distinct case is an example of creation. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Page 55.

When an archetypal event approaches the sphere of consciousness, it also manifests itself in the outer life. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Page 55.

A woman is more likely to acknowledge her own duality. A man is continually blinded by his intellect and does not learn through insight. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Page 51.

If a primordial image forces itself onto consciousness, we have to fill it with as much substance as possible to grasp the whole scope of its meaning. ~Carl Jung, Children’s Dreams Seminar, Page 368.

When I say as a psychologist , that God is an archetype, I mean by that the "type" in the psyche. ~Carl Jung, CW 12, Page 14.

You see, the archetype is a force. It has an autonomy, and it can suddenly seize you. It is like a seizure. ~Carl Jung, Evans Conversations, Page 17.

Another way is they tell them all of the things they should not do, like the Decalogue, "Thou shalt not," and that is always supported by mythological tales.

That, of course, gave me a motive to study the archetypes, because I began to see that the structure of what I then called the collective

unconscious was really a sort of agglomeration of such typical images, each of which had a unique quality.

The archetypes are, at the same time, dynamic.

They are instinctual images that are not intellectually invented.

They are always there and they produce certain processes in the unconscious that one could best compare with myths.

That's the origin of mythology.

Mythology is a pronouncing of a series of images that formulate the life of archetypes.

So the statements of every religion, of many poets, etc., are statements about the inner mythological process, which is a necessity because man is not complete if he is not conscious of that aspect of things.

For instance, our ancestors have done so and so, and so shall you do.

Or such and such a hero has done so and so, and that is your model.

~Carl Jung, Evans Conversations, Pages 16-18.

It is quite certain, however, that man is born with a certain functioning, a certain way of functioning, a certain pattern of behavior which is expressed in the form of archetypal images, or archetypal forms. ~Carl Jung, Evans Conversations, Page 16.

It [The Mandala] is the archetype of inner order; and it is always used in that sense, either to make arrangements of the many, many aspects of the universe, a world scheme, or to arrange the complicated aspects of our psyche into a scheme. ~Jung, Evans Conversations, Page 21.

Primeval history is the story of the beginning of consciousness by differentiation from the archetypes. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Page 32

It is a great mistake in practice to treat an archetype as if it were a mere name, word, or concept. It is far more than that: it is a piece of life, an image connected with the living individual by the bridge of emotion. ~Carl Jung, Man and His Symbols, Page 96.

You see, the archetype is a force. It has an autonomy, and it can suddenly seize you. It is like a seizure. ~Carl Jung, Evans Conversations, Page 17

On account of its transcendence, the a archetype per se is as irrepresentable as the nature of light and hence must be strictly distinguished from the archetypal idea or mythologem (see "Der Geist der Psychologie" in Eranos-Jahrbuch 1946 ).

C.G. Jung ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 21-23.

Archetypes are not mere concepts but are entities, exactly like whole numbers, which are not merely aids to counting but possess irrational qualities that do not result from the concept of counting, as for instance the prime numbers and their behaviour. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 22.

When I say "atom" I am talking of the model made of it; when I say "archetype" I am talking of ideas corresponding to it, but never of the thing-in itself, which in both cases is a transcendental mystery. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 53-55.

Nobody has ever seen an archetype, and nobody has ever seen an atom either.

~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 53-55.

So the identity with the body is one of the first things which makes an ego; it is the spatial separateness that induces, apparently, the concept of an ego. ~Carl Jung, Evans Conversations, Page 15.

Nobody would assume that the biological pattern is a philosophical assumption like the Platonic idea or a Gnostic hypostasis. The same is true of the archetype. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 152.

One must therefore assume that the effective archetypal ideas, including our model of the archetype, rest on something actual even though unknowable, just as the model of the atom rests on certain unknowable qualities of matter. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 53-55.

archetype (n.) "original pattern from which copies are made," 1540s [Barnhart] or c.1600 [OED], from Latin archetypum, from Greek arkhetypon "pattern, model, figure on a seal," neuter of adjective arkhetypos "first-moulded," from arkhe- "first" (see archon) + typos "model, type, blow, mark of a blow" (see type). Jungian psychology sense of "pervasive idea or image from the collective unconscious" is from 1919. Jung defined archetypal images as "forms or images of a collective nature which occur practically all over the earth as constituents of myths and at the same time as autochthonous individual products of unconscious origin." ["Psychology and Religion" 1937]

Often when people behave in an exceedingly unexpected manner the appearance of an archetype is the explanation ; archetypes go back not only through human history, but to our ancestors the animals, that is why we are able to understand animals so well and make friends with them. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lectures, Vol. 2, Page 177.

The moment where the archetype appears is always characterized by remarkable emotion; it, as it were, fascinates the dreamer and exalts him, as if the Muse had kissed him not only on the forehead but on the shoulder. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 177.

It is when we come to a summit in life that the archetypal symbols appear. These primeval pictures of human life form the collective unconscious. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Pages 176-177.

It is also a plausible hypothesis that the archetype is produced by the original life urge and then gradually grows up into consciousness-with the qualification, however, that the innermost essence of the archetype can never become wholly conscious, since it is beyond the power of imagination and language to grasp and express its deepest nature. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Page 313.

When all the archetypal images are properly placed in a hierarchy, when that which must be below is below, and that which must be above is above, our final condition can recapture our original blissful state.

Archetypes are images in the soul that represent the course of one's life.

One part of the archetypal content is of material and the other of spiritual origin.

The more an archetype is amplified the more understandable it becomes.

It is hard to explain because the spiritual cannot be expressed in a few words.

The archetype signifies that particular spiritual reality which cannot be attained unless life is lived in consciousness.

Archetypes are not matters of faith; we can know that they are there.

An archetype is composed of an instinctual factor and a spiritual image.

The approaches to it from the instinctual or the spiritual side are very different.

The libido cannot be freed, however, unless the archetypal images can be made conscious.

When fantasy pictures are brought into consciousness their intrinsic energy is liberated.

In this way the instincts become integrated and ordered. When only the instinctual element of the archetypal content is active there is chaos (massa confusa).

Archetypes can change whilst the individual remains quite unconscious of their movements.

Conceivable they change spontaneously. The archetypal content of dreams disappears and is replaced by a new one, even when the earlier form has not come into consciousness.

From the nature of a particular archetype it is possible to predict which will follow it.

It can be assumed that the flow of archetypes at a particular time characterize that historical period in a particular way.

The typical events of an era are determined by the succession and the quality of the corresponding archetypal images. The succession of the archetypal motives is a collective development and has nothing to do with the individual. We may imagine that the archetypes, being only the residual deposits of human experiences, would have represented animalistic life in an earlier period.

The archetypal primordial forms were already present, however, at the dawn of human consciousness; at its centre, everything was already there as an apriori possibility.

Even the first experiences of man were already fixed; we can only translate these patterns, these archetypes, into form we can understand.

Men have to realize the archetypes which are present at an unconscious level in creation.

All potentialities lie in the unconscious like ideas that have not yet been embodied nor experienced yet as reality.

The archetypes are present in the unconscious as potential abilities which, at a given moment, are realized and applied when brought into consciousness by a creative act.

As an analogy we can suppose that every inspiration produced out of the unconscious has a history.

A new situation occurs as a constellation produced by the archetype, a new inspiration emerges, and something else is discovered and becomes a part of reality.

A host of possibilities is still embedded in the archetypes, in the realm of the Mothers.

The abundance of possibilities eludes our comprehension.

The origin of the archetypes is a crucial question.

Where space and time are relative it is not possible to speak of developments in time.

Everything is present, altogether and all at once, in the constant presence of the pleroma.

I remember standing on a mountain top in inner Africa, seeing around me an endless expanse of brush and herds of animals grazing, all in a deep silence as it had been for thousands of years without anyone being aware of it. "They" were present but not consciously seen; they were as nameless as in Paradise before Adam named them.

Name-giving is an act of creation.

Where space and time do not exist there is only oneness (monotes).

There is no differentiation; there is only pleroma.

Pleroma is always with us, under our feet and above our heads.

Man is the point that has become visible, stepping out from the pleroma, knowing what he is doing, and able to name the things about him. Although the earth existed before there were any human beings, it could not be seen or known by anyone.

In China they say that the ancestor of the family, the one who stood at the beginning, is the Cosmos. Out of him was everything created: in the time before time.

There is nothing to explain or distinguish in the oneness because sequence and causality do not exist. The archetypes are the material of the God- Creator. The constitute a primeval ocean charged with potentiality. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Pages 21-22.

…a creative process, so far as we are able to follow it at all, consists in the unconscious activation of an archetypal image, and in elaborating and shaping this image into the finished work by giving it shape, the artist translates it into the language of the present and so makes it possible for us to find our way back to the deepest springs of life.

Therein lies the social significance of art: it is constantly at work educating the spirit of age, conjuring up the forms in which the age is most lacking ~Carl Jung, CW 15, Page 82.

"The "archetype" is practically synonymous with the biological concept of the behaviour pattern. But as the latter designates external phenomena chiefly, I have chosen the term "archetype" for "psychic pattern." ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 151-154.

Often when people behave in an exceedingly unexpected manner the appearance of an archetype is the explanation ; archetypes go back not only through human history, but to our ancestors the animals, that is why we are able to understand animals so well and make friends with them. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lectures, Vol. 2, Page 177.

The moment where the archetype appears is always characterized by remarkable emotion; it, as it were, fascinates the dreamer and exalts him, as if the Muse had kissed him not only on the forehead but on the shoulder. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 177.

It is when we come to a summit in life that the archetypal symbols appear. These primeval pictures of human life form the collective unconscious. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Pages 176-177.

It is also a plausible hypothesis that the archetype is produced by the original life urge and then gradually grows up into consciousness-with the qualification, however, that the innermost essence of the archetype can never become wholly conscious, since it is beyond the power of imagination and language to grasp and express its deepest nature. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Page 313.

When all the archetypal images are properly placed in a hierarchy, when that which must be below is below, and that which must be above is above, our final condition can recapture our original blissful state.

Archetypes are images in the soul that represent the course of one's life.

One part of the archetypal content is of material and the other of spiritual origin.

The more an archetype is amplified the more understandable it becomes.

It is hard to explain because the spiritual cannot be expressed in a few words.

The archetype signifies that particular spiritual reality which cannot be attained unless life is lived in consciousness.

Archetypes are not matters of faith; we can know that they are there.

An archetype is composed of an instinctual factor and a spiritual image.

The approaches to it from the instinctual or the spiritual side are very different.

The libido cannot be freed, however, unless the archetypal images can be made conscious.

When fantasy pictures are brought into consciousness their intrinsic energy is liberated.

In this way the instincts become integrated and ordered. When only the instinctual element of the archetypal content is active there is chaos (massa confusa).

Archetypes can change whilst the individual remains quite unconscious of their movements.

Conceivable they change spontaneously. The archetypal content of dreams disappears and is replaced by a new one, even when the earlier form has not come into consciousness.

From the nature of a particular archetype it is possible to predict which will follow it.

It can be assumed that the flow of archetypes at a particular time characterize that historical period in a particular way.

The typical events of an era are determined by the succession and the quality of the corresponding archetypal images. The succession of the archetypal motives is a collective development and has nothing to do with the individual. We may imagine that the archetypes, being only the residual deposits of human experiences, would have represented animalistic life in an earlier period.

The archetypal primordial forms were already present, however, at the dawn of human consciousness; at its centre, everything was already there as an apriori possibility.

Even the first experiences of man were already fixed; we can only translate these patterns, these archetypes, into form we can understand.

Men have to realize the archetypes which are present at an unconscious level in creation.

All potentialities lie in the unconscious like ideas that have not yet been embodied nor experienced yet as reality.

The archetypes are present in the unconscious as potential abilities which, at a given moment, are realized and applied when brought into consciousness by a creative act.

As an analogy we can suppose that every inspiration produced out of the unconscious has a history.

A new situation occurs as a constellation produced by the archetype, a new inspiration emerges, and something else is discovered and becomes a part of reality.

A host of possibilities is still embedded in the archetypes, in the realm of the Mothers.

The abundance of possibilities eludes our comprehension.

The origin of the archetypes is a crucial question.

Where space and time are relative it is not possible to speak of developments in time.

Everything is present, altogether and all at once, in the constant presence of the pleroma.

I remember standing on a mountain top in inner Africa, seeing around me an endless expanse of brush and herds of animals grazing, all in a deep silence as it had been for thousands of years without anyone being aware of it. "They" were present but not consciously seen; they were as nameless as in Paradise before Adam named them.

Name-giving is an act of creation.

Where space and time do not exist there is only oneness (monotes).

There is no differentiation; there is only pleroma.

Pleroma is always with us, under our feet and above our heads.

Man is the point that has become visible, stepping out from the pleroma, knowing what he is doing, and able to name the things about him. Although the earth existed before there were any human beings, it could not be seen or known by anyone.

In China they say that the ancestor of the family, the one who stood at the beginning, is the Cosmos. Out of him was everything created: in the time before time.

There is nothing to explain or distinguish in the oneness because sequence and causality do not exist. The archetypes are the material of the God- Creator. The constitute a primeval ocean charged with potentiality. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Pages 21-22.

…a creative process, so far as we are able to follow it at all, consists in the unconscious activation of an archetypal image, and in elaborating and shaping this image into the finished work by giving it shape, the artist translates it into the language of the present and so makes it possible for us to find our way back to the deepest springs of life.

Therein lies the social significance of art: it is constantly at work educating the spirit of age, conjuring up the forms in which the age is most lacking ~Carl Jung, CW 15, Page 82.

"The "archetype" is practically synonymous with the biological concept of the behaviour pattern. But as the latter designates external phenomena chiefly, I have chosen the term "archetype" for "psychic pattern." ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 151-154.

Archetypal image:

The form or representation of an archetype in consciousness. [The archetype is] a dynamism which makes itself felt in the numinosity and fascinating power of the archetypal image.["On the Nature of the Psyche," CW 8, par. 414.]

Archetypal images, as universal patterns or motifs which come from the collective unconscious, are the basic content of religions, mythologies, legends and fairy tales.

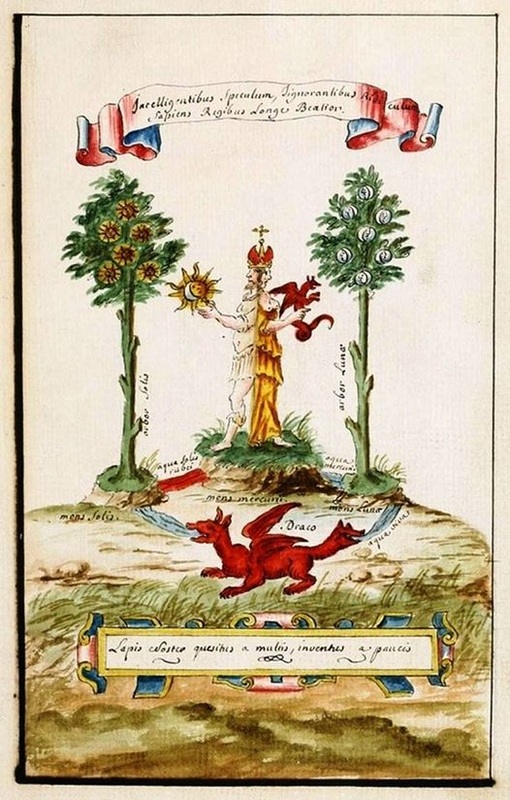

An archetypal content expresses itself, first and foremost, in metaphors. If such a content should speak of the sun and identify with it the lion, the king, the hoard of gold guarded by the dragon, or the power that makes for the life and health of man, it is neither the one thing nor the other, but the unknown third thing that finds more or less adequate expression in all these similes, yet-to the perpetual vexation of the intellect-remains unknown and not to be fitted into a formula.["The Psychology of the Child Archetype," CW 9i, par. 267]

On a personal level, archetypal motifs are patterns of thought or behavior that are common to humanity at all times and in all places. For years I have been observing and investigating the products of the unconscious in the widest sense of the word, namely dreams, fantasies, visions, and delusions of the insane.

I have not been able to avoid recognizing certain regularities, that is, types. There are types of situations and types of figures that repeat themselves frequently and have a corresponding meaning. I therefore employ the term "motif" to designate these repetitions. Thus there are not only typical dreams but typical motifs in dreams. . . .

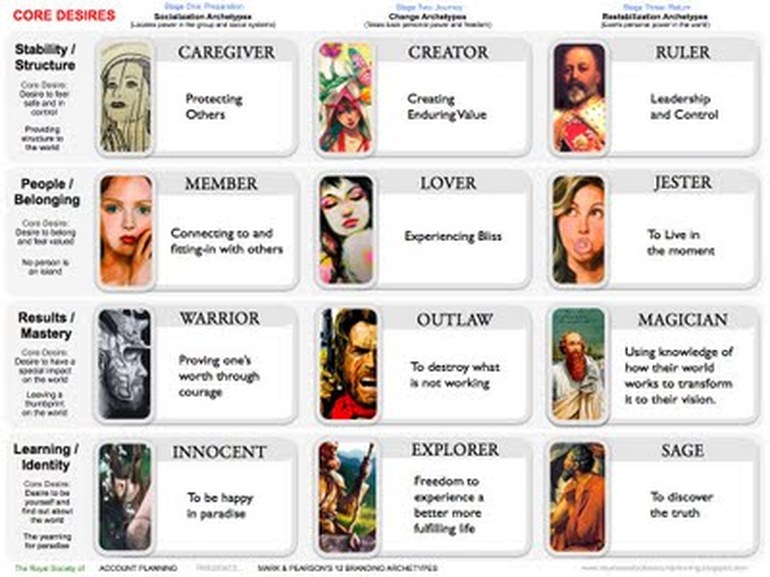

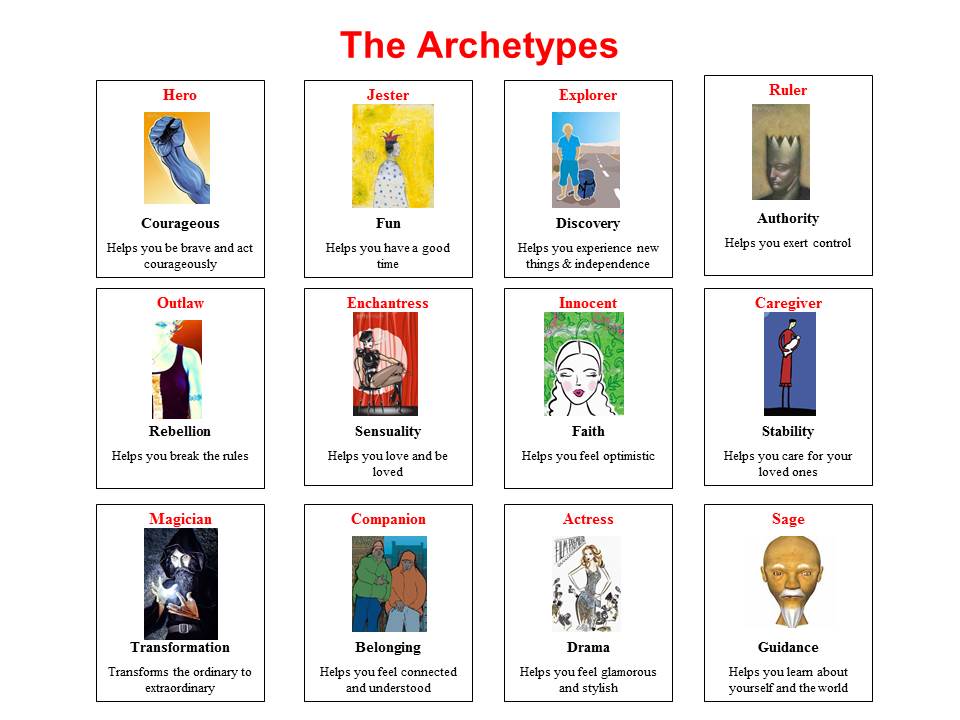

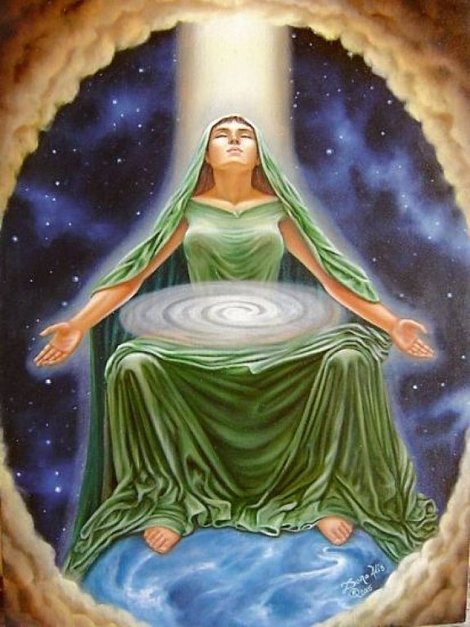

[These] can be arranged under a series of archetypes, the chief of them being . . . the shadow, the wise old man, the child (including the child hero), the mother ("Primordial Mother"and "Earth Mother") as a supraordinate personality ("daemonic"because supraordinate), and her counterpart the maiden, and lastly the anima in man and the animus in woman.["The Psychological Aspects of the Kore,"ibid., par. 309.]

The form or representation of an archetype in consciousness. [The archetype is] a dynamism which makes itself felt in the numinosity and fascinating power of the archetypal image.["On the Nature of the Psyche," CW 8, par. 414.]

Archetypal images, as universal patterns or motifs which come from the collective unconscious, are the basic content of religions, mythologies, legends and fairy tales.

An archetypal content expresses itself, first and foremost, in metaphors. If such a content should speak of the sun and identify with it the lion, the king, the hoard of gold guarded by the dragon, or the power that makes for the life and health of man, it is neither the one thing nor the other, but the unknown third thing that finds more or less adequate expression in all these similes, yet-to the perpetual vexation of the intellect-remains unknown and not to be fitted into a formula.["The Psychology of the Child Archetype," CW 9i, par. 267]

On a personal level, archetypal motifs are patterns of thought or behavior that are common to humanity at all times and in all places. For years I have been observing and investigating the products of the unconscious in the widest sense of the word, namely dreams, fantasies, visions, and delusions of the insane.

I have not been able to avoid recognizing certain regularities, that is, types. There are types of situations and types of figures that repeat themselves frequently and have a corresponding meaning. I therefore employ the term "motif" to designate these repetitions. Thus there are not only typical dreams but typical motifs in dreams. . . .

[These] can be arranged under a series of archetypes, the chief of them being . . . the shadow, the wise old man, the child (including the child hero), the mother ("Primordial Mother"and "Earth Mother") as a supraordinate personality ("daemonic"because supraordinate), and her counterpart the maiden, and lastly the anima in man and the animus in woman.["The Psychological Aspects of the Kore,"ibid., par. 309.]

If so, the position of the archetype would be located beyond the psychic sphere, analogous to the position of physiological instinct, which is immediately rooted in the stuff of the organism and, with its psychoid nature, forms the bridge to matter in general. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Para 420.

Since psyche and matter are contained in one and the same world, and moreover are in continuous contact with one another and ultimately rest on irrepresentable, transcendental factors, it is not only

possible but fairly probable, even, that psyche and matter are two different aspects of one and the same thing.

The synchronicity phenomena point, it seems to me, in this direction, for they show that the nonpsychic can behave like the psychic, and vice versa, without there being any causal connection between

them.

Our present knowledge does not allow us to do much more than compare the relation of the psychic to the material world with two cones, whose apices, meeting in a point without extension—a real

zero-point—touch and do not touch.

In my previous writings I have always treated archetypal phenomena as psychic, because the material to be expounded or investigated was concerned solely with ideas and images.

The psychoid nature of the archetype, as put forward here, does not contradict these earlier formulations; it only means a further degree of conceptual differentiation, which became inevitable as soon as I saw myself obliged to undertake a more general analysis of the nature of the psyche and to clarify the empirical concepts concerning it, and their relation to one another.

Just as the "psychic infra-red," the biological instinctual psyche, gradually passes over into the physiology of the organism and thus merges with its chemical and physical conditions, so the "psychic ultra-violet,"

the archetype, describes a field which exhibits none of the peculiarities of the physiological and yet, in the last analysis, can no longer be regarded as psychic, although it manifests itself psychically.

But physiological processes behave in the same way, without on that account being declared psychic.

Although there is no form of existence that is not mediated to us psychically and only psychically, it would hardly do to say that everything is merely psychic.

We must apply this argument logically to the archetypes as well.

Since their essential being is unconscious to us, and still they are experienced as spontaneous agencies, there is probably no alternative now but to describe their nature, in accordance with their

chiefest effect, as "spirit," in the sense which I attempted to make plain in my paper "The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales."

If so, the position of the archetype would be located beyond the psychic sphere, analogous to the position of physiological instinct, which is immediately rooted in the stuff of the organism and, with its

psychoid nature, forms the bridge to matter in general.

In archetypal conceptions and instinctual perceptions, spirit and matter confront one another on the psychic plane.

Matter and spirit both appear in the psychic realm as distinctive qualities of conscious contents.

The ultimate nature of both is transcendental, that is, irrepresentable, since the psyche and its contents are the only reality which is given to us without a medium.

~Carl Jung, CW 8, Pages 215-216.

Since psyche and matter are contained in one and the same world, and moreover are in continuous contact with one another and ultimately rest on irrepresentable, transcendental factors, it is not only

possible but fairly probable, even, that psyche and matter are two different aspects of one and the same thing.

The synchronicity phenomena point, it seems to me, in this direction, for they show that the nonpsychic can behave like the psychic, and vice versa, without there being any causal connection between

them.

Our present knowledge does not allow us to do much more than compare the relation of the psychic to the material world with two cones, whose apices, meeting in a point without extension—a real

zero-point—touch and do not touch.

In my previous writings I have always treated archetypal phenomena as psychic, because the material to be expounded or investigated was concerned solely with ideas and images.

The psychoid nature of the archetype, as put forward here, does not contradict these earlier formulations; it only means a further degree of conceptual differentiation, which became inevitable as soon as I saw myself obliged to undertake a more general analysis of the nature of the psyche and to clarify the empirical concepts concerning it, and their relation to one another.

Just as the "psychic infra-red," the biological instinctual psyche, gradually passes over into the physiology of the organism and thus merges with its chemical and physical conditions, so the "psychic ultra-violet,"

the archetype, describes a field which exhibits none of the peculiarities of the physiological and yet, in the last analysis, can no longer be regarded as psychic, although it manifests itself psychically.

But physiological processes behave in the same way, without on that account being declared psychic.

Although there is no form of existence that is not mediated to us psychically and only psychically, it would hardly do to say that everything is merely psychic.

We must apply this argument logically to the archetypes as well.

Since their essential being is unconscious to us, and still they are experienced as spontaneous agencies, there is probably no alternative now but to describe their nature, in accordance with their

chiefest effect, as "spirit," in the sense which I attempted to make plain in my paper "The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales."

If so, the position of the archetype would be located beyond the psychic sphere, analogous to the position of physiological instinct, which is immediately rooted in the stuff of the organism and, with its

psychoid nature, forms the bridge to matter in general.

In archetypal conceptions and instinctual perceptions, spirit and matter confront one another on the psychic plane.

Matter and spirit both appear in the psychic realm as distinctive qualities of conscious contents.

The ultimate nature of both is transcendental, that is, irrepresentable, since the psyche and its contents are the only reality which is given to us without a medium.

~Carl Jung, CW 8, Pages 215-216.

Mythos and Logos, Shelburne

Complex/Archetype/Symbol In The Psychology Of C G Jung By Jacobi, Jolande, pg 34

The archetypes are outside as well as inside ourselves. They are dynamic processes and self-organizing patterns as well as static representations.

In talking about archetypes, it helps to note that Jung's experience with archetypes was that they are dynamic patterns, fields of potential, which have both forceful intentionality and complete independence. They are raw nature at the heart of the psyche, and, as such, serve as the foundational material for our complexes, both “good” and “bad.” The central archetype, the Self, is the transpersonal center of the psyche, and acts as the instrument and agent of transcendence. As such, it is indistinguishable from the God-image.

Our Ancestors Calling

We are THE WATCHERS; They are THE WATCHERS

Archetypes are complexes of experience that come upon us like fate, and their effects are felt in our most personal life. The anima no longer crosses our path as a goddess, but, it may be, as an intimately personal misadventure, or perhaps as our best venture. When, for instance, a highly esteemed professor in his seventies abandons his family and runs off with a young red-headed actress, we know that the gods have claimed another victim. ~Carl Jung; "Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious"; CW 9, Part I: The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Page 62.

Our psyche can function as though space did not exist. The psyche can thus be independent of space, of time, and of causality. This explains the possibility of magic. ~C. G. Jung, Emma Jung and Toni Wolff - A Collection of Remembrances; Pages 51-70.

The archetypes are, so to speak, organs of the pre-rational psyche.

They are eternally inherited forms and ideas which have at first no specific content. Their specific content only appears in the course of the individual's life, when personal experience is taken up in precisely these forms. ~Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion, Page 518.

Your conception of the archetype as a psychic gene is quite possible.

It is also a plausible hypothesis that the archetype is produced by the original life urge and then gradually grows up into consciousness-with the qualification, however, that the innermost essence of the archetype can never become wholly conscious, since it is beyond the power of imagination and language to grasp and express its deepest nature.

It can only be experienced as an image.

Hence the archetype can never enter consciousness in its entirety but remains a borderline phenomenon, in the sense that external stimuli impinge upon the inner archetypal datum in a zone of friction, which is precisely what we might describe consciousness as being.

This view would do greater justice to the essentially conflicting nature of consciousness.

Yours sincerely,

C.G. Jung

"On the Nature' of the Psyche," CW 8, pars. 41 7f.

In talking about archetypes, it helps to note that Jung's experience with archetypes was that they are dynamic patterns, fields of potential, which have both forceful intentionality and complete independence. They are raw nature at the heart of the psyche, and, as such, serve as the foundational material for our complexes, both “good” and “bad.” The central archetype, the Self, is the transpersonal center of the psyche, and acts as the instrument and agent of transcendence. As such, it is indistinguishable from the God-image.

Our Ancestors Calling

We are THE WATCHERS; They are THE WATCHERS

Archetypes are complexes of experience that come upon us like fate, and their effects are felt in our most personal life. The anima no longer crosses our path as a goddess, but, it may be, as an intimately personal misadventure, or perhaps as our best venture. When, for instance, a highly esteemed professor in his seventies abandons his family and runs off with a young red-headed actress, we know that the gods have claimed another victim. ~Carl Jung; "Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious"; CW 9, Part I: The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Page 62.

Our psyche can function as though space did not exist. The psyche can thus be independent of space, of time, and of causality. This explains the possibility of magic. ~C. G. Jung, Emma Jung and Toni Wolff - A Collection of Remembrances; Pages 51-70.

The archetypes are, so to speak, organs of the pre-rational psyche.

They are eternally inherited forms and ideas which have at first no specific content. Their specific content only appears in the course of the individual's life, when personal experience is taken up in precisely these forms. ~Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion, Page 518.

Your conception of the archetype as a psychic gene is quite possible.

It is also a plausible hypothesis that the archetype is produced by the original life urge and then gradually grows up into consciousness-with the qualification, however, that the innermost essence of the archetype can never become wholly conscious, since it is beyond the power of imagination and language to grasp and express its deepest nature.

It can only be experienced as an image.

Hence the archetype can never enter consciousness in its entirety but remains a borderline phenomenon, in the sense that external stimuli impinge upon the inner archetypal datum in a zone of friction, which is precisely what we might describe consciousness as being.

This view would do greater justice to the essentially conflicting nature of consciousness.

Yours sincerely,

C.G. Jung

"On the Nature' of the Psyche," CW 8, pars. 41 7f.

"When all the archetypal images are properly placed in a hierarchy, when that which must be below is below, and that which must be above is above, our final condition can recapture our original blissful state.

Archetypes are images in the soul that represent the course of one's life. One part of the archetypal content is of material and the other of spiritual origin.

The more an archetype is amplified the more understandable it becomes.

It is hard to explain because the spiritual cannot be expressed in a few words.

The archetype signifies that particular spiritual reality which cannot be attained unless life is lived in consciousness. Archetypes are not matters of faith; we can know that they are there.

An archetype is composed of an instinctual factor and a spiritual image. The approaches to it from the instinctual or the spiritual side are very different.

The libido cannot be freed, however, unless the archetypal images can be made conscious.

When fantasy pictures are brought into consciousness their intrinsic energy is liberated.

In this way the instincts become integrated and ordered.

When only the instinctual element of the archetypal content is active there is chaos (massa confusa).

Archetypes can change whilst the individual remains quite unconscious of their movements.

Conceivable they change spontaneously. The archetypal content of dreams disappears and is replaced by a new one, even when the earlier form has not come into consciousness.

From the nature of a particular archetype it is possible to predict which will follow it.

It can be assumed that the flow of archetypes at a particular time characterize that historical period in a particular way.

The typical events of an era are determined by the succession and the quality of the corresponding archetypal images.

The succession of the archetypal motives is a collective development and has nothing to do with the individual.

We may imagine that the archetypes, being only the residual deposits of human experiences, would have represented animalistic life in an earlier period.

The archetypal primordial forms were already present, however, at the dawn of human consciousness; at its centre, everything was already there as an apriori possibility.

Even the first experiences of man were already fixed; we can only translate these patterns, these archetypes, into form we can understand.

Men have to realize the archetypes which are present at an unconscious level in creation.

All potentialities lie in the unconscious like ideas that have not yet been embodied nor experienced yet as reality.

The archetypes are present in the unconscious as potential abilities which, at a given moment, are realized and applied when brought into consciousness by a creative act.

As an analogy we can suppose that every inspiration produced out of the unconscious has a history.

A new situation occurs as a constellation produced by the archetype, a new inspiration emerges, and something else is discovered and becomes a part of reality.

A host of possibilities is still embedded in the archetypes, in the realm of the Mothers.

The abundance of possibilities eludes our comprehension.

The origin of the archetypes is a crucial question. Where space and time are relative it is not possible to speak of developments in time.

Everything is present, altogether and all at once, in the constant presence of the pleroma.

I remember standing on a mountain top in Kenya Africa, seeing around me an endless expanse of brush and herds of animals grazing, all in a deep silence as it had been for thousands of years without anyone being aware of it.

"They" were present but not consciously seen; they were as nameless as in Paradise before Adam named them.

Name-giving is an act of creation.

Where space and time do not exist there is only oneness (monofes). There is no differentiation; there is only pleroma.

Pleroma is always with us, under our feet and above our heads.

Man is the point that has become visible, stepping out from the pleroma, knowing what he is doing, and able to name the things about him.

Although the earth existed before there were any human beings, it could not be seen or known by anyone.

In China they say that the ancestor of the family, the one who stood at the beginning, is the Cosmos. Out of him was everything created in the time before time. There is nothing to explain or distinguish in the oneness because sequence and causality do not exist.

The archetypes are the material of the God- Creator. They constitute a primeval ocean charged with potentiality. ~Carl Jung; Conversations with C.G. Jung, Archetypes, Pages 21-22.

"If you follow Jung, each archetype, creating a pattern of behavior and a model image, informs the conscience and consciousness has its own style ... because consciousness refers to a process that has more to do with the images that with the will, most with the reflection than the ordering activity, with the thoughtful look which penetrates into the "objective reality" rather than by manipulating the same. " --James Hillman

I have often been asked where the archetype comes from and whether it is acquired or not. This question cannot be answered directly.

Archetypes are, by definition, factors and motifs that arrange the psychic elements into certain images, characterized as archetypal, but in such a way that they can be recognized only from the effects they produce.

They exist preconsciously, and presumably they form the structural dominants of the psyche in general.

They may be compared to the invisible presence of the crystal lattice in a saturated solution.

As a priori conditioning factors they represent a special, psychological instance of the biological "pattern of behavior," which gives all living organisms their specific qualities. Just as the manifestations of this biological ground plan may change in the course of development, so also can those of the archetype.

Empirically considered, however, the archetype did not ever come into existence as a phenomenon of organic life, but entered into the picture with life itself. ~"A Psychological Approach to the Dogma of the Trinity" (1942). In CW 11: Psychology and Religion: West and East. P. 222

Just as the "psychic infra-red," the biological instinctual psyche, gradually passes over into the physiology of the organism and thus merges with its chemical and physical conditions, so the "psychic ultra-violet," the archetype, describes a field which exhibits none of the peculiarities of the physiological and yet, in the last analysis, can no longer be regarded as psychic. ~Carl Jung; On the Nature of the Psyche; CW 8: The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche; Page 420.

The Unconscious: Archetypes

Evans: You mentioned earlier that Freud's Oedipal situation was an example of an archetype. At this time would you please elaborate on the concept, archetype?

Jung: Well, you know what a behavior pattern is, the way in which a weaver bird builds its nest. That is an inherited form in him. He will apply certain symbiotic phenomena, between insects and plants. They are inherited patterns of behavior. And so man has, of course, an inherited scheme of functioning. You see, his liver, his heart, all his organs, and his brain will always function in a certain way, following its pattern. You may have a great difficulty seeing it because you cannot compare it. There are no other similar beings like man, that are articulate, that could give an account of their functioning. If that were the case, we could—I don't know what. But because we have no means of comparison, we are necessarily unconscious about the whole conditions.

It is quite certain, however, that man is born with a certain functioning, a certain way of functioning, a certain pattern of behavior which is expressed in the form of archetypal images, or archetypal forms. For instance, the way in which a man should behave is expressed by an archetype. Therefore, you see, the primitives tell such stories. A great deal of education goes through story- telling. For instance, they call together the young men, and two older men act out before the eyes of the younger all the things they should not do. Then they say, "Now that's exactly the thing you shall not do.” Another way is they tell them all of the things they should not do, like the Decalogue, "Thou shalt not," and that is always supported by mythological tales.

That, of course, gave me a motive to study the archetypes, because I began to see that the structure of what I then called the collective unconscious was really a sort of agglomeration of such typical images, each of which had a unique quality.

The archetypes are, at the same time, dynamic. They are instinctual images that are not intellectually invented. They are always there and they produce certain processes in the unconscious that one could best compare with myths. That's the origin of mythology. Mythology is a pronouncing of a series of images that formulate the life of archetypes.

So the statements of every religion, of many poets, etc., are statements about the inner mythological process, which is a necessity because man is not complete if he is not conscious of that aspect of things. For instance, our ancestors have done so and so, and so shall you do. Or such and such a hero has done so and so, and that is your model. For instance, in the teachings of the Catholic church, there are several thousand saints. They show us how to do— They have their legends— And that is Christian mythology.

In Greece, you know, there was Theseus and there was Heracles, models of fine men, of gentlemen, you know; and they teach us how to behave. They are archetypes of behavior. I became more and more respectful of archetypes, and that naturally led me on to a profound study of them. And now, by Jove, there is an enormous factor, very important for our further development and for our well-being, that should be taken into account.

It was, of course, difficult to know where to begin, because it is such an enormously extended field. And the next question I asked myself was, "Now, where in the world has anybody been busy with that problem?" I found that nobody had except a peculiar spiritual movement that went together with the beginning of Christianity, namely, the Gnostics; and that was the first thing actually that I saw. They were concerned with the problem of archetypes, and made a peculiar philosophy of it. Everybody makes a peculiar philosophy of it when he comes across it naively, and doesn't know that those are structural elements of the unconscious psyche. The Gnostics lived in the first, second and third centuries; and I wanted to know what was in between that time and today, when we suddenly are confronted by the problems of the collective unconscious which were the same two thousand years ago, though we are not prepared to admit that problem. I was always looking for something in between, you know, something that would link that remote past with the present moment.

I found to my amazement that it was alchemy, that which is understood to be a history of chemistry. It was, one could almost say, nothing less than that. It was a peculiar spiritual movement or a philosophical movement. They called themselves philosophers, like Narcissism.

And then I read the whole accessible literature, Latin and Greek. I studied it because it was enormously interesting. It is the mental work of 1,700 years, in which there is stored up all they could make out about the nature of the archetypes, in a peculiar way that's foolish. It is not simple. Most of the texts are no more published since the middle ages, the last editions dated in the middle or the end of the sixteenth century, all in Latin; some texts are in Greek, not a few very important ones. That has given me no end of work, but the result was most satisfactory, because it showed me the development of our unconscious relation to the collective unconscious and the variations our consciousness has undergone; why the being's unconscious is concerned with these mythological images.

For instance, such phenomena as in Hitler, you know. That is a psychical phenomenon, and we've got to understand these things. To me, of course, it has been an enormous problem because it is a factor that has determined the fate of millions of European people, and of Americans. Nobody can deny that he has been influenced by the war. That was all Hitler's doing—and that's all psychology, our foolish psychology. But you only come to an understanding of these things when you understand the background from which it springs. It is just as though, as if a terrific epidemic of typhoid fever were breaking out, and you say, "That is typhoid fever— isn't that a marvelous disease!" It can take on enormous dimensions and nobody knows anything about it. Nobody takes care of the water supply, nobody thinks of examining the meat or anything like that; but everyone simply states, "This is a phenomenon.” —Yes, but one doesn't understand it.

Of course, I cannot tell you in detail about alchemy. It is the basic of our modern way of conceiving things, and therefore, it is as if it were right under the threshold of consciousness. This is a wonderful picture of how the development of archetypes, the movement of archetypes, looks when you look upon them with broader perspective. Maybe from today you look back into the past and you see how the present moment has evolved out of the past. It is just as if the alchemistic philosophy— That sounds very curious; we should give it an entirely different name. Actually, it has a different name. It is also called Hermetic Philosophy, though, of course, that conveys just as little as the term alchemy. —It was the parallel development, as Narcissism was, to the conscious development of Christianity, of our Christian philosophy, of the whole psychology of the middle ages.

So you see, in our days we have such and such a view of the world, a particular philosophy, but in the unconscious we have a different one. That we can see through the example of the alchemistic philosophy that behaves to the medieval consciousness exactly like the unconscious behaves to ourselves. And we can construct or even predict the unconscious of our days when we know what it has been yesterday.

Or, for instance, to take a more concise archetype, like the archetype of the ford—the ford to a river. Now that is a whole situation. You have to cross a ford; you are in the water; and there is an ambush or a water animal, say a crocodile or something like that. There is danger and something is going to happen. The problem is how you escape. Now this is a whole situation and it makes an archetype. And that archetype has now a suggestive effect upon you. For instance, you get into a situation; you don't know what the situation is; you suddenly are seized by an emotion or by a spell; and you behave in a certain way you have not foreseen at all—you do something quite strange to yourself.

Evans: Could this also be described as spontaneous?

Jung: Quite spontaneous. And that is done through the archetype that is concerned. Of course, we have a famous case in our Swiss history of the King Albrecht, who was murdered in the ford of the Royce not very far from Zurich. His murderers were hiding behind him for the whole stretch from Zurich to the Royce, quite a long stretch, and after deliberating, still couldn't come together about whether they wanted to kill the king or not. The moment the king rode into the ford, they thought, "Murder!" They shouted, "Why do we let him abuse us?" Then they killed him, because this was the moment they were seized; this was the right moment. So you see, when you have lived in primitive circumstances, in the primeval forest among primitive populations, then you know that phenomenon. You are seized with a certain spell and you do a thing that is unexpected.

Several times when I was in Africa, I went into such situations where I was amazed afterwards. One day I was in the Sudan and it was really a very dangerous situation, which I didn't recognize at the moment at all. But I was seized with a spell. I did something which I wouldn't have expected and I couldn't have intended.