Dreams

Ancestral Dreams

by Iona Miller, (c)2015

As far as my knowledge goes we are aware in dreams of our other life that consists in the first place of all the things we have not yet lived or experienced in the flesh. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 341

We also live in our dreams, we do not live only by day.

Sometimes we accomplish our greatest deeds in dreams.

~Carl Jung; The Red Book. Page 242.

As far as my knowledge goes we are aware in dreams of our other life that consists in the first place of all the things we have not yet lived or experienced in the flesh. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 341

Sometimes we accomplish our greatest deeds in dreams.

~Carl Jung; The Red Book. Page 242.

As far as my knowledge goes we are aware in dreams of our other life that consists in the first place of all the things we have not yet lived or experienced in the flesh. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 341

“In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.” ―Aeschylus

As most people know, one of the basic principles of analytical psychology is that dream-images are to be understood symbolically; that is to say, one must not take them literally, but must surmise a hidden meaning in them. ~Jung; Symbols of Transformation; para 4.

Everything psychic has a lower and a higher meaning, as in the profound saying of late classical mysticism: ‘Heaven above, Heaven below, stars above, stars below, all that is above also is below, know this and rejoice.’ Here we lay our finger on the secret symbolical significance of everything psychic. ~Carl Jung; CW 5; para 77.

The question may be formulated simply as follows: ‘What is the purpose of this dream? What effect is it meant to have? These questions are not arbitrary inasmuch as they can be applied to every psychic activity. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, para. 462.

The wise old man appears in dreams in the guise of a magician, doctor, priest, teacher, professor, grandfather, or any person possessing authority. ~Carl Jung, CW 9i, Par. 398.

The feminine equivalent in both men and women is the Great Mother. The figure of the wise old man can appear so plastically, not only in dreams but also in visionary meditation (or what we call "active imagination"), that . . . it takes over the role of a guru. ~Carl Jung, CW 9i, Par. 398.

There is no difference in principle between organic and psychic growth. As a plant produces its flower, so the psyche creates its symbols. Every dream is evidence of this process. ~Carl Jung, Man and His Symbols, Page 64.

I have observed the case of a man who had no dreams, but his nine-year-old son had all his father's dreams which I could analyse for the benefit of the father. ~Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 62-64.

I don't use free association at all since it is in any case an unreliable method of getting at the real dream material. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 292-294.

That is to say, by means of "free" association you will always get at your complexes, but this does not mean at all that they are the material dreamt about. ~ Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pg. 292-294.

As most people know, one of the basic principles of analytical psychology is that dream-images are to be understood symbolically; that is to say, one must not take them literally, but must surmise a hidden meaning in them. ~Jung; Symbols of Transformation; para 4.

Everything psychic has a lower and a higher meaning, as in the profound saying of late classical mysticism: ‘Heaven above, Heaven below, stars above, stars below, all that is above also is below, know this and rejoice.’ Here we lay our finger on the secret symbolical significance of everything psychic. ~Carl Jung; CW 5; para 77.

The question may be formulated simply as follows: ‘What is the purpose of this dream? What effect is it meant to have? These questions are not arbitrary inasmuch as they can be applied to every psychic activity. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, para. 462.

The wise old man appears in dreams in the guise of a magician, doctor, priest, teacher, professor, grandfather, or any person possessing authority. ~Carl Jung, CW 9i, Par. 398.

The feminine equivalent in both men and women is the Great Mother. The figure of the wise old man can appear so plastically, not only in dreams but also in visionary meditation (or what we call "active imagination"), that . . . it takes over the role of a guru. ~Carl Jung, CW 9i, Par. 398.

There is no difference in principle between organic and psychic growth. As a plant produces its flower, so the psyche creates its symbols. Every dream is evidence of this process. ~Carl Jung, Man and His Symbols, Page 64.

I have observed the case of a man who had no dreams, but his nine-year-old son had all his father's dreams which I could analyse for the benefit of the father. ~Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 62-64.

I don't use free association at all since it is in any case an unreliable method of getting at the real dream material. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 292-294.

That is to say, by means of "free" association you will always get at your complexes, but this does not mean at all that they are the material dreamt about. ~ Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pg. 292-294.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Dante´s Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice

Dreams, the realm of the collective unconscious, are where our holographic and ancestral memories live, and we can access them from there, and they likewise access us through the dreamworld.

Carl Jung brought the topic of mythology into psychotherapy, and he wrote about his own "personal myth." One approach to dreamwork is the identification of the functional or dysfunctional personal myth (or belief system) embedded in the dream. This personal myth usually is implicit or explicit in what Hartmann calls the "central image" of the dream. In addition, it typically serves as the "chaotic attractor" that self-organizes material drawn to it by the sleeping brain's neural networks. Jung's perspective on dreams is remarkably congruent with many findings in neuroscience as well as the self-regulatory processes that typify contemporary dream theory and research.

My collaborators and I have been studying what Jung called "big dreams" for some time. For various research studies we defined "big dreams" either as "memorable" dreams, as "important" dreams, as "especially significant" dreams, and as "impactful" dreams. In each case we found that the "big dreams" were characterized by significantly higher Central Image Intensity than control groups of dreams - thus more powerful imagery. We did not find clear differences in Content Analysis scoring of these dreams. We will discuss these studies and also present a possible neurobiology of "big dreams."

In an early work, Jung wrote about two types of thinking, directed and fantasy thinking, He had in mind what we might today see as the difference between left brain analytical thinking with words and right brain thinking in images and stories. The brain works differently in each mode, with different areas active and with different chemicals suffusing the neurons. Jung's two types combine what we would now distinguish as right and left brain activity while awake and dream thinking while we are asleep. In referring to the lunar mind, I am speaking about the sleeping mind at work as it dreams us and also the (probably mostly) right brain activity that we use in active imagination. In Jungian psychoanalysis, we are concerned with bringing lunar and solar minds into contact with one another in the field of an analytic relationship, and working with dreams is an essential aspect of this process.

Insights from contemporary neurobiology support rather than contest Jung's view that emotional truth underpins the dreaming process. Recent imaging studies confirm that dreams are the mind's vehicle for the processing of emotional states of being, particularly the fear, anxiety, anger or elation that often figure prominently. Dream sleep is also the guardian of memory, playing a part in forgetting, encoding and affective organization of memory.In the clinical sections of the presentation Margaret will let the dreams speak, revealing the emotionally salient concerns of the dreamers in a way that demonstrates the healthy attempt of the brain-mind to come to terms with difficult emotional experience. The dreams become dreamable as part of the meaning-making process.

Dreams...are invariably seeking to express something that the ego does not know and does not understand. ~Carl Jung Quotation, CW 17, Paragraph 187

Carl Jung brought the topic of mythology into psychotherapy, and he wrote about his own "personal myth." One approach to dreamwork is the identification of the functional or dysfunctional personal myth (or belief system) embedded in the dream. This personal myth usually is implicit or explicit in what Hartmann calls the "central image" of the dream. In addition, it typically serves as the "chaotic attractor" that self-organizes material drawn to it by the sleeping brain's neural networks. Jung's perspective on dreams is remarkably congruent with many findings in neuroscience as well as the self-regulatory processes that typify contemporary dream theory and research.

My collaborators and I have been studying what Jung called "big dreams" for some time. For various research studies we defined "big dreams" either as "memorable" dreams, as "important" dreams, as "especially significant" dreams, and as "impactful" dreams. In each case we found that the "big dreams" were characterized by significantly higher Central Image Intensity than control groups of dreams - thus more powerful imagery. We did not find clear differences in Content Analysis scoring of these dreams. We will discuss these studies and also present a possible neurobiology of "big dreams."

In an early work, Jung wrote about two types of thinking, directed and fantasy thinking, He had in mind what we might today see as the difference between left brain analytical thinking with words and right brain thinking in images and stories. The brain works differently in each mode, with different areas active and with different chemicals suffusing the neurons. Jung's two types combine what we would now distinguish as right and left brain activity while awake and dream thinking while we are asleep. In referring to the lunar mind, I am speaking about the sleeping mind at work as it dreams us and also the (probably mostly) right brain activity that we use in active imagination. In Jungian psychoanalysis, we are concerned with bringing lunar and solar minds into contact with one another in the field of an analytic relationship, and working with dreams is an essential aspect of this process.

Insights from contemporary neurobiology support rather than contest Jung's view that emotional truth underpins the dreaming process. Recent imaging studies confirm that dreams are the mind's vehicle for the processing of emotional states of being, particularly the fear, anxiety, anger or elation that often figure prominently. Dream sleep is also the guardian of memory, playing a part in forgetting, encoding and affective organization of memory.In the clinical sections of the presentation Margaret will let the dreams speak, revealing the emotionally salient concerns of the dreamers in a way that demonstrates the healthy attempt of the brain-mind to come to terms with difficult emotional experience. The dreams become dreamable as part of the meaning-making process.

Dreams...are invariably seeking to express something that the ego does not know and does not understand. ~Carl Jung Quotation, CW 17, Paragraph 187

Dreams are the guiding words of the soul. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 233

The spirit of the depths even taught me to consider my action and my decision as dependent on dreams. Dreams pave the way for life, and they determine you without you understanding their language. ~ Carl Jung, Red Book, Page 233.

I must learn that the dregs of my thought, my dreams, are the speech of my soul. I must carry them in my heart, and go back and forth over them in my mind, like the words of the person dearest to me. Dreams are the guiding words of the soul. ~Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 232.

Dreams may contain ineluctable truths, philosophical pronouncements, illusions, wild fantasies, memories, plans, anticipations, irrational experiences, even telepathic visions, and heaven knows what besides. ~Carl Jung, CW 16, Page 317

The spirit of the depths even taught me to consider my action and my decision as dependent on dreams. Dreams pave the way for life, and they determine you without you understanding their language. ~ Carl Jung, Red Book, Page 233.

I must learn that the dregs of my thought, my dreams, are the speech of my soul. I must carry them in my heart, and go back and forth over them in my mind, like the words of the person dearest to me. Dreams are the guiding words of the soul. ~Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 232.

Dreams may contain ineluctable truths, philosophical pronouncements, illusions, wild fantasies, memories, plans, anticipations, irrational experiences, even telepathic visions, and heaven knows what besides. ~Carl Jung, CW 16, Page 317

Our dreams propel us into a landscape of universal symbols, which

can speak both to our deepest personal realities and to the collective

archetypal world that underpins them.

~Claire Dunne, Wounded Healer of the Soul, Page 86.

We are so captivated by and entangled in our subjective consciousness that we have forgotten the age-old fact that God speaks chiefly through dreams and visions. ~Carl Jung, The Symbolic Life, Page 262.

In the last analysis, most of our difficulties come from losing contact with our instincts, with the age-old unforgotten wisdom stored up in us. And where do we make contact with this old man in us? In our dreams. ~Carl Jung, Psychological Reflections, 76.

They [Dreams] do not deceive, they do not lie, they do not distort or disguise… They are invariably seeking to express something that the ego does not know and does not understand. ~Carl Jung, CW 17, Para 189.

can speak both to our deepest personal realities and to the collective

archetypal world that underpins them.

~Claire Dunne, Wounded Healer of the Soul, Page 86.

We are so captivated by and entangled in our subjective consciousness that we have forgotten the age-old fact that God speaks chiefly through dreams and visions. ~Carl Jung, The Symbolic Life, Page 262.

In the last analysis, most of our difficulties come from losing contact with our instincts, with the age-old unforgotten wisdom stored up in us. And where do we make contact with this old man in us? In our dreams. ~Carl Jung, Psychological Reflections, 76.

They [Dreams] do not deceive, they do not lie, they do not distort or disguise… They are invariably seeking to express something that the ego does not know and does not understand. ~Carl Jung, CW 17, Para 189.

“When a man is in the wilderness, it is the darkness that brings the dreams.”

-Jung

The dream arises from a part of the mind unknown to us, but none the less important, and is concerned with the desires for the approaching day. --Carl Jung (The Psychology of the Unconscious, 1943)

Dreams as a whole are without purpose, like nature herself, it is wiser to regard them as such. --Jung, Lecture VII 8th March, 1935

We can have prophetic dreams without possessing second sight, innumerable people have such anticipatory dreams. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture V, Pages 26.

Who are you, child? My dreams have represented you as a child and as a maiden. I am ignorant of your mystery. Forgive me if I speak as in a dream, like a drunkard-are you God? Is God a child, a maiden? Forgive me if I babble. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 233.

You announced yourself to me in advance in dreams. They burned in my heart and drove me to all the boldest acts of daring, and forced me to rise above myself. You let me see truths of which I had no previous inkling. You let me undertake journeys, whose endless length would have scared me, if the knowledge of them had not been secure in you. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 233.

-Jung

The dream arises from a part of the mind unknown to us, but none the less important, and is concerned with the desires for the approaching day. --Carl Jung (The Psychology of the Unconscious, 1943)

Dreams as a whole are without purpose, like nature herself, it is wiser to regard them as such. --Jung, Lecture VII 8th March, 1935

We can have prophetic dreams without possessing second sight, innumerable people have such anticipatory dreams. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture V, Pages 26.

Who are you, child? My dreams have represented you as a child and as a maiden. I am ignorant of your mystery. Forgive me if I speak as in a dream, like a drunkard-are you God? Is God a child, a maiden? Forgive me if I babble. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 233.

You announced yourself to me in advance in dreams. They burned in my heart and drove me to all the boldest acts of daring, and forced me to rise above myself. You let me see truths of which I had no previous inkling. You let me undertake journeys, whose endless length would have scared me, if the knowledge of them had not been secure in you. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 233.

The third question asks if we can dream of experiences undergone by our ancestors. I cannot be sure of this. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 198.

The essential thing is not what the dreamer believes but what he is;

it is not my creed that matters, but what I am, every gesture betrays me.

~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 199.

There are certain dreams which seem really to concern themselves with the fate of the ego, but these belong to the category of big dreams. Dreams as a whole are without purpose, like nature herself, it is wiser to regard them as such.

~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 198.

All dreams originate in the unconscious though occasionally a dream can be induced by suggestion or hypnosis. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 204.

Pioneer dream researcher Montague Ullman (1988) states, "I no longer look upon dreaming primarily as an individual matter. Rather, I see it as an adaptation concerned with the survival of the species and only secondarily with the individual." Shamanic dreaming harnesses this transcultural aspect of dreamtime.

For Ullman, dreams represent our failures and frustrations in maintaining positive bonds, links to others, our connections with the larger supportive environment, our capacity for involvement. The images metaphorically reflect the core of our being, the place we have made for ourselves in the world. They offer deeper insight into the truth about ourselves, a way of exploring both internal and external hindrances to flow and unbroken wholeness. His view of dreams suggests, "that we are capable of looking deeply into the face of reality and of seeing mirrored in that face the most subtle and poignant features of our struggle to transcend our personal, limited, self-contained, autonomous selves so as to be able to connect with, and be part of, a larger unity." --Miller, Unborn Dream

The object of meditation is prescribed in the East but here we take a fragment of a dream or something of that kind and meditate upon it. ~Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 3, Page 15.

When you are in the darkness you take the next thing, and that is a dream.

And you can be sure that the dream is your nearest friend; the dream is the friend of those who are not guided any more by the traditional truth and in consequence are isolated.

~Carl Jung, The Symbolic Life, Para 674.

The dreams of early childhood contain mythological motifs which the children could not possibly know of. These archetypal images are the primeval knowledge of mankind; we are born with this inheritance, though this fact is not obvious and only becomes visible in indirect ways. ~Carl Jung, ETH, Lecture XIV, Page 119.

It is as if the dream were quite uninterested in the fate of the ego, it is pure Nature, it expresses the given thing, it mirrors the state of our consciousness with complete detachment; it never says "to do it in such and such a way would be well”, but states that it is so. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 8March1935, Pages 198.

Dreams as a whole are without purpose, like nature herself, it is wiser to regard them as such. The third question asks if we can dream of experiences undergone by our ancestors. I cannot be sure of this. There are so many curious sources from which we dream, that we cannot say for certain where anything comes from. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 8March1935, Pages 198.

Dreams can spring from physical or psychic causes, a dream can be caused by hunger, fever, cold, et cetera, but even then the dreams themselves are made of psychic material.

All dreams originate in the unconscious though occasionally a dream can be induced by suggestion or hypnosis. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 1May1935, Pages 202.

The essential thing is not what the dreamer believes but what he is;

it is not my creed that matters, but what I am, every gesture betrays me.

~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 199.

There are certain dreams which seem really to concern themselves with the fate of the ego, but these belong to the category of big dreams. Dreams as a whole are without purpose, like nature herself, it is wiser to regard them as such.

~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 198.

All dreams originate in the unconscious though occasionally a dream can be induced by suggestion or hypnosis. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 204.

Pioneer dream researcher Montague Ullman (1988) states, "I no longer look upon dreaming primarily as an individual matter. Rather, I see it as an adaptation concerned with the survival of the species and only secondarily with the individual." Shamanic dreaming harnesses this transcultural aspect of dreamtime.

For Ullman, dreams represent our failures and frustrations in maintaining positive bonds, links to others, our connections with the larger supportive environment, our capacity for involvement. The images metaphorically reflect the core of our being, the place we have made for ourselves in the world. They offer deeper insight into the truth about ourselves, a way of exploring both internal and external hindrances to flow and unbroken wholeness. His view of dreams suggests, "that we are capable of looking deeply into the face of reality and of seeing mirrored in that face the most subtle and poignant features of our struggle to transcend our personal, limited, self-contained, autonomous selves so as to be able to connect with, and be part of, a larger unity." --Miller, Unborn Dream

The object of meditation is prescribed in the East but here we take a fragment of a dream or something of that kind and meditate upon it. ~Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 3, Page 15.

When you are in the darkness you take the next thing, and that is a dream.

And you can be sure that the dream is your nearest friend; the dream is the friend of those who are not guided any more by the traditional truth and in consequence are isolated.

~Carl Jung, The Symbolic Life, Para 674.

The dreams of early childhood contain mythological motifs which the children could not possibly know of. These archetypal images are the primeval knowledge of mankind; we are born with this inheritance, though this fact is not obvious and only becomes visible in indirect ways. ~Carl Jung, ETH, Lecture XIV, Page 119.

It is as if the dream were quite uninterested in the fate of the ego, it is pure Nature, it expresses the given thing, it mirrors the state of our consciousness with complete detachment; it never says "to do it in such and such a way would be well”, but states that it is so. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 8March1935, Pages 198.

Dreams as a whole are without purpose, like nature herself, it is wiser to regard them as such. The third question asks if we can dream of experiences undergone by our ancestors. I cannot be sure of this. There are so many curious sources from which we dream, that we cannot say for certain where anything comes from. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 8March1935, Pages 198.

Dreams can spring from physical or psychic causes, a dream can be caused by hunger, fever, cold, et cetera, but even then the dreams themselves are made of psychic material.

All dreams originate in the unconscious though occasionally a dream can be induced by suggestion or hypnosis. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 1May1935, Pages 202.

BIG DREAMS

Big Dreams, also known as archetypal dreams, seem to be cut from a different cloth. Most importantly, they feel more real than real life, and a strong “felt meaning” is experienced in the moment. I think some visitation dreams definitely fit this description. But the other categories really set Big Dreams apart from ordinary dreams.

The most common elements are: encounters with mythological creatures and strange, intelligent animals feeling awe, fascination, fear and terror, and a sense of “Other”abstract geometric patterns and kaleidoscopic mandalas,the experience of flying, floating or falling,

Unlike ordinary dreams, these dreams are not easily picked at with standard dream interpretation procedures like psychoanalysis because very little personal history is encoded in these larger-than-life experiences. Archetypal dreams also have a consistency unmatched by ordinary dreams; in other words, their structure is cleanly focused, and the delivery to consciousness resembles waking visions of shamans and saints more than other nocturnal dreams.

For the Elgoni tribe of dreamers, big dreams were seen as collective dreams. The dreamer was dreaming for the community, for the landscape, and perhaps for all of the world. This shamanic style of dreaming matched well with Jung’s own experience, and it gave him further insight into his theories of the collective unconscious (as a side note, later in life, Jung revised his earlier essays about the collective unconscious and moved away from theories dealing with “racial memory”, instead framing these shared experiences in a way that is more parsimonious with today’s evolutionary psychology: as bodily expressions transformed metaphorically into cognitive symbols that all humans share due to our common biological heritage.)

http://dreamstudies.org/2008/11/14/big-dreams-archetypal-visions/

Big Dreams, also known as archetypal dreams, seem to be cut from a different cloth. Most importantly, they feel more real than real life, and a strong “felt meaning” is experienced in the moment. I think some visitation dreams definitely fit this description. But the other categories really set Big Dreams apart from ordinary dreams.

The most common elements are: encounters with mythological creatures and strange, intelligent animals feeling awe, fascination, fear and terror, and a sense of “Other”abstract geometric patterns and kaleidoscopic mandalas,the experience of flying, floating or falling,

Unlike ordinary dreams, these dreams are not easily picked at with standard dream interpretation procedures like psychoanalysis because very little personal history is encoded in these larger-than-life experiences. Archetypal dreams also have a consistency unmatched by ordinary dreams; in other words, their structure is cleanly focused, and the delivery to consciousness resembles waking visions of shamans and saints more than other nocturnal dreams.

For the Elgoni tribe of dreamers, big dreams were seen as collective dreams. The dreamer was dreaming for the community, for the landscape, and perhaps for all of the world. This shamanic style of dreaming matched well with Jung’s own experience, and it gave him further insight into his theories of the collective unconscious (as a side note, later in life, Jung revised his earlier essays about the collective unconscious and moved away from theories dealing with “racial memory”, instead framing these shared experiences in a way that is more parsimonious with today’s evolutionary psychology: as bodily expressions transformed metaphorically into cognitive symbols that all humans share due to our common biological heritage.)

http://dreamstudies.org/2008/11/14/big-dreams-archetypal-visions/

A dream gives us unadorned information about the condition of a patient, it is as if a nature- being were stating his diagnosis or taking a child by the ear and telling him what he is doing. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 18Jan1935, Page 174.

Dreams never really repeat experience, they always have a meaning, they are like association experiments, only they themselves produce the test words, they are a whole system of test words. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture XI 5July1934, Page 134.

Big dreams are impressive, they go with us through life, and sometimes change us through and through, but small dreams are fragmentary and just deal with the personal moment. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture XI 5July1934, Page 133.

So we cannot judge dreams from the conscious point of view, but can only think of them as complementary to consciousness. Dreams answer the questions of our conscious.

~Jung, ETH Lecture V 23Nov1934 Page 157.

It was the anticipatory quality in dreams that was first valued by antiquity and they played an important role in the ritual of many religions. ~Jung, ETH Lecture V 23Nov1934 P. 156.

Dreams often seem nonsense to us, but they spring from nature and are related to our future life. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture V 23Nov1934 Page 156.

A dream is a product of nature, the patient has not made it, it is like a letter dropped from Heaven, something which we know nothing of. ~ Jung, ETH Lecture V 23Nov1934 Page 156.

A dream gives us unadorned information about the condition of a patient, it is as if a nature- being were stating his diagnosis or taking a child by the ear and telling him what he is doing. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 18Jan1935, Page 174.

A symbol of primal source of growth and potential that can heal or destroy. In dreams they can appear as a magician, doctor, priest, father, teacher, guru or any other authority figure. Jung called this archetype 'mana' personalities. They can lead us to higher levels of awareness, or away from them. Trickster appears when a way of thinking becomes outmoded needs to be torn down built anew. He is the Destroyer of Worlds at the same time the savior of us all. In dreams {and myth} the trickster can be seen as The Fool The Magician The Clown The Jester The Villain The Destroyer. The shadow is often depicted as: A shadowy figure, often the same sex as dreamer but inferior; a zombie or walking dead; a dark shape; an unseen "Thing"; someone or something we feel uneasy about or in some measure repelled by; drug addict; pervert; what is behind one in a dream; anything dark or threatening; sometimes a younger brother or sister; a junior colleague; a foreigner; a servant; a gypsy; a prostitute; a burglar; a sinister figure in the dark. The shadow can appear in dreams or visions and may take a variety of forms. It might appear as a snake, a monster, a demon, a dragon or some other dark, wild or exotic figure.

Some symbols of the anima are the cow, a cat, a tiger, a cave and a ship. All of those are more or less female figures. Ships are associated with the sea, which is a common symbol for the feminine, and are womb-like insofar as they are hollow. (At a launching we still say, 'Bless all who sail her".) Caves are hollow and womb-like. Sometimes they are filled with water, which - as we have seen - is a symbol of the feminine, and are the womb of the Mother Earth or vaginal entrances to her womb. The earth is seen as female (Mother Earth) and symbolizes sensuous existence - that is, existence confined within the limits of the senses - plus intuition.

With the exception of the mother figure, the dream symbols representing soul-image are always of the opposite sex to the dreamer. Thus, a man's anima may be represented in his dreams by his sister; a woman's animus by her brother. Some other symbols of the animus are an eagle, a bull, a lion, and a phallus (erect penis) or other phallic figure such as a tower or spear. The eagle is associated with high altitudes and in mythology the sky is usually (ancient Egyptian mythology is the exception) regarded as a male and symbolizes pure reason or spirituality. In dreams the Divine Child usually appears as a baby or infant. It is both vulnerable, yet at the same time inviolate and possessing great transforming power. The persona can appear in dreams as a scarecrow or tramp, or as a desolate landscape, or as a social outcast. To be naked in a dream would symbolize a loss of persona.

Dreams never really repeat experience, they always have a meaning, they are like association experiments, only they themselves produce the test words, they are a whole system of test words. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture XI 5July1934, Page 134.

Big dreams are impressive, they go with us through life, and sometimes change us through and through, but small dreams are fragmentary and just deal with the personal moment. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture XI 5July1934, Page 133.

So we cannot judge dreams from the conscious point of view, but can only think of them as complementary to consciousness. Dreams answer the questions of our conscious.

~Jung, ETH Lecture V 23Nov1934 Page 157.

It was the anticipatory quality in dreams that was first valued by antiquity and they played an important role in the ritual of many religions. ~Jung, ETH Lecture V 23Nov1934 P. 156.

Dreams often seem nonsense to us, but they spring from nature and are related to our future life. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture V 23Nov1934 Page 156.

A dream is a product of nature, the patient has not made it, it is like a letter dropped from Heaven, something which we know nothing of. ~ Jung, ETH Lecture V 23Nov1934 Page 156.

A dream gives us unadorned information about the condition of a patient, it is as if a nature- being were stating his diagnosis or taking a child by the ear and telling him what he is doing. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 18Jan1935, Page 174.

A symbol of primal source of growth and potential that can heal or destroy. In dreams they can appear as a magician, doctor, priest, father, teacher, guru or any other authority figure. Jung called this archetype 'mana' personalities. They can lead us to higher levels of awareness, or away from them. Trickster appears when a way of thinking becomes outmoded needs to be torn down built anew. He is the Destroyer of Worlds at the same time the savior of us all. In dreams {and myth} the trickster can be seen as The Fool The Magician The Clown The Jester The Villain The Destroyer. The shadow is often depicted as: A shadowy figure, often the same sex as dreamer but inferior; a zombie or walking dead; a dark shape; an unseen "Thing"; someone or something we feel uneasy about or in some measure repelled by; drug addict; pervert; what is behind one in a dream; anything dark or threatening; sometimes a younger brother or sister; a junior colleague; a foreigner; a servant; a gypsy; a prostitute; a burglar; a sinister figure in the dark. The shadow can appear in dreams or visions and may take a variety of forms. It might appear as a snake, a monster, a demon, a dragon or some other dark, wild or exotic figure.

Some symbols of the anima are the cow, a cat, a tiger, a cave and a ship. All of those are more or less female figures. Ships are associated with the sea, which is a common symbol for the feminine, and are womb-like insofar as they are hollow. (At a launching we still say, 'Bless all who sail her".) Caves are hollow and womb-like. Sometimes they are filled with water, which - as we have seen - is a symbol of the feminine, and are the womb of the Mother Earth or vaginal entrances to her womb. The earth is seen as female (Mother Earth) and symbolizes sensuous existence - that is, existence confined within the limits of the senses - plus intuition.

With the exception of the mother figure, the dream symbols representing soul-image are always of the opposite sex to the dreamer. Thus, a man's anima may be represented in his dreams by his sister; a woman's animus by her brother. Some other symbols of the animus are an eagle, a bull, a lion, and a phallus (erect penis) or other phallic figure such as a tower or spear. The eagle is associated with high altitudes and in mythology the sky is usually (ancient Egyptian mythology is the exception) regarded as a male and symbolizes pure reason or spirituality. In dreams the Divine Child usually appears as a baby or infant. It is both vulnerable, yet at the same time inviolate and possessing great transforming power. The persona can appear in dreams as a scarecrow or tramp, or as a desolate landscape, or as a social outcast. To be naked in a dream would symbolize a loss of persona.

Archetypal Approach

The basic philosophy behind archetypal psychology was inspired by Carl Jung’s concept of the archetypes: Primordial symbols, appearing predominantly within our dreams, which are the common heritage of all mankind. The concept of archetypes implies that there are sources of health, healing, strength and wisdom within the psyche that are accessible to all of us. Archetypal psychology seeks to open up connections to this deeper source, believing that the true cures for a wide array of mental and emotional problems can be found there.

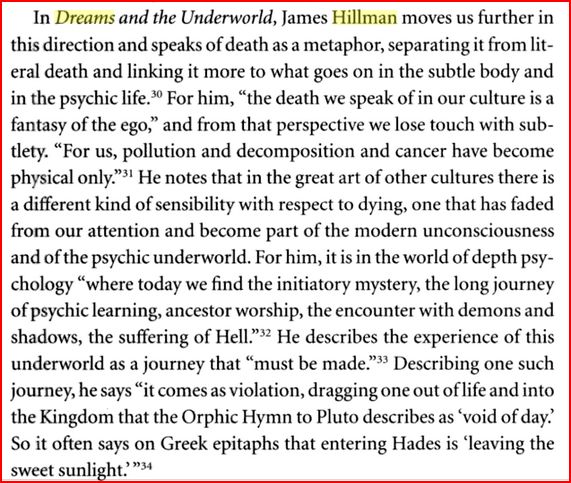

In The Dream and the Underworld, archetypal psychologist and post-Jungian James Hillman prefers to allow the dream and dream symbols to remain what they are, and not to analyze and interpret them but to simply interact with them and see what comes about. However, Hillman’s method of seeing focuses far more on an artistic view than from a therapeutic or results-oriented standpoint. As such, when it comes to dreams and symbols, he stays with the process and activity itself instead of seeking an outcome or solution. He values the description over interpretation, the animating and making a thing come alive rather than suffocating it with a contrived explanation from outside the dream. He thrives on visiting the dream in its own realm of power, the underworld, and in honoring it by allowing it to be its own entity there instead of trying to make it come alive in our ordinary world of thinking.

Hillman’s goal, as was Jung’s, is to get ever closer to the characters and activity in the dream realm, but as opposed to Jung who then turned to amplification in order to find meaning and interpretation at the level of the waking ego, Hillman chooses not to bring the dream element back into waking life and force it to match up with symbols or meanings we already hold. In fact, Hillman claims that to bring the dream out of the underworld actually betrays the dream. Hillman advocates finding wordplays, asking questions of the objects themselves, and then allowing them to live out their own soul-like existence without comparison or contrast to external references. He chides us in our desire to analyze, our wish to know, and speaks of “letting our desire die away into its images (p. 201). http://www.depthinsights.com/blog/working-with-dreams-depth-psychology-techniques-of-carl-gustav-jung-and-james-hillman/#sthash.nTyRGyAb.dpuf

Jung studied how historical religions, deities, and fables influenced an individual’s sense of self. Archetypal psychology theorizes that a person’s dreams and psyche are intertwined with their beliefs and that this union is what forms their behaviors, thoughts, and emotions. The archetype is symbolic of an individual’s collective life experiences and determines what choices, both conscious and unconscious, a person makes. Archetypal psychology focuses on the soul of a person and Jung and his predecessors found similarities in the archetypes of legends and the drive that is human motivation. Today, archetypal psychologists still consider archetypes a prominent force in the development of an individual’s psychological construct.

Dream analysis

Because Hillman's archetypal psychology is concerned with fantasy, myth, and image, it is not surprising that dreams are considered to be significant in relation to soul and soul-making. Hillman does not believe that dreams are simply random residue or flotsam from waking life (as advanced by physiologists), but neither does he believe that dreams are compensatory for the struggles of waking life, or are invested with “secret” meanings of how one should live (à la Jung). Rather, “dreams tell us where we are, not what to do” (1979). Therefore, Hillman is against the 20th century traditional interpretive methods of dream analysis. Hillman’s approach is phenomenological rather than analytic (which breaks the dream down into its constituent parts) and interpretive/hermeneutic (which may make a dream image “something other” than what it appears to be in the dream). His dictum with regard to dream content and process is “Stick with the image.”

Hillman (1983) describes his position succinctly:

For instance, a black snake comes in a dream, a great big black snake, and you can spend a whole hour with this black snake talking about the devouring mother, talking about anxiety, talking about the repressed sexuality, talking about the natural mind, all those interpretive moves that people make, and what is left, what is vitally important, is what this snake is doing, this crawling huge black snake that’s walking into your life…and the moment you’ve defined the snake, you’ve interpreted it, you’ve lost the snake, you’ve stopped it.… The task of analysis is to keep the snake there.… The snake in the dream does not become something else: it is none of the things Hillman mentioned, and neither is it a penis, as Hillman says Freud might have maintained, nor the serpent from the Garden of Eden, as Hillman thinks Jung might have mentioned. It is not something someone can look up in a dream dictionary; its meaning has not been given in advance. Rather, the black snake is the black snake. Approaching the dream snake phenomenologically simply means describing the snake and attending to how the snake appears as a snake in the dream. It is a huge black snake, that is given. But are there other snakes in the dream? If so, is it bigger than the other snakes? Smaller? Is it a black snake among green snakes? Or is it alone? What is the setting, a desert or a rain forest? Is the snake getting ready to feed? Shedding its skin? Sunning itself on a rock? All of these questions are elicited from the primary image of the snake in the dream, and as such can be rich material revealing the psychological life of the dreamer and the life of the psyche spoken through the dream. [Wikipedia - Hillman]

The basic philosophy behind archetypal psychology was inspired by Carl Jung’s concept of the archetypes: Primordial symbols, appearing predominantly within our dreams, which are the common heritage of all mankind. The concept of archetypes implies that there are sources of health, healing, strength and wisdom within the psyche that are accessible to all of us. Archetypal psychology seeks to open up connections to this deeper source, believing that the true cures for a wide array of mental and emotional problems can be found there.

In The Dream and the Underworld, archetypal psychologist and post-Jungian James Hillman prefers to allow the dream and dream symbols to remain what they are, and not to analyze and interpret them but to simply interact with them and see what comes about. However, Hillman’s method of seeing focuses far more on an artistic view than from a therapeutic or results-oriented standpoint. As such, when it comes to dreams and symbols, he stays with the process and activity itself instead of seeking an outcome or solution. He values the description over interpretation, the animating and making a thing come alive rather than suffocating it with a contrived explanation from outside the dream. He thrives on visiting the dream in its own realm of power, the underworld, and in honoring it by allowing it to be its own entity there instead of trying to make it come alive in our ordinary world of thinking.

Hillman’s goal, as was Jung’s, is to get ever closer to the characters and activity in the dream realm, but as opposed to Jung who then turned to amplification in order to find meaning and interpretation at the level of the waking ego, Hillman chooses not to bring the dream element back into waking life and force it to match up with symbols or meanings we already hold. In fact, Hillman claims that to bring the dream out of the underworld actually betrays the dream. Hillman advocates finding wordplays, asking questions of the objects themselves, and then allowing them to live out their own soul-like existence without comparison or contrast to external references. He chides us in our desire to analyze, our wish to know, and speaks of “letting our desire die away into its images (p. 201). http://www.depthinsights.com/blog/working-with-dreams-depth-psychology-techniques-of-carl-gustav-jung-and-james-hillman/#sthash.nTyRGyAb.dpuf

Jung studied how historical religions, deities, and fables influenced an individual’s sense of self. Archetypal psychology theorizes that a person’s dreams and psyche are intertwined with their beliefs and that this union is what forms their behaviors, thoughts, and emotions. The archetype is symbolic of an individual’s collective life experiences and determines what choices, both conscious and unconscious, a person makes. Archetypal psychology focuses on the soul of a person and Jung and his predecessors found similarities in the archetypes of legends and the drive that is human motivation. Today, archetypal psychologists still consider archetypes a prominent force in the development of an individual’s psychological construct.

Dream analysis

Because Hillman's archetypal psychology is concerned with fantasy, myth, and image, it is not surprising that dreams are considered to be significant in relation to soul and soul-making. Hillman does not believe that dreams are simply random residue or flotsam from waking life (as advanced by physiologists), but neither does he believe that dreams are compensatory for the struggles of waking life, or are invested with “secret” meanings of how one should live (à la Jung). Rather, “dreams tell us where we are, not what to do” (1979). Therefore, Hillman is against the 20th century traditional interpretive methods of dream analysis. Hillman’s approach is phenomenological rather than analytic (which breaks the dream down into its constituent parts) and interpretive/hermeneutic (which may make a dream image “something other” than what it appears to be in the dream). His dictum with regard to dream content and process is “Stick with the image.”

Hillman (1983) describes his position succinctly:

For instance, a black snake comes in a dream, a great big black snake, and you can spend a whole hour with this black snake talking about the devouring mother, talking about anxiety, talking about the repressed sexuality, talking about the natural mind, all those interpretive moves that people make, and what is left, what is vitally important, is what this snake is doing, this crawling huge black snake that’s walking into your life…and the moment you’ve defined the snake, you’ve interpreted it, you’ve lost the snake, you’ve stopped it.… The task of analysis is to keep the snake there.… The snake in the dream does not become something else: it is none of the things Hillman mentioned, and neither is it a penis, as Hillman says Freud might have maintained, nor the serpent from the Garden of Eden, as Hillman thinks Jung might have mentioned. It is not something someone can look up in a dream dictionary; its meaning has not been given in advance. Rather, the black snake is the black snake. Approaching the dream snake phenomenologically simply means describing the snake and attending to how the snake appears as a snake in the dream. It is a huge black snake, that is given. But are there other snakes in the dream? If so, is it bigger than the other snakes? Smaller? Is it a black snake among green snakes? Or is it alone? What is the setting, a desert or a rain forest? Is the snake getting ready to feed? Shedding its skin? Sunning itself on a rock? All of these questions are elicited from the primary image of the snake in the dream, and as such can be rich material revealing the psychological life of the dreamer and the life of the psyche spoken through the dream. [Wikipedia - Hillman]

Ancestral Vigal; Dream Incubation

The dream is its own interpretation.

“The dream is the small hidden door in the deepest and most intimate sanctum of the soul, which opens into that primeval cosmic night that was soul long before there was a conscious ego and will be soul far beyond what a conscious ego could ever reach.” —Jung, The Meaning of Psychology for Modern Man, 1934

This whole creation is essentially subjective, and the dream is the theater where the dreamer is at once scene, actor, prompter, stage manager, author, audience, and critic.

--General Aspects of Dream Psychology (1928)

It has been proved over and over again that very long dreams can take place in the

shortest time imaginable. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 40.

There are people who hold that dreams are self sufficient and that they can be understood without their associations. This is an illusion. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 142.

There is no stereotyped explanation for dream symbols, we must not forget that words often have a totally different setting for other people than for ourselves and if we talk to them from our preconceived ideas it is as bad as talking Swiss-German to an Englishman. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 141.

It is as if there were another time, under the dream, and as if something existed there which knew far more and saw much further than we do. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 134.

The psychic contents of a dream are very complicated; it runs timelessly through the head as if there were no time. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 134.

The position of the body produces some dreams, and a real noise can work itself into a dream in a most peculiar way. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 134.

With complexes we are still in a sphere where we can experiment, but with dreams experimenting comes to an end, for we are dealing with pure nature. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 133.

“This is the secret of dreams—that we do not dream, but rather we are dreamt.”

Professor Jung:

This is the secret of dreams—that we do not dream, but rather we are dreamt.

We are the object of the dream, not its maker.

The French say: “To makedream.”

This is wrong.

The dream is dreamed to us.

We are the objects.

We simply find ourselves put into a situation.

If a fatal destiny is awaiting us, we are already seized by what will lead us to this destiny in the dream, in the same way it will overcome us in reality.

One of my friends, who was attacked by a mamba (cobra) in Africa, dreamed of this event two months in advance in Zurich.

The snake attacked him in the dream exactly in the way it later did in reality.

Such a dream is anticipated fate.

Participant:

So we cannot always assume that the dream wants to make something conscious?

Professor Jung:

No, not at all.

This is anthropomorphic thinking.

We can only try to understand what the dream offers.

If we are wise, we can put it to use.

We must not think that dreams necessarily have a benevolent intention.

Nature is kind and generous, but also absolutely cruel.

That is its characteristic.

Think of children.

There is nothing more cruel than children, and yet they are so lovely.

If I had such a dream, I would naturally react differently from the woman in question.

But as I am a different person, I also have a different dream.

So that’s not how we should think. We can only compare.

The hopeless case has the hopeless dream, the hopeful one has the hopeful dream.

Participant:

Is it possible to understand all dreams? Isn’t it already in the nature of such a dream that it cannot be understood?

Professor Jung:

If the dreamer had had it in her to understand this dream at some point later on, there probably would have been a suffix of hope added to it.

There would be a ray of light at the end, which would give the doctor a hint.

He could then say: “You have had a very alarming dream.”

And the patient would perhaps understand him. If she understands the dream, she will be on her way to integrate the pathological part.

With this patient, I had talked about dreams. Interestingly, she did not mention these dreams.

But when she was gone, they came to her as an esprit d’escalier.

She then told me about them in a letter.

If the dreamer had actually told them, I would have been even more scared.

I had seen her a couple of times, but had not come far enough to identify the content of her peculiar disturbance.

She did not come into a mental institution, but hovers above the ground as a shadow.

Right before she came to me, she had undergone a psychotic phase.

She came to me during the downhill phase of a psychotic interval.

You can see which fate the two dreams from childhood have anticipated.

Participant: Couldn’t there come positive dreams again later on, which would lessen the uncanny aspect?

Professor Jung:

Positive dreams may well follow, but none of them have the importance of the childhood dreams, because the child is much nearer the collective unconscious than the adults.

Children still live directly in the great images.

There are high points in life—puberty, midlife—when the great dreams appear again, those dreamed out of the depth of the personality.

In the life of the adult, dreams mostly refer to personal life.

Then the persona is in the foreground, what is essential in their personality has long emigrated, is long gone, perhaps never to be reached again. ~Children’s Dreams Seminar, Pages 159-160.

We are not far from the truth, in fact we are very near to primeval truth, when we think of our dreams as answers to questions, which we have asked and which we have not asked. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 2, Page 157

Dreams repeat themselves and motifs appear again and again, sometimes quite regularly, showing the continuity of the unconscious processes. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 2, Page 167

A single dream is not convincing, one dream flows out of another, they are images which come from an inner source, a stream that never ceases and which comes to the surface when our consciousness relaxes. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 2, Pages 166-167.

Phantasies and dreams do not of themselves enlarge consciousness, they have to be understood and here the great difficulty begins. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture III, 17May 1935, Pages 208.

Speaking from the standpoint of many thousands of dreams I cannot say that they show guidance. It is as if the dream were quite uninterested in the fate of the ego, it is pure Nature, it expresses the given thing, it mirrors the state of our consciousness with complete detachment; it never says "to do it in such and such a way would be well", but states that it is so. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 198.

The dream is its own interpretation.

“The dream is the small hidden door in the deepest and most intimate sanctum of the soul, which opens into that primeval cosmic night that was soul long before there was a conscious ego and will be soul far beyond what a conscious ego could ever reach.” —Jung, The Meaning of Psychology for Modern Man, 1934

This whole creation is essentially subjective, and the dream is the theater where the dreamer is at once scene, actor, prompter, stage manager, author, audience, and critic.

--General Aspects of Dream Psychology (1928)

It has been proved over and over again that very long dreams can take place in the

shortest time imaginable. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 40.

There are people who hold that dreams are self sufficient and that they can be understood without their associations. This is an illusion. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 142.

There is no stereotyped explanation for dream symbols, we must not forget that words often have a totally different setting for other people than for ourselves and if we talk to them from our preconceived ideas it is as bad as talking Swiss-German to an Englishman. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 141.

It is as if there were another time, under the dream, and as if something existed there which knew far more and saw much further than we do. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 134.

The psychic contents of a dream are very complicated; it runs timelessly through the head as if there were no time. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 134.

The position of the body produces some dreams, and a real noise can work itself into a dream in a most peculiar way. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 134.

With complexes we are still in a sphere where we can experiment, but with dreams experimenting comes to an end, for we are dealing with pure nature. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 1, Page 133.

“This is the secret of dreams—that we do not dream, but rather we are dreamt.”

Professor Jung:

This is the secret of dreams—that we do not dream, but rather we are dreamt.

We are the object of the dream, not its maker.

The French say: “To makedream.”

This is wrong.

The dream is dreamed to us.

We are the objects.

We simply find ourselves put into a situation.

If a fatal destiny is awaiting us, we are already seized by what will lead us to this destiny in the dream, in the same way it will overcome us in reality.

One of my friends, who was attacked by a mamba (cobra) in Africa, dreamed of this event two months in advance in Zurich.

The snake attacked him in the dream exactly in the way it later did in reality.

Such a dream is anticipated fate.

Participant:

So we cannot always assume that the dream wants to make something conscious?

Professor Jung:

No, not at all.

This is anthropomorphic thinking.

We can only try to understand what the dream offers.

If we are wise, we can put it to use.

We must not think that dreams necessarily have a benevolent intention.

Nature is kind and generous, but also absolutely cruel.

That is its characteristic.

Think of children.

There is nothing more cruel than children, and yet they are so lovely.

If I had such a dream, I would naturally react differently from the woman in question.

But as I am a different person, I also have a different dream.

So that’s not how we should think. We can only compare.

The hopeless case has the hopeless dream, the hopeful one has the hopeful dream.

Participant:

Is it possible to understand all dreams? Isn’t it already in the nature of such a dream that it cannot be understood?

Professor Jung:

If the dreamer had had it in her to understand this dream at some point later on, there probably would have been a suffix of hope added to it.

There would be a ray of light at the end, which would give the doctor a hint.

He could then say: “You have had a very alarming dream.”

And the patient would perhaps understand him. If she understands the dream, she will be on her way to integrate the pathological part.

With this patient, I had talked about dreams. Interestingly, she did not mention these dreams.

But when she was gone, they came to her as an esprit d’escalier.

She then told me about them in a letter.

If the dreamer had actually told them, I would have been even more scared.

I had seen her a couple of times, but had not come far enough to identify the content of her peculiar disturbance.

She did not come into a mental institution, but hovers above the ground as a shadow.

Right before she came to me, she had undergone a psychotic phase.

She came to me during the downhill phase of a psychotic interval.

You can see which fate the two dreams from childhood have anticipated.

Participant: Couldn’t there come positive dreams again later on, which would lessen the uncanny aspect?

Professor Jung:

Positive dreams may well follow, but none of them have the importance of the childhood dreams, because the child is much nearer the collective unconscious than the adults.

Children still live directly in the great images.

There are high points in life—puberty, midlife—when the great dreams appear again, those dreamed out of the depth of the personality.

In the life of the adult, dreams mostly refer to personal life.

Then the persona is in the foreground, what is essential in their personality has long emigrated, is long gone, perhaps never to be reached again. ~Children’s Dreams Seminar, Pages 159-160.

We are not far from the truth, in fact we are very near to primeval truth, when we think of our dreams as answers to questions, which we have asked and which we have not asked. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 2, Page 157

Dreams repeat themselves and motifs appear again and again, sometimes quite regularly, showing the continuity of the unconscious processes. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 2, Page 167

A single dream is not convincing, one dream flows out of another, they are images which come from an inner source, a stream that never ceases and which comes to the surface when our consciousness relaxes. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 2, Pages 166-167.

Phantasies and dreams do not of themselves enlarge consciousness, they have to be understood and here the great difficulty begins. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture III, 17May 1935, Pages 208.

Speaking from the standpoint of many thousands of dreams I cannot say that they show guidance. It is as if the dream were quite uninterested in the fate of the ego, it is pure Nature, it expresses the given thing, it mirrors the state of our consciousness with complete detachment; it never says "to do it in such and such a way would be well", but states that it is so. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 198.

The dream is never a mere repetition of previous experiences, with only one specific exception: shock or shell shock dreams, which sometimes are completely identical repetitions of reality. That, in fact, is a proof of the traumatic effect. ~Carl Jung, Children’s Dream Seminar, Page 21.

And if we happen to have a precognitive dream, how can we possibly ascribe it to our own powers? ~Carl Jung, Memories Dreams and Reflections, Page 340.

The Ancestral Core

The chief concern of the Red Book (Jung's Book of the Dead), according to Hillman and Shamdasani, is giving voice to the dead - to history, to the actual dead, to buried ideas. Our culture is so forward looking, valuing novelty over reflection on the past, that the ancestors are too often forgotten. If we don't deal with them, their lament will continue to haunt us and foil our intents. True novelty requires the seed-bed of the past's rich loam.

Dreams and fantasies play significant roles in waking life. In addition, a major focus is “the dead” as both a literal and metaphysical concept, as well as the imperative to provide a voice and place for the dead to enable our own living.

Jung calls attention to the one deep, missing part of our culture, which is the realm of the dead. The realm not just of your personal ancestors but the realm of the dead, the weight of human history, and what is the real repressed, and that is like a great monster eating us from within and from below and sapping our strength as a culture. It's all that's forgotten, and not just forgotten in the past, but that we're living in a world which is alive with the dead, they’re around us, they're with us, they are us. The figures, the memories, the ghosts, it's all there, and as you get older your borders dissolve, and you realize I am among them.

--Lament of the Dead

We have to place the dream so that we can see it in human life, we have to see its meaning in the psyche. A dream comes in a fragmentary form like a telegram and we often fail to understand it for want of context. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 2, Page 166.

Precognitive dreams can be recognized and verified as such only when the precognized event has actually happened.

Otherwise the greatest uncertainty prevails.

Also, such dreams are relatively rare.

It is therefore not worth looking at the dreams for their future significance.

One usually gets it wrong. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Page 460-461.

And if we happen to have a precognitive dream, how can we possibly ascribe it to our own powers? ~Carl Jung, Memories Dreams and Reflections, Page 340.

The Ancestral Core

The chief concern of the Red Book (Jung's Book of the Dead), according to Hillman and Shamdasani, is giving voice to the dead - to history, to the actual dead, to buried ideas. Our culture is so forward looking, valuing novelty over reflection on the past, that the ancestors are too often forgotten. If we don't deal with them, their lament will continue to haunt us and foil our intents. True novelty requires the seed-bed of the past's rich loam.

Dreams and fantasies play significant roles in waking life. In addition, a major focus is “the dead” as both a literal and metaphysical concept, as well as the imperative to provide a voice and place for the dead to enable our own living.

Jung calls attention to the one deep, missing part of our culture, which is the realm of the dead. The realm not just of your personal ancestors but the realm of the dead, the weight of human history, and what is the real repressed, and that is like a great monster eating us from within and from below and sapping our strength as a culture. It's all that's forgotten, and not just forgotten in the past, but that we're living in a world which is alive with the dead, they’re around us, they're with us, they are us. The figures, the memories, the ghosts, it's all there, and as you get older your borders dissolve, and you realize I am among them.

--Lament of the Dead

We have to place the dream so that we can see it in human life, we have to see its meaning in the psyche. A dream comes in a fragmentary form like a telegram and we often fail to understand it for want of context. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 2, Page 166.

Precognitive dreams can be recognized and verified as such only when the precognized event has actually happened.

Otherwise the greatest uncertainty prevails.

Also, such dreams are relatively rare.

It is therefore not worth looking at the dreams for their future significance.

One usually gets it wrong. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Page 460-461.

The Value of Dreamwork,

by Iona Miller

The archetypes to be discovered and assimilated are precisely those which have inspired the basic images of ritual and mythology. These eternal ones of the dream are not to be confused with the personality modified symbolic figures that appear in nightmares or madness to the tormented individual. Dream is the personalized myth. Myth is the depersonalized dream. --Joseph Campbell

No one who does not know himself can know others. And in each of us there is another whom we do not know. He speaks to us in dream and tells us how differently he sees us from the way we see ourselves. When, therefore, we find ourselves in a different situation to which there is no solution, he can sometimes kindle a light that radically alters our attitude; the very attitude that led us into the difficult situation. --C. G. Jung

As we spend a large proportion of our lives in a dream state, a fuller understanding of their implications may prove valuable. Today, there are several prevailing theories concerning the significance and value of dreams. No final statement about dream may be made. There are several approaches to each perspective which is assumed a priori. There are many alternatives to choose from. One's choice of style in dreamwork will be determined by the mythemes currently embraced. The characteristic attitudes associated with the archetypes will motivate and influence one's approach to the dreamworld.

Strephon Kaplan Williams (3) (Jungian-Senoi Institute) is one of the foremost proponents of Dreamwork. He outlines a six-point program for continued use. 1. Dialogue with the dream characters, asking questions and recording answers. 2. Re-experience of the dream through imagination, art projects, and creativity. 3. Examination of unresolved aspects of the dream, and contemplation of solutions. 4. Actualization of insights in daily life, where relevant. 5. Meditation on the source of dreams and insight from the Self. 6. Synthesize the essence of dreamlife and its meaning in a journal and apply them in one's life journey. To offer a variety of other approaches, we will cover theories on dreams and dreaming from Jung's original work, the analytical psychology school, para-psychology, and archetypal or imaginal psychology.

Knowledge of the antiquated Freudian system is so wide-spread that no further comment here seems necessary. Jung was the first to depart from Freud's "sexuality-fraught" perception of dreams. Where Freud saw one complex, Jung saw many. He saw in dreams a gamut of archetypes overseen by the transcendent function, or Self. Analytical psychology amplified and clarified his original material. Most of this work is concerned with the fantasy of the process of individuation. It reflects an ego with a heroic attitude, and proceeds by stages of development. Consciousness, at this stage, is generally monotheistic. It has a tendency to seek the center of meaning, as if there were only One.

Parapsychological work done with dreams also seems to reflect this attitude of searching, influencing, and controlling. In Re-Visioning Psychology, James Hillman differs from the traditional analytical viewpoint by stating: Dreams are important to the Soul--not for the message the ego takes from them, not for the recovered memories or the revelations; what does seem to matter to the soul is the nightly encounter with a plurality of shades in an underworld...the freeing of the soul from its identity with the ego and the waking state...What we learn from dreams is what psychic nature really is--the nature of psychic reality; not I, but we...not monotheistic consciousness looking down from its mountain, but polytheistic consciousness wandering all over the place. In Jung's model, one major function of dreams is to provide the unconscious with a means of exercising its regulative activity. Conscious attitudes tend to become one-sided. Through their postulated compensatory effect, dreams present different data and varying points of view. Individuation is the psyche's goal; it seeks to bring this about through an internal adjustment procedure. There is an admonition in Magick to "balance each thought against its opposite."

Dreams, according to Jung, do this for us automatically. However, there must be a conscious striving toward incorporation of the balancing attitudes presented through dreams (this applies equally to fantasies and visions). Another apparent function for a dream state is to take old information, contained in long-term memory, incorporate it with those experiences, and integrate them with new experiences. This creates new attitudes. Since the dream conjoins current and past experiences to form new attitudes, the dream contains possible information about the future. There is a causal relationship between our attitudes and the events which manifest from our many possible futures. In studies at Maimonides Dream Labs, Stanley Krippner and Montague Ullman were trying to impress certain information on an individual's dream. They found that an individual, being monitored for dream states, could incorporate a mandala, which was being concentrated on by another subject, into his dream. This led to their famous theory on dream telepathy.

Dream symbols appear to allow repressed impulses to be expressed in disguised forms. Dream symbols are essential message-carriers from the instinctive-archetypal continuum to the rational part of the human mind. Their incorporation enriches consciousness, so that it learns to understand the forgotten language of the pre-conscious mind. The dream language presents symbols from which you can gain value through dream monitoring. You can use these dream symbols directly to facilitate communication with this other aspect of yourself.

Should you choose later to re-program yourself out of old habit patterns, you're going to want an accurate conception of what dream symbols really mean. A symbol always stands for something that is unknown. It contains more than it's obvious or immediate meaning. The symbolic function bridges man's inner and outer world. Symbolism represents a continuity of consciousness and preconscious mental activity, in which the preconscious extends beyond the boundaries of the individual. These primitive processes of prelogical thinking continue throughout life and do not indicate a regressive mode of thought.

Dream symbols are independent of time, space, and causality. The meaning of unconscious contents varies with the specific internal and external situation of the dreamer. Some dreams originate in a personal or conscious context. These dreams usually reflect personal conflicts, or fragmentary impressions left over from the day. Some dreams, on the other hand, are rooted in the contents of the collective unconscious. Their appearance is spontaneous and may be due to some conscious experience, which causes specific archetypes to constellate. It is often difficult to distinguish personal contents from collective contents. In dreams, archetypes often appear in contemporary dress, often as persons vitally connected with us.

In this case, both their personal aspect (or objective level), and their significance as projections or partial aspects of the psyche (subjective level) may be brought into consciousness. A dream is never merely a repetition of preceding events, except in the case of past psychic trauma. There is specific value in the symbols and context the psyche utilizes. It may produce any; why is it sending just this dream and not another?

Dreams rich in pictorial detail usually relate to individual problems. Universal contexts are revealed in simple, vivid images with scant detail. No attempt to interpret a single dream, or even the sequence dreams fall in, is fruitful. In fact, later research by Asklepia Foundation researchers asserts it is more important to journey using dreams as experiential springboards for therapeutic outcomes. In interpreting a group of dreams, we seek to discover the 'center of meaning' which all the dreams express in varied form.

When this 'center' is discovered by consciousness and its lesson assimilated, the dreams begin to spring from a new center. Recurring dreams generally indicate an unresolved conflict trying to break into consciousness. There are three types of significance a dream may carry: 1) It may stem from a definite impression of the immediate past. As a reaction, it supplements or compliments the impressions of the day. 2) Here there is balance between the conscious and unconsciousness components. The dream contents are independent of the conscious situation, and are so different from it they present conflict. 3) When this contrary position of the unconscious is stronger, we have spontaneous dreams with no relation to consciousness. These dreams are archetypal in origin, and consequently are over-powering, strange and often oracular. (These dreams are not necessarily most desirable to the student, as they may be extremely dangerous if the dreamer's ego is still too narrow to recognize and assimilate their meaning.)

We can never empirically determine the meaning of a dream. We cannot accept a meaning merely because it fits in with what we expected. Dreams can exert a reductive as well as prospective function. In other words, if our conscious attitude is inflated, dreams may compensate negatively, and show us our human frailty and dependence. They also may act positively by providing a 'guiding image' which corrects a self-devaluing attitude, re-establishing balance. The unconscious, by anticipating future conscious achievements, provides a rough plan for progress. Each life, says Jung, is guided by a private myth.

Each individual has a great store of DNA information. It is generally mediated by the archetypes which are deployed by both myth and dream. As you create this individual or private myth, it attracts, if you will, an archetypal pattern and molds itself in a characteristic way (or visa versa). The archetype precipitates compulsive action. It is the motivating factor which may become externalized in the physical world. Jung notes: "The dreamer's unconscious is communicating with the dreamer alone. And is selecting symbols which have meaning to the dreamer and no one else. They also involve the collective unconscious whose expression may be social rather than personal."

We may discover hidden meaning in our dreams and fantasies through the following procedure: 1) Determine the present situation of consciousness. What significant events surround the dream? 2) With the lowering of the threshold of consciousness, unconscious contents arise through dream, vision, and fantasy. 3) After perceiving the contents, record them so they are not lost (the Hermetic seal). 4) Investigate, clarify, and elaborate by amplification with personal meanings, and collective meaning, gleaned from similar motifs in myth and fairy tale. 5) Integrate this meaning with your general psychic situation. INstincts are the best guide; if you are obtaining "value" from your interpretation, it will "feel" correct. Complexes and their attendant archetypes draw attention to themselves but are difficult to pinpoint.